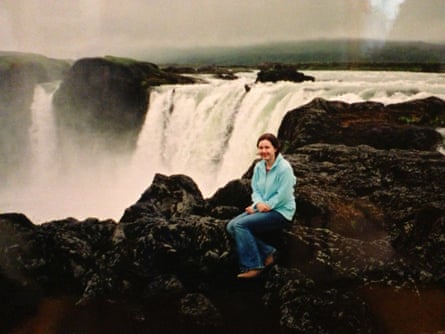

Lying in my bed, I listened to what sounded like a woman screaming outside in the dark. I picked up my pen. A month of living in this Icelandic village and I was still unaccustomed to the impenetrable January gloom and the ferocity of the wind; its propensity to sound sentient. I had started to feel like the island was trying to tell me something, had a story it wanted me to write.

Sauðárkrókur, a fishing town in the northern fjord of Skagafjörður, was all mountain, sea and valley. There were no trees to slow the Arctic winds, and I had already been blown sideways into a snowbank while walking home from Fjölbrautaskóli Norðurlands vestra, my new high school whose name I could not yet pronounce. At night, my dreams were filled with a soundscape of weeping women. When I woke, their wailing continued in the gusts outside. That was when I wrote. I wrote to understand myself in this new place. I wrote to understand Iceland, its brutality and its beauty.

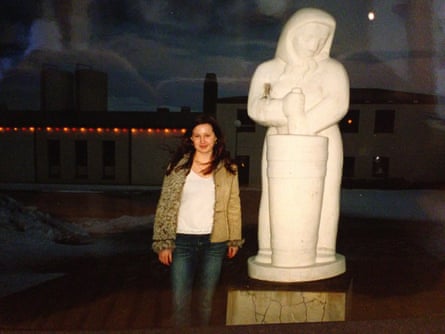

Photograph: Hannah Kent

When I applied for a foreign student exchange at 16, I did not give much thought to where I would like to live. It was enough to have a year of respite from the pressure to decide what to do with my life. Since I was six years old, I had wanted to write, needed to write as one needs to breathe, but, influenced by wider social rhetoric regarding the arts, I had come to believe that writing wasn’t serious or worthy. Yet the thought of shackling myself to some other acceptable profession by way of university applications filled me with dread, and when the local Rotary club announced it would sponsor a student for a year abroad, I saw the opportunity as a lifeline. With no language studies under my belt, I was told that a host country would be selected for me based on “my personality”. When I received a letter informing me that I would be sent to Iceland, I was surprised. I knew nothing of this small Nordic island of 250,000 people. I wondered what we would have in common.

By March, the winter winds had eased and the days lengthened into exquisite blue twilights. I was still overwhelmed by the difficulty of attending school, my unbelonging clear in the ongoing incomprehension and the stares that came my way, but writing about what I saw – the ravens circling, the fjord mirroring the height of the mountains – allowed me to step outside of my loneliness. Each night, in the privacy of my bedroom, I let the words pour from me.

One day, in Icelandic class, I started writing a poem in the margins of my notebook. Outside, I could see Mount Tindastóll, its snowy heights lit in pink from the late sunrise. I soon became so absorbed in pressing its beauty into paper that I did not notice my teacher, Geirlaugur, standing in front of me until he cleared his throat.

“What is so important that it stops you from working?” he asked me, tapping the neglected exercises. He peered down at my notebook, reading sideways. “Poetry?”

“Fyrirgefðu,” I said. Sorry.

The next day, when I returned to Icelandic class, Geirlaugur summoned me to his desk. I was expecting a reprimand, but instead he handed me an anthology of Icelandic nature poems, translated into English. He had included an inscription: To Hannah, From one poet to another, Geirlaugur.

“Keep going, and you will be published one day,” he told me. I was struck by his seriousness, the absence of any condescension.

“I hope so,” I replied.

He shook his head. “You will be. Just keep going. Áfram.”

From that day onwards, my relationship with Iceland shifted. I hurled myself into learning Icelandic and reading Icelandic novels, and the more I comprehended, the more I understood that Geirlaugur’s poetic sensibility was not an individual quirk but, rather, indicative of a wider cultural appreciation. I read Independent People by the Nobel prize-winner Halldór Laxness, where the farmer Bjartur composes stanzas while he labours. I read the Sagas of the Icelanders, where poets are ranked equal to warriors in prestige. As I found friendship and belonging in Sauðárkrókur, I realised that Icelanders’ respect for authors had not abated. One friend told me proudly that Iceland is a nation of writers: one in 10 would publish a book in their lifetime. Nowhere else in the world were as many titles published per capita.

I would not have become a writer were it not for Iceland. The enthusiasm for literature I saw around me that year – and the many times I have returned to the country since – renewed my confidence in the worthiness of writing as a vocation. Iceland herself, her sentient winds and blushing mountains, remain my muse. And if I feel the old self-doubt, the worry that I should be doing other things, I remember Geirlaugur’s gruff voice. “Áfram.” Onwards.

2 hours ago

2

2 hours ago

2