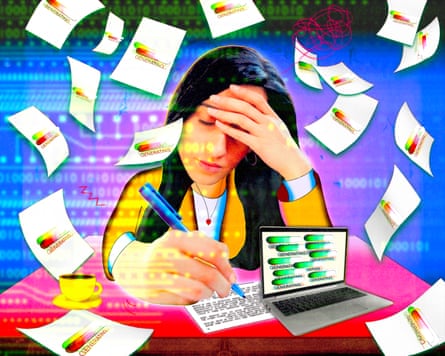

California-based Jacqueline Bowman had been dead set on becoming a writer since she was a child. At 14 she got her first internship at her local newspaper, and later she studied journalism at university. Though she hadn’t been able to make a full-time living from her favourite pastime – fiction writing – post-university, she consistently got writing work (mostly content marketing, some journalism) and went freelance full-time when she was 26. Sure, content marketing wasn’t exactly the dream, but she was writing every day, and it was paying the bills – she was happy enough.

“But something really switched in 2024,” Bowman, now 30, says. Layoffs and publication closures meant that much of her work “kind of dried up. I started to get clients coming to me and talking about AI,” she says – some even brazen enough to tell her how “great” it was “that we don’t need writers any more”. She was offered work as an editor – checking and altering work produced by artificial intelligence. The idea was that polishing up already-written content would take less time than writing it from scratch, so Bowman’s fee was reduced to about half of what it had been when she was writing for the same content marketing agency – but, in reality, it ended up taking double the time.

“I now had to meticulously fact-check every single thing in the articles. And at least 60% of it would be completely made up,” she says. “I would just end up rewriting most of the article. So something that would take me two hours when I was writing it by myself now took me four hours, making half the money.”

To add insult to injury, Bowman’s few remaining clients have sometimes accused her of using AI to create her work. “I never use AI to write anything,” she says, but she has noticed that AI-produced copy can sometimes seem eerily similar to her own writing – which she suspects is due to large language models being trained on some of her previous work. She can’t afford to take any of the Silicon Valley giants to court – though she is grateful for the authors, like George Saunders and Ta-Nehisi Coates, who have done so.

By January 2025, Bowman was no longer able to afford her own health insurance, which hammered home what she had already begun to suspect: “Writing is not going to work out for me any more.” She decided to bring her wedding forward (she and her partner are still going ahead with their planned celebration in March, but last year obtained a marriage certificate from their local courthouse) so she would be eligible to join her husband’s health insurance plan. But she knew a more drastic change would be needed before long.

She remembered a psychology elective she had enjoyed in college, and wondered if she might be able to make a more secure living by becoming a therapist. “It’s not AI-proof” – Bowman admits that some people will be happy to use AI-powered therapy services, which already exist. “But there’s another subsection of people who are going to say: ‘Hey, AI took my job, AI ruined my life. I’m not going to go to an AI therapist,’” she says. “So in that way, I do think that there’s still going to be an audience who wants a human therapist.”

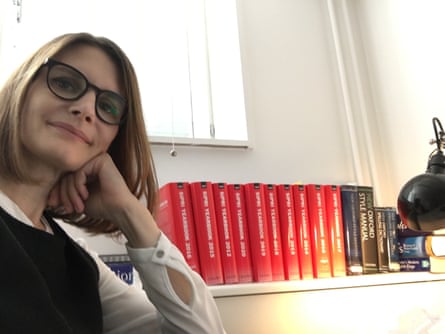

Bowman decided to take action and retrain, “while I still do have a little bit of work”, and is now back at university studying to become a marriage and family therapist. She counts herself “incredibly lucky” because she is able to rely on her husband, and on any writing work she can still get, to make ends meet – but has still had to take out loans. She’s enjoying the course, and is “glad she has the opportunity to do it”, but it is not something she would have considered if her writing work hadn’t become untenable.

Janet Feenstra, an academic editor turned baker based in Malmö, Sweden, also has mixed feelings about her career change, a choice she similarly made because of fears that AI would make her old job void. “It’s complicated because, in a way, I maybe should be grateful to AI for prompting this change,” she says. Feenstra now works at “a really cute bakery”, where she and her colleagues “roll out the dough by hand and it feels amazing”.

“We listen to music and we dance and sing whenever we want,” she adds. “I have a lot more fun now, but I don’t want to be grateful to AI for this – I’m still a little bit bitter.” It felt like a forced career change, rather than one she was choosing on her own terms, she explains – not to mention the fact that she now gets paid less, travels farther to work and does a much more tiring job.

Since 2013, the 52-year-old, who is originally from the US, had been working as a freelance editor alongside a part-time job at Malmö University doing what is called “language editing”: tidying up texts written by researchers whose first language isn’t English.

“The standard of English here in Sweden is very, very high, so this was very specialised academic editing,” she says. “The international journals are very picky, so it required a certain expertise that we could offer.” However, in recent years, she began to hear people within the university talking about wanting to use AI. “It was scary. I felt like the writing was on the wall a bit,” Feenstra says. She began to realise that if a manuscript “is already quite good”, then an AI system prompted to meet academic journal requirements might be able to do the work she had been doing.

“I didn’t want to wait until it was too late,” she says. “I felt scared … I’m divorced, I have two children to look after and I need financial security.” So she decided to retrain in something she “was fairly sure that AI would not replace anytime soon”, and enrolled in culinary school.

It wasn’t an easy transition. “I had to move out because I wasn’t able to afford my rent any more,” she says, which meant that her sons, who had previously lived between their parents’ two homes, had to live full-time with their father. While Feenstra embarked on her year-long training, she moved in with her partner, whose flat was too small to house her sons as well. Now, having worked in the bakery for five months, she has recently signed a contract on a new flat, which will have room for her sons. “I’ve had to work really hard: I’ve had to retrain, I’ve had to accept lower pay and conditions that are physically challenging,” Feenstra says. But securing the flat “is really exciting because it’s a goal realised”.

Feenstra says it has been “an interesting journey” to go from a job typically associated with middle-class people to one seen as working-class. “White-collar work isn’t all it’s cracked up to be, I’ve realised,” she says. “But it requires an adjustment. We’re so defined by our jobs and our class.”

Perhaps those definitions of what counts as a “good” or “middle class” job will begin to change: a 2023 report on the impact of AI on jobs and training in the UK by the Department for Education concluded that: “Professional occupations are more exposed to AI, particularly those associated with more clerical work and across finance, law and business management roles.” And, rightly or wrongly, Feenstra is not alone in deciding that learning a trade is a relatively safe bet.

Angela Joyce, the CEO of Capital City College, a further education provider in London, says: “We’re seeing a steady growth in students of all ages coming to us to do trades-based qualifications,” in subjects such as engineering, culinary arts and childcare. There is “definitely a shift” away from traditional academic routes, she says, which she attributes to the high numbers of unemployed young people – and “a good proportion of those are graduates”, she notes. That shift towards seeking vocational training is “in part linked to AI”, Joyce thinks, because people are looking for “jobs that AI can’t replace”.

That was certainly the case for Richard, a Northampton-based chartered occupational health and safety professional. After working his way up the career ladder for 15 years, the 39-year-old decided to jump ship and retrain as an electrical engineer.

“Health and safety isn’t going to disappear any time soon because organisations can’t name AI as a responsible person or a duty holder for businesses legally,” he says. But a few years ago, he started to hear “mumblings of AI” within the industry, and saw organisations start to experiment with automating certain systems and procedures. He watched as AI began to be used for writing policies and safe systems of work, and realised that if a large portion of practitioners’ workload could be done by AI, then there might only be a need for “highly specialised managers. The rest of it’s probably going to go.”

Though he decided to “pre-empt that” and pursue a different path, his main worry about AI taking over health and safety roles wasn’t actually that people like him would lose jobs – he finds aspects of AI “exciting” and accepts that it will inevitably shake up the way we work. His primary concern was that the implementation of AI might be “more of a cost-cutting exercise than it is about safety”. Richard cares deeply about the health and safety industry, which he entered after his friend was killed in a gas explosion at work.

He has taken “a huge cut” financially since he has been working as an electrical engineer over the past year, but his new job does at least still have keeping people safe at its core. And there is the potential to make the kind of money he earned in his old job once he has more experience under his belt, he says, but “I’m a good five, 10 years off”. And that’s if automation hasn’t come for electrical work by then – Richard mentions BMW’s testing of a humanoid robot as an example of how AI could affect trade jobs. Currently, though, the trades, in the UK at least, are “the most resilient to the levels of automation that AI is bringing in”, Richard believes. “Companies are capitalising on AI to remove one of their biggest costs, which is human overheads,” he says. “You need to pick something which has resilience. So, statistically, that is not your roles that are bureaucratic by nature, heavy in data and are just a bunch of processes which you repeat end on end. It needs to be something with high dexterity and some high problem-solving skills.”

Carl Benedikt Frey, an associate professor of AI and work at the Oxford Internet Institute, agrees that manual work “is going to be harder to automate”, but predicts that AI will have an impact “across a very wide range of industries” – trades included. “If the dishwasher breaks down in my home, I can take a picture and I can quiz the large language model of my choice, and I’m more likely to be able to fix it myself these days without calling an engineer,” he says. That’s not to say tradespeople are “doomed” – he cautions against making too many decisions based on “some hypothetical future scenario … We have to go by what’s actually happening in the labour market.” Which, now, is not a lot. “We’re beginning to see some studies suggesting more of an impact on entry-level work,” Frey says, but a reduction in entry-level job opportunities could also be attributed to higher interest rates, or post-pandemic recovery, he says.

“As AI gets better, and its capabilities improve, I think it’s likely that we will see it on a bigger slice of the labour market. But we’re not seeing it yet.” In fact, Frey has now reassessed his earlier claim that 47% of roles were at risk of being replaced by computerisation, made in The Future of Employment, the 2013 paper he co-authored with Prof Michael Osborne. “In that study, a lot of the jobs that we deem are highly exposed to automation are jobs in transportation and logistics because of autonomous vehicles,” he says. “It’s fair to say that it’s taken much longer for that technology to materialise.” As self-driving cars do begin to hit our streets, “we will see a lot of jobs being replaced in trucking and even in taxi services”, Frey believes. But his message seems to be don’t panic – at least not yet. “It might be a good idea if you are, say, in the early days of your professional career, to take the time that you still have to invest in training and figuring out other more viable career paths,” particularly if you work as a translator – one profession where “we’re already seeing that AI is having an impact, although we’re not seeing mass displacement by any means”. But if you are reaching the end of your working life, “you can probably ride the wave for a few more years”, he says.

The most significant AI-caused declines in employment and wages will be in jobs like software engineering and management consultancy, according to a King’s College London study published in October 2025. “That doesn’t necessarily mean that there aren’t going to be new jobs that will be created,” Dr Bouke Klein Teeselink, who authored that study, notes. Historically, whenever there have been technological advances people have worried about mass unemployment, but it hasn’t happened, he says. “So there’s a part of me that is a little bit sceptical that all the jobs will disappear, but at the same time there is a reason to think that this technology might be different, in the sense that humans always maintained some type of absolute advantage over technology in certain domains. And that may no longer be true.”

For now, while we can’t yet know the full impact AI will have on workers, “becoming really good at working with AI is probably going to be a skill that will pay off”, Klein advises. Which is what the Birmingham-based entrepreneurs Fayyaz Garda and Arun Singh Aujla, both 25, are attempting to do. Garda, who works in procurement, and Singh Aujla, who runs a social media marketing business, are in the process of setting up an AI consulting business, educating themselves about AI via YouTube. “It’s a growing market, and there’s definitely a space for it. So I’m hoping to try and get in there early,” Garda says. The plan is to employ a number of engineers to create AI systems that will answer phone calls, respond to mail and fulfil other tasks businesses need doing, he explains.

“The AI consulting business is one way I’m upskilling to move with the times,” Singh Aujla adds. “AI won’t replace me, but it may take a large market share out of my business. So it’s always good to make an extra stream of revenue.” There are certain roles Singh Aujla would never replace with AI, though: “I would not replace my management team. You need that human interaction with your team,” he says. “But roles the team don’t want to do, like email outreach and cold calling, we can get AI agents to do that.”

For some, it may well prove true that AI improves their work life by removing tasks they find tedious or difficult, giving them more time to focus on the more fulfilling aspects of their job. For others, though, it is the reason they have given up on their dream career. Paola Adeitan, 31, had her heart set on being a solicitor, and obtained an undergraduate degree and a master’s in law. She had planned to do the legal practice course, the final stage of training needed to qualify as a solicitor, “but I decided not to pursue that path because I felt like, with the change in technology, the AI, that might not be a viable path for me to carry on with,” she says. Friends of hers had struggled to get entry-level law roles, which she believed to be partly due to the increased use of AI at law firms.

Adeitan still volunteers as a legal adviser, but her day job is in the health sector – although even that role could be affected by AI, she thinks, so she is remaining open to the idea that she might end up retraining again. “I do feel a sense of disappointment,” she says, “but the nature of work is changing. It’s very difficult now to decide what you want to do; you have to think carefully. It’s not about what you want any more; it’s about what is going to be there, what’s going to work.”

If you’re lucky, what ends up working best could be something you really enjoy – as is the case for Faz, 23, who took a break from his geography degree at the University of Manchester in 2023 because of a family matter. Afterwards, it didn’t make sense to him to return to his degree. “I had to think about what was future-proof, I had to think about what was AI-proof. And it seemed like a lot of entry-level roles in the corporate sector were being taken over by AI. And because AI is so unpredictable, you never know if those more specialised roles will also become obsolete,” he says. So he has instead been training for a Level 2 qualification in electrical installation since September 2025. “I thoroughly enjoy it,” he says. Though he might go back to university at some point – his “ideal setup” would be a combination of working part-time for a council or a charity, while doing electrical work on the side – “right now, a tradie job is 100%, God willing, the correct choice. I’m fairly certain it will be future-proofed against AI.”

Bethan, 24, from Bristol, also enjoys her AI-proof job, working in a local cafe. But it comes at a cost: she has hypermobility spectrum disorder, which gives her severe joint pain and makes it hard for her to move around. “I can’t work long hours now because I’ve pushed my body past the point,” she says.

Bethan’s old job, at a university IT helpdesk, “was the first job that I didn’t come home in pain from”, she says. But only a couple of months after she was hired, she and her colleagues were told the helpdesk was being closed down and replaced with an AI kiosk. “It was awful,” she says. The helpdesk staff tried to defend their roles, arguing that for students who didn’t speak English as a first language, or older students who weren’t computer-literate, having humans behind the desk may still be necessary. “It felt like we were getting completely ignored. They went ahead with it because they said they had to get a certain number of cuts to the budget.”

Hospitality was the only other sector in which she had experience, so she ended up at her cafe job. “Feeling like I had to go back to hospitality, which was so bad for my body, was a horrible feeling,” she says. She is now on the lookout for an office job, but has struggled to find anything entry-level. “Those are the jobs that are vanishing because they’re the easiest to replace,” she says – but it also means it is impossible to get the experience needed for higher-up roles. Bethan worries that even if she does get an office job, she could lose it to AI again. “Is it worth all the effort of applying, getting my CV up to date, and potentially doing a couple of rounds of interviews just to find out at the end we’re going to be replaced again?”

With more physically demanding jobs making up the bulk of what is now considered “AI-proof”, those who have made the switch from white-collar roles are having to adapt to the toll it takes on their bodies. The electricians Richard works with are typically in their late teens and early 20s. “Their recovery rates are a hell of a lot quicker than mine. So if I pick up an injury, for example, it takes me far longer to recuperate. Also, they can work far longer hours than I can,” he says.

And though Feenstra enjoys the physicality of working in a bakery, she has been thinking about how sustainable this kind of job will be as she gets older. “That’s why I’ve been taking note of how the owners run the business,” she says, in case there is a possibility of running her own bakery one day. She is proud of how she is continuing to adapt to the changing world around her: “I want my sons to feel a little bit inspired by that,” she says. Yet she doesn’t feel she can offer them career advice. “How am I supposed to advise them when I don’t even really know if what I’m doing is the right path?” she says. “It’s really unsettling when you can’t advise them. If they have a passion for something and they want to do something, immediately you think, OK, is this even going to exist in the next 10, 20 years? That just kind of sucks.”

Ballerinas will still exist, says Klein. “No one is going to go to the ballet to see a robot do really good ballet,” the academic says. “Same for theatre, same for football, same for many other things where it matters that there’s a human.” He doesn’t think people will be wanting to confess to robo-priests any time soon either, or leave children in the care of AI. “There are just categories where we prefer to interact with humans, right?” For that reason, social skills will remain important, Klein and Frey agree. And though it might seem as if AI could make expert knowledge useless, Klein disagrees. “I have students who use AI naively, and therefore they have no idea whether the reports they produce are good or bad,” he says. “You need to have that expertise to be able to guide the AI to get it to do what you need it to do. So in that sense, I think the value of expertise might actually go up.”

How such expertise will be developed, if entry-level jobs are being ditched in favour of AI systems, is a question that remains as yet unanswered, as is who will actually be able to buy a ticket to the ballet should large swathes of the population be put out of work. But Frey doesn’t think it is worth spending too much time worrying about that potential future – yet. “It could well arrive, but it matters a great deal if that happens in five years or 20.” While he acknowledges “there are reasons to be concerned”, Frey doesn’t think it’s time to “paint a scenario where everybody’s going to be out of work five years from now, and we need to rethink everything”.

2 hours ago

1

2 hours ago

1