Aged seven or eight, planting onions on his father’s land above Kabak Bay, Fatih Canözü saw his first foreigner. Before the road came in 1980, his village on the jagged coast of south-west Turkey’s Lycia region was extremely remote, isolated by steep valleys and mountains plunging into the sea. It took his family two days to get to the city of Fethiye on winding donkey tracks, to sell their apricots, vegetables and honey at the market. Despite his shock at seeing the outside world intrude for the first time, Canözü remembers thinking even then that tourism was the future.

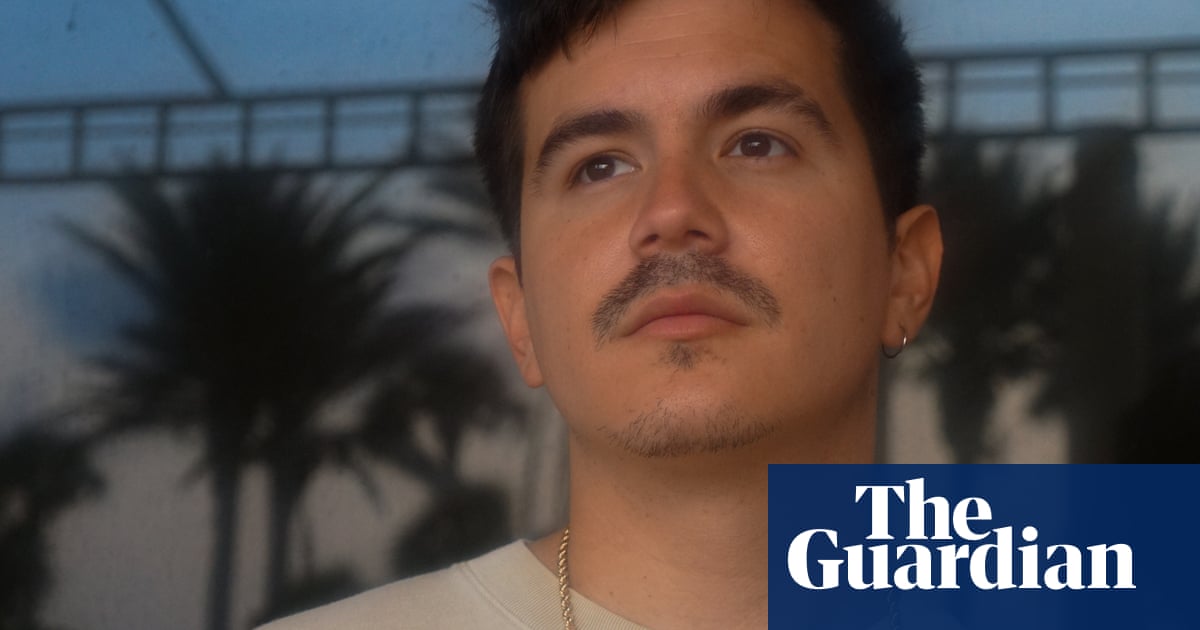

Four decades on and having trained as a chef, Canözü has not only built a restaurant and 14 tourist cabins in Kabak, he has married a foreigner too: a former Middle East correspondent from England, who came here to research a novel and ended up falling in love. Now they are raising their family on this wild fringe of Anatolia’s Turquoise Coast, a region that Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, founding father of the Republic of Turkey, is said to have called the most beautiful in the country.

The Olive Garden takes its name from the 200 to 300 olive trees growing on the terraced hillside above the sea. Canözü’s father dug them up in the mountains and lugged them here on his back, a testament to the years of hard work it took to make this place. Canözü designed the cabins himself, building them in wood and stone to minimise the environmental footprint. Then he installed an infinity pool where his family once threshed grain. When the restaurant opened in 2005, he waited a nerve-racking 45 days for his first customer. Slowly, people came.

My wife and I stay here for four nights, sleeping first in a standard cabin and then in one of two luxury cabins overlooking the sea. The room is airy, glass and pine, but we spend most of our time sitting on the deck outside, continually astonished at the view. On the far side of the forested valley rise immense limestone walls that mark the southern reaches of the Taurus mountain range – the summit nearby is slightly lower than Ben Nevis. On the beach below, a sliver of sand meets startlingly blue water. Kabak beach has long been known for its alternative vibes, a place where groups of hippies sunbathe alongside Muslim families, women in burkinis and dogs dozing on the sand.

This sense of coexistence – something that many see as the heart of modern Turkishness – extends to the marine life: at sunset, half the beach is cleared for nesting loggerhead turtles.

By road, the village of Kabak is literally the end of the line, which, along with the rugged terrain, has helped shield it from the overdevelopment suffered by resorts elsewhere.

On foot, it is a resting place on a longer, slower journey. One of the things that brings travellers here is the 470-mile Lycian Way, established in 1999 by a British-Turkish woman called Kate Clow, who still lives locally. We hike sections of this world-renowned walking trail, first along a rocky path through pine forest and strawberry trees to visit a nearby waterfall. Some beach party stragglers have landed after a long night, so we take our plunge to the thump of techno. A few minutes’ scramble and the trail brings us back to wild silence.

The following day I walk south for two hours while others go ahead by boat; we meet on Cennet Koyu, which translates as Paradise Bay. No road has made its way to this beach, and it fully deserves its name. Swimming here, in water as clear as glass with steep green mountains rising behind, is as close to paradise as can be imagined. Up in the forest is one of the “camps” that were founded before gentrified tourism arrived – vaguely piratical travellers’ outposts that keep things reassuringly scruffy. Dogs, chickens and donkeys wander among the trees.

The boat, steered by a local man with an anchor tattooed behind his ear, takes us around the next headland to the site of a ruined village. Its archway and collapsed stone walls, half swallowed by greenery, are a testament to the darker history of this stretch of coastline. Kalabantia was once inhabited by Greeks, forced to abandon their beautiful home during the brutal “population exchange” that followed the Turkish war of independence in the 1920s. No one came to take their place – it was too remote even for local Turks – so now its stones are sinking back into the land from which they came.

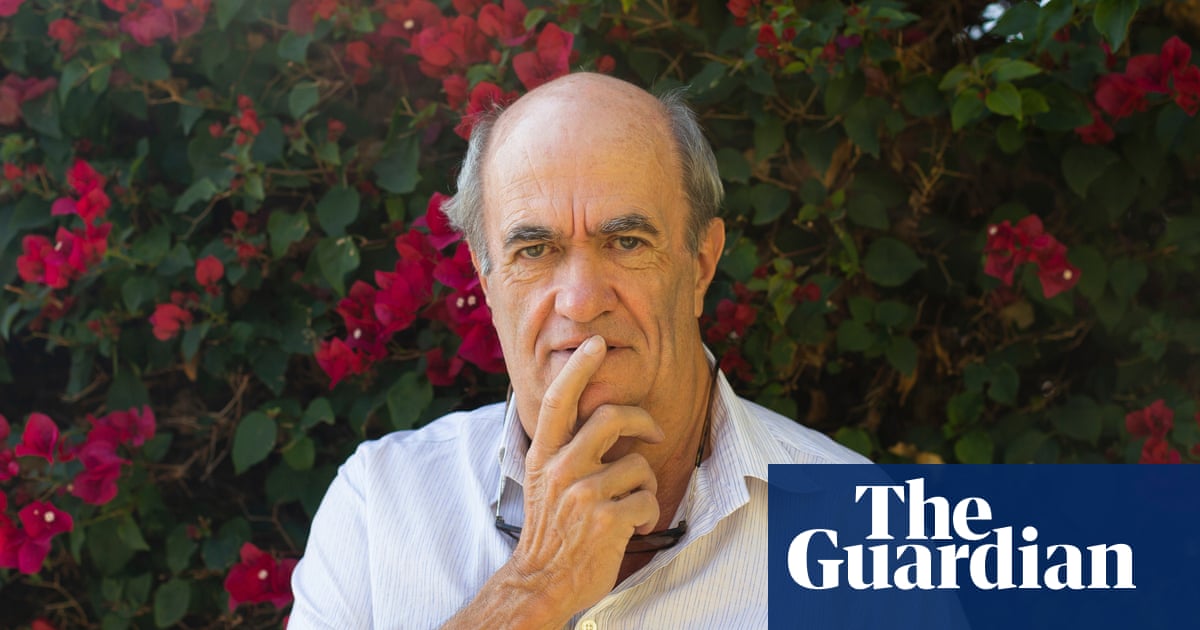

A 45-minute drive away is the much larger settlement of Kayaköy, formerly Levissi, from which over 6,000 Greeks were deported in 1923 to a “homeland” they had never seen. This melancholy ghost town of 500 roofless houses is almost entirely abandoned, but for roaming goats and tourists. There is something particularly tragic in its Orthodox chapels and churches, with their painted stars still pricking the ceilings. Strangely, I realise I’ve been here before: under the fictional name Eskibahçe, this was the setting of Louis de Bernières’ novel Birds Without Wings, which describes how nationalism tore apart multicultural communities that had lived side by side under Ottoman rule for centuries.

after newsletter promotion

The Greek influence is also apparent in Lycia’s most famous ruins: the rock-carved tombs that we saw on our way here from Fethiye. They were made by the ancient Lycians, who blended Hellenic architecture with the Persian technique of hewing structures from the living rock. Smaller tombs, which resemble lidded caskets made of stone, are scattered throughout the mountains and along the Lycian Way, monuments to another of Anatolia’s vanished cultures.

Life has never been settled here. Kabak might still be remote but the road has inevitably brought change, and since the Olive Garden opened, trees have been bulldozed and concrete poured, although the pace of construction has apparently slowed in recent years.

With increasing visitor numbers, the water supply is a big concern, followed closely, in this time of ever-rising temperatures, by the risk of forest fires. But other things stay much the same. Where the road terminates the mountains are still vast and wild, the forests are still full of boar, and the turtles still return to the beaches every year. As in other places where beauty masks a harder existence, there’s a balance to be struck: without tourism – including the hikers slogging along the Lycian Way – many of Kabak’s young people would be forced to move elsewhere instead of working locally, as the Olive Garden’s staff do. At least for now, Kabak feels on the right side of that balance.

On our last night we eat imam bayildi, which translates as “the imam fainted” – presumably because the dish is so good – roasted aubergine stuffed with onions, tomatoes and garlic, drenched in olive oil and smothered with melted cheese. The food has been consistently fresh, local and delicious. The moon shines on the walls of the valley, which glow as bright as bone. We have learned a new word, yakamoz, my favourite in Turkish or any other language: it describes the sparkling of moonlight on dark water. There is poetry in this land. Any culture that has a word for this must be doing something right.

Standard cabins at Olive Garden Kabak (olivegardenkabak.com) from £70, luxury cabins £120 (both sleep two), breakfast included

5 hours ago

4

5 hours ago

4