Poem in which I’m a transnational drug smuggler

The guy in front of me is told to remove his leg. He unscrews

it and places it in the tub with his luggage. We watch

his leg disappear through the rubber curtain

as he hops through the airport scanner. His stump

is swabbed alongside another guy’s empty boot,

a tube of toothpaste and a wallet. I’m asked to wheel

past the metal detector and to park myself

where the other travellers await their bags.

A female guard cups my arms, my waist, my breasts.

She asks me to raise myself above the cushion, squeezing

her hand into the gap between my skin and chair.

Below, my five-hundred-pound pressure cushion

protects my skin, bags of coke stashed where the gel

should hold my form. Each bum cheek is perfectly imprinted

in bleached powder. Later, when the taxi driver asks

whether my wheelchair is to support

my benefits claim, I’ll smirk and nod.

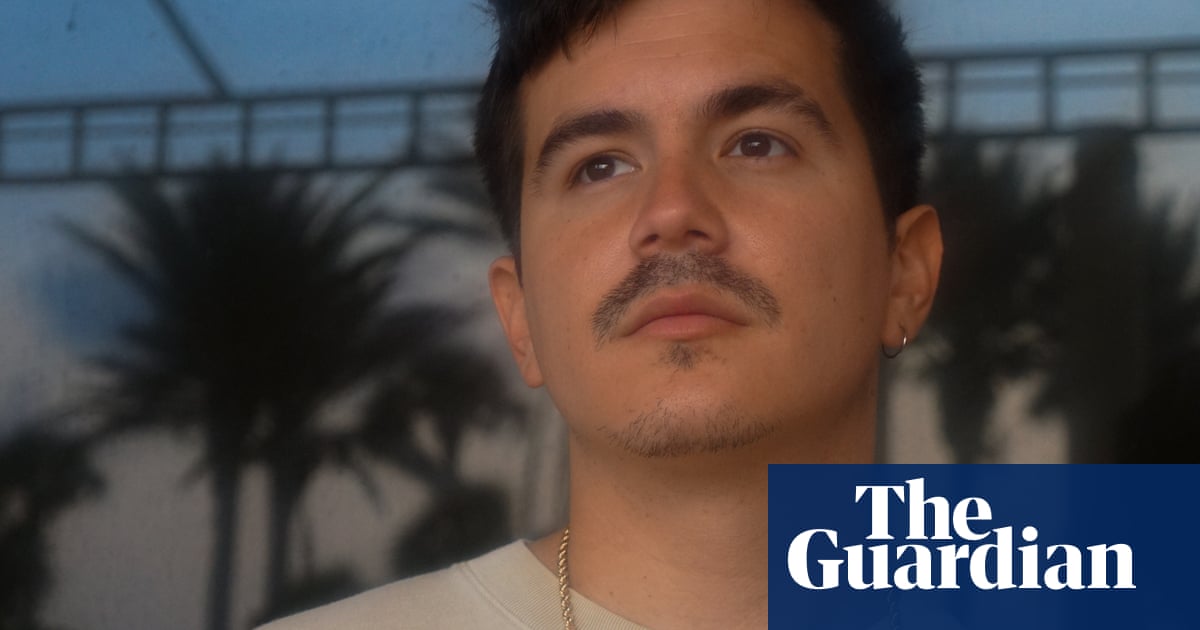

“Ableism. The act of wrapping the world in cling film.” Bethany Handley extends the metaphor further in the title poem of her recent pamphlet, Cling Film. It’s also “the film you’ve wrapped me in / as I move with palms open to the clouds / whilst yours are bound to the ground”. Disability can refresh the senses: it can have the force of poetry.

Politics dictate the poetics in other poems, such as The Heath, where multi-spacing, erasure, typographical emblems, etc, visualise the disorientations created even in settings where the medical establishment seriously attempts to investigate an unfamiliar disability. Other poems use smoother lineation and more traditional stanzas paradoxically to express the enhanced bodily awareness which is liberating, and reintegrates the poet with the natural world she loves. “Swifts’ legs are fingers, not fists. They don’t pound but stroke the earth,” she writes in a paean, A Swift’s Flight, inspired by the arrival of her first wheelchair, and the accompanying dreams of flying above Cardiff.

Other poems are direct, scathing accounts of ableist insults and ignorance: they are eye-openers for anyone who hasn’t encountered the daily round of prejudice that people with disabilities face. This week’s poem is one of those. It’s powered by sharp observation and impeccable self-restraint.

The title, Poem in which I’m a transnational drug smuggler, memorably announces a first-person narrative. It subverts expectation initially by looking outwards, watching what happens in airport security when “the guy in front of me is told to remove his leg”. The ensuing short description recreates not only what’s happening to the “guy” but also the way he becomes the central focus of the ableist gaze, stared at and humiliated “as he hops through the airport scanner”.

The narrator introduces her own encounter with security in a casual, end-of-stanza use of the passive voice: “I’m asked to wheel // past the metal detector and to park myself / where the other travellers await their bags.” Like the man with the prosthetic leg, she’s reduced to an object among other objects. Directed to her “place”, she might as well be an item of baggage.

The intrusiveness of the body search performed by “the female guard” is made only too tinglingly clear in stanza four, where the guard’s hand “squeeze[es] /… into the gap between my skin and chair”. The gap is narrow, because the user has had to raise her own body weight from the chair to allow the intrusive inspection. Now the final phase of the search takes place. Instead of expressing a legitimate indignation, the speaker calmly goes along with the assumption that there may indeed be “bags of coke stashed where the gel / should hold my form”. The voice remains steady as it forensically notes that “each bum cheek is perfectly imprinted / in bleached powder”.

Handley has found her weapon. She will be able to resist the further brutal thrust of prejudice which she has learned to expect: “… when the taxi driver asks // whether my wheelchair is to support / my benefits claim, I’ll smirk and nod.” Allowing herself to enact the “transnational drug smuggler” fantasy, she’s armed with perfect sardonic control, matched by the parallel technical control of the poem’s judiciously sharp line breaks and plain diction.

There are more overtly angry poems in the collection, and they are powerful, too. There’s an infectious relish when a friend is patronisingly offered help with the wheelchair that’s got stuck in deep sand, and Handley throws him her “piss off mate, we’re doing fine thanks look”. (Hiya Butt Bay). Mockery, like revenge, is “a dish best served cold” but it’s also tasty warmed up, as in another exposure of officially sanctioned idiocy, the “work focused interview” demanded by the Universal Credit system. “Can’t you work lying down / with headphones on?” an official asks a suffering applicant. “Your goal for finding work this month / is to learn to sit up.” (Attended Work Focused Interview).

Handley is an award-winning disability activist as well as poet, and she knows how to write a poem that expresses strong principles without removing the poetry. She makes us acutely aware of the truth that people are disabled by the system that labels them and pretends, with total lack of imagination, effort and adequate funding, to meet their needs. Cling Film is a collection that lifts many veils and lets in much-needed light and air.

3 hours ago

2

3 hours ago

2