‘There is no creature born, even among the greater apes, which more resembles a human baby in its ways and its cries than a baby grey seal,” wrote the ecologist Frank Fraser Darling in 1939. Seals’ large eyes, the five digits of their flippers, their lanugo – the soft down with which they (and sometimes we) are born – all erode the mental barriers we erect between ourselves and our marine cousins. According to Faroese legend, there are even seals, known as selkies, that can shed their skins, assume human form and live undetected among us.

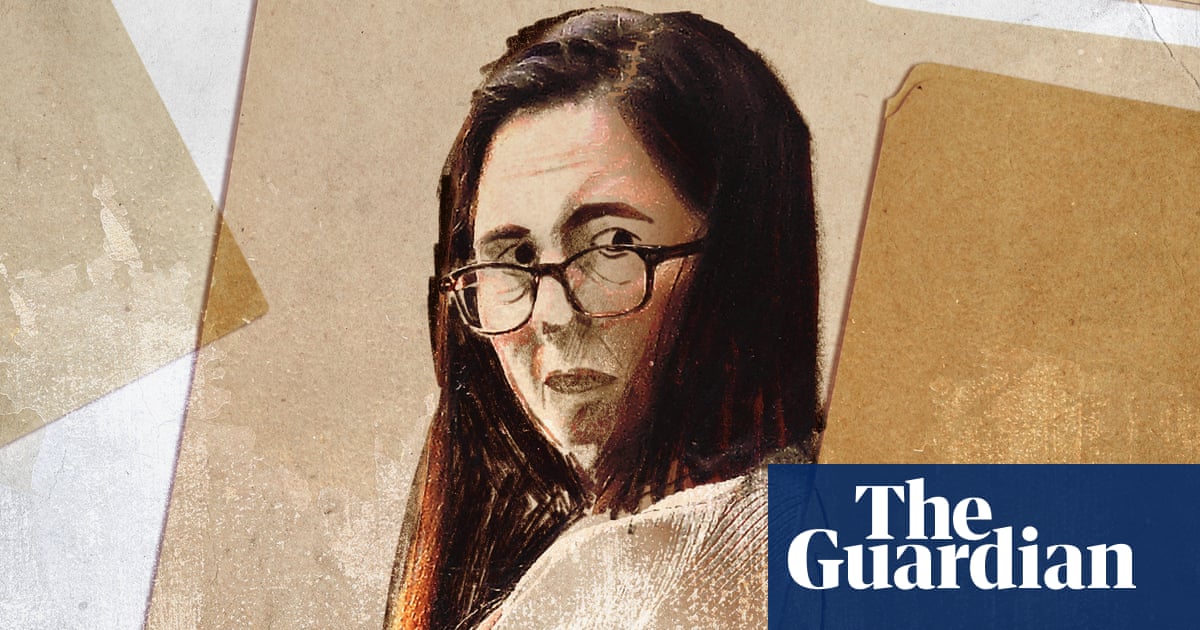

The selkie myth is just one that appears in the Maine-based science writer Alix Morris’s compelling book, which explores seals’ fraught relationship with culture, the economy and our imaginations. She charts the varied and conflicting ways in which we conceive of these creatures: as reviled competitors for fish, magnets for great white sharks, or defenceless human children who “weep” when distressed.

Seals do not actually weep under the influence of emotion (they do so to moisten their eyes), though they have had reason to feel sadness and terror. Viewed as a threat to fisheries, they were hunted in the US under a bounty system in the 19th and 20th centuries; by the 1970s grey seals were in effect eliminated from the country’s waters. In recent decades the numbers of grey and harbour seals have recovered, largely thanks to the Marine Mammal Protection Act of 1972. In an era of widespread species loss, the reappearance of seals has been a conservation success (though hunting had a major impact on their genetic diversity).

Not everyone is pleased with the seals’ return. Intelligent, nimble and creative, they can catch their own fish, but will never turn down a free or discounted meal found in a net, on a fishing line or fish ladder (an “all-you-can-eat seafood buffet”). Morris’s descriptions of pilfering seals often made me smile, but the joke is lost on the fishing community, who view them as a threat to already depleted stocks. Even more charged are the concerns of Maine bathers, some of whom say seals attract sharks close to the shore. In their reading, the presence of seals poses a threat to human life.

Set against this mistrust, and even hatred, are stories of care and concern by conservationists who spend their days and nights nursing seals harmed by fishing nets, predators or beachgoers suffering from a “seal saviour complex”. In Morris’s telling, the last type is a particularly male pathology: one kayaker, believing that a baby seal was threatened by seagulls, took it home, placed it in a waterless bathtub and proceeded to offer it cat food, striped bass and milk (the seal refused to eat, and later died, despite the emergency assistance of a marine mammal NGO). With seals, there is a blurred line between adoption and abduction.

Like Fraser Darling, Morris feels drawn to the seals, welling up with emotion when a rescued pup dies, and even offering her lips to a seal in an aquarium. But she is also aware that she has little to lose from a stolen fish or a roving great white. While she notes that seals have indeed reduced fish numbers in some places, she sees the effect as minimal when set against the harms of industrial fishing, damming and climate change. Seals, she suggests, are marine scapegoats, a distraction from wider conflicts in the US that have very little do with them.

I live in Scotland, close enough to the water to see seals, but not to know them, their smell, their thick whiskers, blubber, or lanugo. While Morris offers tantalising glimpses of these creatures, I wished there was more in this book about their lives, their anatomy, their relationships and sociability. As she points out, seals spend so much of their time underwater that we still know very little about them. They remain as elusive as the selkie.

3 hours ago

2

3 hours ago

2