Some cultures used stone, others used parchment. Some even, for a time, used floppy disks. Now scientists have come up with a new way to keep archived data safe that, they say, could endure for millennia: laser-writing in glass.

From personal photos that are kept for a lifetime to business documents, medical information, data for scientific research, national records and heritage data, there is no shortage of information that needs to be preserved for very long periods of time.

But there is a problem: current long-term storage of digital media – including in datacentres that underpin the cloud – relies on magnetic tape and hard disks, both of which have limited lifespans. That means repeated cycles of copying on to new tapes and disks are required.

Now experts at Microsoft in Cambridge say they have refined a method for long-term data storage based on glass.

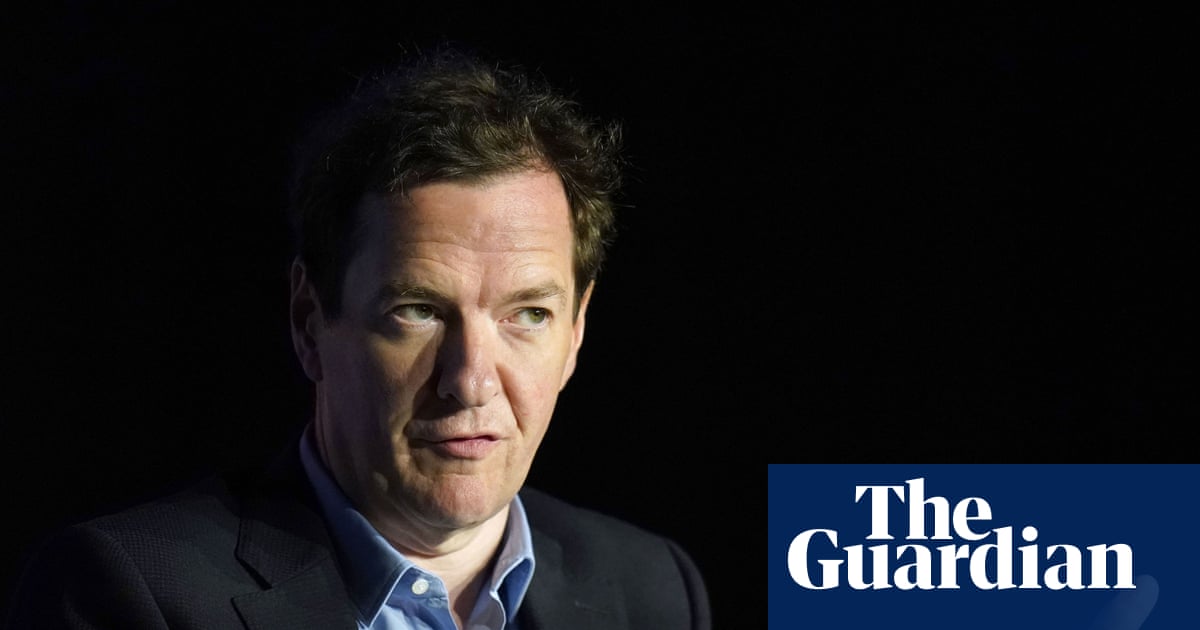

“It has incredible durability and incredible longevity. So once the data is safely inside the glass, it’s good for a really long time,” said Richard Black, the research director of Project Silica.

Writing in the journal Nature, Black and colleagues report how the system works by turning data – in the form of bits – into groups of symbols, which are then encoded as tiny deformations, or voxels, within a piece of glass using a femtosecond laser. Several hundred layers of these voxels, Black notes, can be made within 2mm of glass.

The system uses a single laser pulse to make each voxel, making it highly efficient. By splitting the laser into four independent beams writing at the same time, the team say the technology can record 65.9m bits per second.

The researchers found they could store 4.84TB of data in a 12 sq cm piece of fused silica glass, 2mm deep – about the same amount of information that is held in 2m printed books, an accompanying article by researchers in China notes.

The team have also developed a way to create voxels in borosilicate glass, the material used by the Pyrex brand.

“It’s much more commonly available, it’s much cheaper, it’s easier to make manufactured,” said Black.

Once written, the voxels can be read by sweeping the glass under an automated microscope with a camera to capture images of each layer. These images are then processed and decoded using a machine learning system.

“All steps, including writing, reading and decoding, are fully automated, supporting robust, low-effort operation,” the team write.

They add that the data storage system is very stable, with experiments suggesting the deformations created by the laser would last more than 10,000 years at room temperature.

However, Black said the technology was unlikely to end up in a home office, instead noting that the system was intended to be used by big cloud companies.

Melissa Terras, professor of digital cultural heritage at the University of Edinburgh, who was not involved in the work, welcomed the study.

“Any type of storage that allows for long-term digital information management is exciting, particularly if the media is inert and has the potential to last without special maintenance,” she said.

But, she added, potential difficulties remain – including whether the instructions and technology for reading the glass would remain available for future generations.

And there is another issue: significant investment would be needed to deploy Silica at scale. “We are not in an economic moment where industry or politics is choosing to build infrastructure that will support the information needs of future generations,” said Terras.

“I’d recommend that if that was a concern, we should pour our scant resources into fixing the aftermath of the cyber-attacks on the British Library, to ensure the information we already have in known formats is stewarded and available to users now and in the future.”

6 hours ago

7

6 hours ago

7