Clémence Polès Farhang started Passerby magazine around the time she immigrated to New York City. She says she wanted to explore womanhood as she navigated her own, and used publishing as a way to “deconstruct the internalized misogyny” from her own education. Polès Farhang’s mother, who left Iran during the revolution, believed women should have the right to choose what to do with their bodies, “yet would dismiss any woman who didn’t conform to conventional expectations,” says Polès Farhang, such as those didn’t dress “in a way she considered put together, or didn’t marry into heteronormative relationships within the right social class.”

“I remember being scolded in my early 20s for embarrassing her by leaving the house barefaced,” she says.

Photography gave Polès Farhang the autonomy to look at women differently than she had been taught to. “I turned my upbringing’s fixation with appearance into a sensitivity in my work. What happens when you meet it with curiosity rather than judgment?”

That question became Passerby – a decade-long photographic and oral archive of more than 300 women, photographed in their homes across New York, Paris, London and Los Angeles. To celebrate the 10-year milestone, the New York gallery Slip House is hosting Polès Farhang’s first solo exhibition, Can I come over and take your picture?, curated by Nastasia Alberti – more than 200 photographs taken for Passerby, paired with quotes from their corresponding interviews.

While preparing the exhibition, Polès Farhang realized that most of the portraits were of immigrants or children of immigrants. For most of them, that displacement directly shaped who they became: their work, their sense of home, their relationship to belonging.

“I thought of Carmen Winant’s The Last Safe Abortion, how she realized anti-choice activists used photography as a tool, and how she could use the same medium for abortion care,” says Polès Farhang. “What images are used in contemporary immigration discourse? The language is always about movement – people coming, crossing, arriving, being stopped. Immigration framed as a problem to be solved, a flow to be controlled, a crisis to be managed. How are we showing otherwise?”

These portraits show another facet of immigration: women building homes and making art. The captions are extracts from their Passerby interviews.

Huong Dodinh

Dodinh was born in Saigon, and fled her home in the Mekong Delta, Vietnam, with her family at eight in 1953 due to war. They settled in Paris, in front of the Luxembourg gardens. “In Vietnam, we had no winter, so it was always lush.I remember seeing these trees in Paris bare – fallen leaves, I thought they were all dead.” In France she was placed in boarding school – a severe environment, very hard for a little girl who didn’t understand French. “I remember the box spring beds, with a mattress on top. I couldn’t sleep because, in Vietnam, we slept on hard, hard, hard beds. So, I wasn’t used to sleeping on soft mattresses.” She attended École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts beginning in 1965, was there for May 68. She met her husband through a Vietnamese association that gave free lessons.. Now she lives a monastic life, rarely leaving the house except for necessities nearby.

Photographed in the 20th arrondissement, Paris, 2024.

Rose

Rose is from Guerrero, Mexico. She arrived in New York in 2000 at 22, leaving behind her children – the youngest was just a year old – to give them a better life. Upon arrival her taxi driver asked me where she was staying, and she told him “If this is New York, you can leave me here.” It was 26 February, and it was snowing. The driver said he couldn’t leave her on the street. He took her to his workplace at an Italian grocery store, introduced her to the manager as his sister, and got her a room for $25 a week. She started working the next day.

Rose had two children starting when she was 14, both the product of rape. “My kids are the motor that keeps me going every single day. I tell myself that all of this happened to me because I was too young to take care of myself and didn’t have anyone to protect me, but this will not be my children’s story.”

She loves shopping at Marshalls and particularly loves wearing dresses and extremely high heels that she “can barely walk in”.

Photographed in Harlem, New York City, 2022.

Shirin Neshat

“I grew up like many Iranian people in my generation, fantasizing about America through Hollywood,” says Neshat. “But when I arrived in Los Angeles, I felt a lot of depression. We were always in the car and on the highways and in these ugly apartments. I terribly missed my home.”

She found herself alone at UC Berkeley during the Iranian revolution around 1979. “I really lost contact with my family. Then Iran started a war with Iraq and there was major antagonism against Iranian students on the campus.”

After meeting her partner, Shoja, she gathered Iranian artists around her – cinematographers, singers, writers, film-makers – and they became an extended family. “Whatever Iranian that stayed in me is very deep. I never realized how much your childhood stamps you your for ever.”

Photographed in Brooklyn, New York City, 2022.

Ana Kraš

Kraš was born in Belgrade. The Bosnian war began when she was seven. “The borders were closed and embargos ushered in some of the worst inflation in the history of the world, followed by bombing. Looking back, I see that it wasn’t the most average childhood, but growing up in difficult circumstances is a kind of blessing. I don’t think having abundance is a good environment for development.”

At 15, she convinced her parents to let her go to Tokyo to work as a model. “It was way before mobile phones were prolific, so it’s crazy that they let me go. I had to take a minivan to Budapest to fly out of Hungary, as the airports in my country were shut down because of the war. In my head, this trip marks the end of my childhood. I made money for my family, which was very needed, as my sister had a baby just after the bombing, and we had so little at that time. I loved the feeling of being a grownup, a provider.”

She moved to the United States in her late 20s. “I had to do so much work that I didn’t like or care about, and I made so many compromises. .” Now she loves to spend six or seven hours a day alone at home, not interacting with anyone. “I think, looking from the outside, people might assume that I am much more social.”

Photographed in the 11th arrondissement, Paris, 2023.

Isabel Sandoval

Film-maker Sandoval was born and raised in Cebu, the second-largest city in the Philippines. She moved to New York a year after graduating college. “I didn’t realize I was trans until some time after moving to New York..”

She says still finds identity politics can be “a double-edged sword”. On one hand, she says, “it’s great to have your stories represented but it can also inadvertently marginalize you. The industry can keep you in that box. I’m making a conscious effort to transcend that label and approach new projects with the perspective of pure artistry, not just gender.”

Photographed in Crown Heights, New York City, 2020.

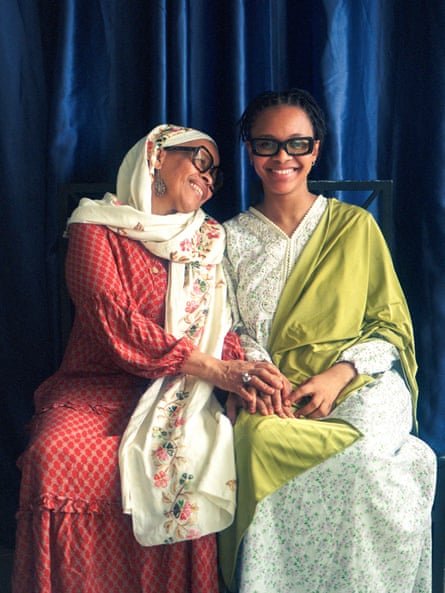

Naïlat Salama Djae and Salimata Ali Chahidi

Mother and daughter Chahidi and Djae immigrated from the Comoro Islands, where Chahidi grew up and where Djae was born, they have created a vibrant and comfortable life for themselves in Paris, where Salimata is a social worker helping refugees and Naïlat is a PR manager.

Chahidi helps asylum seekers prepare their files. “The most emotional part is preparing the asylum file because it’s their whole life. You learn what made them leave their country to come here.” She helps them translate their life into a narrative that answers three questions: “Why am I coming here? What do I want here and how? Why did I leave my country?”

They’re different in how they express emotion. “When I’m angry, I’ll say it straight away. When I’m very happy, I’ll say it straight away. I’m very into talking and she thinks that’s very gen Z. Mom will keep quiet and wait until the time is right to say something,” says Djae.

Photographed in L’Haÿ-les-Roses, outside Paris, 2025.

Tiana Rainford

Rainford grew up in East New York, raised by a Jamaican immigrant mother who is a trained chef. She still lives in the neighborhood – now working at a community farm, growing organic produce and helping feed and educate her neighbors.

“My mom was really conscious of what we ate. She really emphasized the importance of eating at home, making our own meals, and eating fresh foods. Her father was a farmer too. So food has been really important to us forever.”

When her mother had health scares, her medical advisers didn’t understand her diet. “My mom eats food that is culturally relevant to her and they made her afraid to eat the things she normally eats. Like, it may not be a norm for you to eat yam every morning or every day, but that has been a part of her diet and her culture for a long time. It didn’t feel right for someone to tell her she couldn’t eat that any more.”

Photographed in East New York, 2024.

Sunny Shokrae

Shokrae is a photographer who left Iran as a young child and was raised in southern California. Unfulfilled with post-college life, she moved to New York to pursue photography. In 2010, she went back to Tehran to do a story on the underground music scene. At a flea market, she watched a stranger check out a Black Sabbath record and walked up to him because they had something in common. “I think because I left Iran at such a young age, I’m always looking for things to connect me back to this place I know so much about and have so much admiration for but have spent such little amount of time in.”

Photographed in Bed-Stuy, New York City, 2023.

-

Can I come over and take your picture? is at Slip House New York

2 hours ago

3

2 hours ago

3