This inexpressibly painful and sad story – featuring angry, complex, brilliant late-career performances from Tom Courtenay and Anna Calder-Marshall – is about dementia, the endgame of care and the decisions that need to be made when the spouse-carer is as vulnerable as the patient (and whose right it is to take those decisions). It is about the nature of intimacy between the two; and about the moment this becomes a problem for the grownup children with a conflicting sense of their own responsibilities.

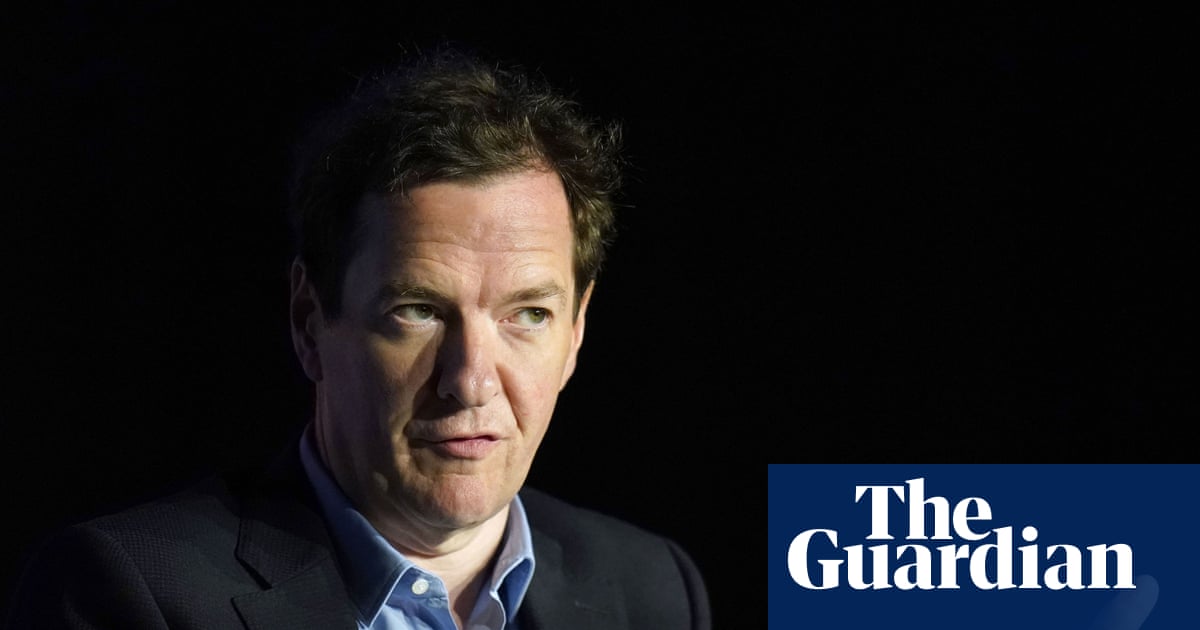

Queen at Sea is directed by indie US film-maker Lance Hammer, absent since his 2008 Sundance winner, Ballast. This is an almighty comeback, a lacerating movie bearing comparison with Michael Haneke’s Amour or Gaspar Noé’s Vortex. It concludes with a heartbreakingly ironic and enigmatic final sequence refusing the traditional final cadence; a diptych of love, contrasting the pleasures and expectations of intimacy across the generations.

The setting is a gloomy and wintry London, with porridge-grey cloud cover. Juliette Binoche plays Amanda, a recently divorced academic. She has taken a sabbatical with her teen daughter, Sara (Florence Hunt), to be closer to her elderly mother, Leslie (Calder-Marshall) – who has dementia – and her stepfather, Martin (Courtenay).

One dull weekday morning, she looks in on Martin and Leslie, catching them having sex, with a mask of incomprehension on her mother’s face. Furiously, she accuses him of raping Leslie. The shock and disgust clearly stem at one level from the fact that he is her stepfather, not her father; and also because they have already received the GP’s advice that Leslie can no longer give meaningful consent.

Yet Martin has done his own research on the internet contradicting this, claiming that marital sex comforts dementia patients just as much as all the other things that are done for them without meaningful consent: food, shelter, medical care. Crucially, it comforts the carer, too. He loves his wife and this is a vital way to keep this alive.

Icily livid, Amanda calls the police, which sets in train events that she almost instantly regrets. Martin is prevented from seeing Leslie, who is terrified by the rape exam and whimperingly baffled as to why her husband is not there. The only way to suspend the legal action is for Leslie to go into a care home, which has long been Amanda’s demand. This is furiously resisted by Martin, who now sees all this as a malicious, dishonest way of forcing the situation on them both – it’s a care home, or it’s the cops – and a permanent stain on his character whatever the outcome. Meanwhile, Sara is developing a relationship with a boy at her new London school that her mother knows nothing about.

The story moves from one agonisingly difficult and ambiguous situation to the next – each a terrifying point of no return, each the awful occasion of things seen and said that can’t be unseen or unsaid. Is Amanda right to take the view that she has – or has she, in some crucial way, mishandled things? Is Martin an abuser of the most sinister and hateful kind, or misunderstood? Is the care home itself such a bad place? Even the crisis that this entails, connected to the unmentionable truths about older people’s sexuality and propensity to abuse, doesn’t exactly solve the question. Everything that happens, each station of the cross, each unbearable ordeal, is just a function of the overall situation, which can only be managed up to a point.

The crux of the film is a four-way conversation between a social worker, Amanda, Martin and Leslie. This involves Martin’s tearful, passionate declaration of love for his wife and best friend; a virtual reaffirmation of vows, which Leslie poignantly returns. Has dementia made her affirmation valueless? Queen at Sea is a film with a tragic, wintry candour.

7 hours ago

5

7 hours ago

5