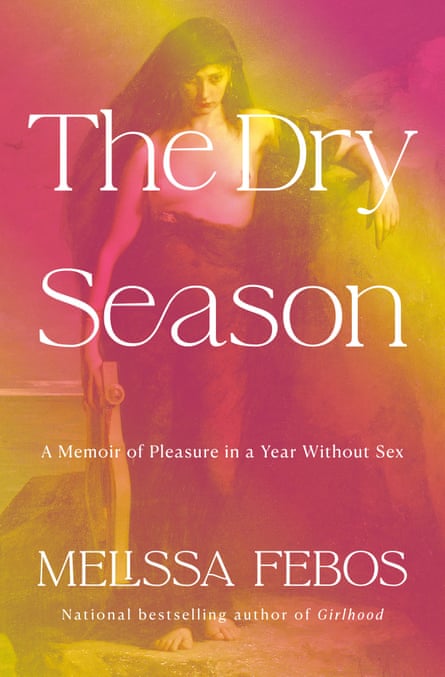

Febos’ life flourished while taking a year off sex and dating. In a new memoir, The Dry Season, the author explores the strong hold romance had on her

When Melissa Febos decided to be celibate for a year – after what she describes as a “ravaging vortex of a relationship” and “five other brief entanglements” – she felt “pretty self-conscious and kind of weird”. But other people’s reactions surprised her.

“I thought people were going to laugh at me or be like, that sounds boring, but so many people would lean in and either get this eager look on their face or this sort of dreadful look on their face, and they would say, ‘Oh, I think I should probably do that too,’” she says. “I had no idea how many people had been in relationships for their whole adult life.”

Febos, a professor at the University of Iowa and author of books about working as a dominatrix, young womanhood and writing, chronicles this celibate era in her new memoir, The Dry Season. “I had scrutinized my experience and self in many different areas, but in this area, I was fairly unexamined,” she says. “I didn’t have as much insight about that part of myself.”

The experience ended up affecting more than her reliance on love and sex. “All the other areas of my life began to flourish and feel really fulfilling and complete,” she says. ”I had kind of a honeymoon experience with myself, especially at the beginning, because I realized almost immediately that I enjoyed my own company profoundly, perhaps even more than I enjoyed the company of any other person.”

What were those first weeks of celibacy like? What was the hardest part?

At first, I wasn’t quite sure what my goal was, or what the conditions of my celibacy would be. I began with sex, because that seemed like the most obvious common denominator in my relationships. So I thought, I’ll take three months off. Within the first few weeks, I had the experience of flirting with someone, and I got a text from someone I’d been on a date with, and I identified very quickly the feeling of excitement and distraction that had been propelling me.

I almost immediately began questioning the parameters of my celibacy: I thought, oh, perhaps it’s not sex. Perhaps it’s this feeling of being taken out of myself and chasing a psychological high that I get out of not just sex, but all of the activity around romance, flirtation and seduction.

What made sex and relationships so appealing for you?

One factor is a collective derangement that we have around love and sex. We idealize this very temporary, superficial definition of love, which has to do mostly with the early stages of infatuation and is predicated upon not yet knowing the lover, and not yet being secure or safe. That’s a traditional sense of eros, of longing and uncertainty; it’s a very immature definition of love, and it’s not sustainable.

But it is the part of love that pop songs and movies and romance novels are obsessed with. I think we have a collectively problematic relationship to love and sex, and also a narrative about it – that it’s going to complete us, and it’s just about finding the right person and then everything’s going to fall into place.

In addition, I developed early, physically, and underwent a radical difference in the way I experienced being perceived by other people, particularly by boys or men. And I got this messaging, as lots of young girls do, that my primary power in life was to attract and appear lovable and desirable. That’s a very fraught place to be sourcing one’s self esteem, and I identified it early, at a time in life when I felt really disempowered.

I’ve learned, partly as a result of being celibate and talking about it, that this is really common.

In the book, you talk about distilling these internal beliefs to an idea of “if I’m not wanted, I will die”. You describe this concept as dramatic, but women constantly receive messages – from companies trying to sell us stuff, pop culture – that partnership is what women should aspire to the most.

Those ideas have roots that go back literal centuries, right? Women’s individual personal safety and survival did depend on our being appealing to potential partners, both physically and financially. And that was true for a lot longer than it hasn’t been literally true. I don’t know how we would eschew that idea within just the last few generations.

Why did you include historical examples of women who were also celibate, like the Belgian beguines, the 12th-century abbess Hildegard von Bingen and Shulamith Firestone, who called herself a political celibate?

A few weeks into celibacy, I started to realize I had a set of role models for love and romance that were quite outdated, whom I had adopted as a younger person who was interested in semiconsciously justifying my own choices in love. These were primarily women who were artistically prolific and fulfilled, but also very passionate and messy in their love lives, like Edna St Vincent Millay and Colette and Sappho. I realized, I’ve chosen these role models because I’m already like them. And now that I’m trying to change my ideals, I need new role models.

So I went about reading about women who were voluntarily celibate across global history, and ended up becoming obsessed with these women who seemed incredibly complete and fulfilled, and lived profoundly creative and spiritually centered lives that were also very political, very community oriented, that were interested in mutual aid and art making and collectivity.

About a month into celibacy, you found you had a lot of time for other things. You included a short list in the book that I thought was really funny: you cut your hair, donated a bunch of clothes and ran 45 miles.

All the adults I know are always complaining about not having enough time, and I, too, have been like that for most of my adult life. This amazing space opened up as soon as I stopped engaging in activities related to love and sex. Some were kind of superficial, like, I revamped my whole apartment. But also, I had this luxury of time to bring a new focus to my creative practice, to all of my other relationships, my friendships, my family relationships, my job.

I had so vastly underestimated the amount of time and energy that I spent devoted to love and sex and flirting or being on apps or spending time with a partner or thinking about a partner or a potential partner. There’s no way that I could have measured that while I was engaged with those things. I just hadn’t realized that I had been preoccupied by partners and dating and love and sex, almost all of the time.

Ultimately you were celibate for a year, but originally had set a goal of three months. Why did you decide to extend that period?

I started with three months because that is a familiar unit of measurement. I’m a sober addict, and three months is a typical amount of time to detox, psychologically. I also knew it would be unrealistic for me to try to commit to anything longer. And honestly, even though it might sound ridiculous to other people, three months was kind of a long time for me to abstain.

But when I got to the end, there was no question that I had barely begun. I was just starting to get a sense of the deeply entrenched patterns that I had been stuck in for years, and I knew that it would take much longer to undo them. I had gotten a break, but I had not fundamentally or constitutionally changed.

In the book, a friend makes fun of you – like, three months is actually not that long.

Yeah, there were a number of people who said that. It’s relative, right? To someone who has trouble getting into relationships, it’s absurd, but I had been incapable of doing that.

This book – as with you previous books about addiction and sex work – is honest and revealing. What is it like to write vulnerably about your life, and what do you get out of the process?

Well, fortunately, I am alone when I write. So I get to write in total privacy.

I think when people read a memoir, it feels as though the writer is speaking directly to them in real time. But actually the writer gets to sit alone for years with those words until I find exactly the way I want to communicate them. I also get to sit with those reflections long enough to make friends with them and to become comfortable with them. I would never publish the first words I wrote about those subjects.

For me, writing is a sort of integrating experience, of undoing shame, of becoming friends with experiences that at one time made me very uncomfortable or felt incredibly vulnerable. By the time a book is published, it doesn’t feel so vulnerable anymore. I actually feel quite comfortable with that material and excited to share it.

Writing about it and publishing it also connects me to a vast community of people, both living and dead, who have had similar experiences and have survived them. And being a part of that larger network and lineage is incredibly meaningful to me. It makes me feel strong and connected in experiences that once felt alienating.

There’s a great scene where you describe trying to teach a friend to flirt, and you realize you’ve honed that skill in response to various external pressures.

Before I was in graduate school, I worked in food service, and I located this as a training camp in seduction, because it is through social skills and a form of magnetism that I earned my living. The better I was at it, the bigger tips I earned. But I had never thought of that as connected to seduction.

Also because I had gotten so much of my self esteem from feeling lovable or appealing or attractive, it was just something that I was constantly practicing from quite a young age. In my early 20s, I worked as a professional dominatrix, and that was probably the realm in which it was most explicit, where my ability to conform to someone else’s romantic or sexual ideal was the extent that I earned my living. People told me what they wanted and I became it.

My current profession, in addition to writing, is teaching creative writing. I use those same skills in the classroom, but it feels much less manipulative or transactional, because what I’m doing is using my ability to hold someone else’s attention so that I can share with them my genuine love for a text or an art form or an artistic practice so that I can imbue them with that same passion for the subject.

You mentioned your sobriety earlier. Were there commonalities between sobriety and celibacy for you?

When I started the celibacy, one of the questions I brought was whether I could apply the rubric of addiction and recovery to my pattern in love and sex, because there were certainly compulsive elements. I was sort of hoping that I could classify it as a form of addiction, because I had had such success when recovering from other addictions, and I wanted a clear solution.

Unfortunately, it wasn’t that clear cut. I don’t identify as a love and sex addict, at least not exclusively. But there was a lot of overlap. I brought a lot of the wisdom and tools I had learned in recovery to this process, from abstinence to the practice of writing an inventory to gain insight into personal behavior, which I learned to do in recovery from drug addiction.

My experience of recovery is that it is not passive. My recovery and abstinence from addiction are contingent on my active participation, and it affects everything about the way that I live. And it is also contingent upon my honesty with myself, about my complicity, my past behaviors, and that also became incredibly relevant to my process of celibacy. Accountability cannot be skipped over at any process of personal change, and I learned that in sobriety.

Voluntary celibacy is a hot topic now, as with the 4B movement. What do you think has shifted culturally for that to happen?

I think certain groups of people are bringing more scrutiny to conventions that they have taken for granted or passively complied with. And one of the reasons is that the political landscape in the US has taken such a hard shift to the right. We’re living under an incredibly oppressive government. Part of this swing to the right is backlash against feminism and civil rights movements. People are responding to that with an equal force, both individually and collectively, and a part of that is scrutinizing how relationship dynamics are reinforcing institutional oppression.

You’re now married to your wife, whom you describe meeting in this book. Have you brought principles from that celibate year to the present era of your life?

I have redefined my ideal for romantic love as one that is not based on dependency. I think our fantasy of love has to do with need and dependency. My definition of love is contingent upon a very conscious choice to support the flourishing of another person. It’s based on choosing them, every moment that I maintain that connection. That is the only way I became qualified to have a long-term relationship. I would never have gotten married if I hadn’t redefined love in this way, because I think any other definition is not sustainable.

-

The Dry Season is out now through Knopf

1 day ago

9

1 day ago

9