Growing up in the 1960s, Joanne Briggs knew her father, Michael, wasn’t like other dads. Once a Nasa scientist, now a big pharma research director, he would regale her and her brother with the extraordinary highlights of his working life.

If he was to be believed, he had advised Stanley Kubrick on the making of 2001: A Space Odyssey, smuggled a gun and a microfiche over the Berlin Wall and, most amazingly, conducted an experiment on Mars that led to the discovery of an alien life form. This was in addition to earning a PhD from Cornell University in the US and a prestigious doctor of science award from the University of New Zealand. Quite a leap for the son of a typewriter repair man who grew up in Chadderton, a mill town on the road from Manchester to Oldham, before getting his first degree from the University of Liverpool.

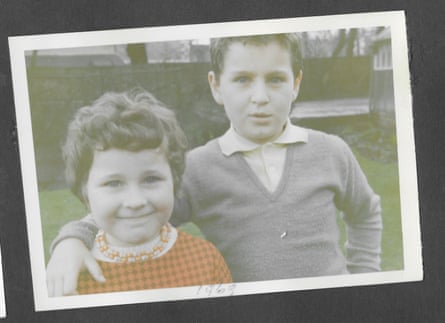

But when Joanne was seven, her father abruptly walked out on the family. He’d been married to her dressmaker mother Marion for 13 years when he decided to leave Britain and his job at the pharmaceutical company Schering and start a new life in Africa with a colleague. “From that point on, I told myself my father wasn’t really gone – he was just somewhere else. He was incredibly important and well known, a powerful thinker who had to be elsewhere to do that,” says Joanne from her home in Sussex. She is now 61, but with her mop of auburn curls and impish grin, it’s easy to imagine her as a child, dazzled by this larger-than-life character.

She describes him as a dapper figure, always dressed in a blazer and pressed slacks, aviator sunglasses enhancing his enigmatic air. “In one of these pictures I look like a little girl holding hands with an operative from MI5, after he’d been issued with a wife and child as part of an elaborate plan to conceal his identity.” The resemblance was to prove more accurate than she realised.

The illusion of a father who was not quite real was only intensified by the fact that, after he left, they would only see him fleetingly. “He would come to Europe once a year in order to go to the World Health Organization in Geneva. He’d whisk us off to London, to Harrods’ toy department, where I’d buy plush toys. We’d eat in fancy restaurants and I could order what I liked,” Joanne remembers. “After gorging on prawn cocktail and creme caramel for every meal, was it any wonder that these visits always ended with me being sick? Eat what you like for 24 hours, then nothing for 364 days. It was incredibly disruptive. After a while, when I was 11, I refused to go.”

In 1976, when Joanne was 13, Briggs was appointed professor of human biology at Australia’s newly opened Deakin University. She went to visit for a couple of summer holidays but then didn’t hear from him again until she was 22. “For reasons that were unclear, he had walked out of his job in Australia and moved to Spain.”

Then one day in 1986 she received a message saying he was back in the UK and wanted to meet her. He told her that a Sunday Times journalist had interviewed him for a story about his activities but described the potential scandal as a “misunderstanding, a pack of lies”, driven by the jealousy and competition of academic life.

With a wry smile, Joanne recalls the morning two days later when she was confronted with a photo of her father on the front pages of not just the Sunday Times but also the News of the World. The latter bore the headline “Bogus Boffin Is Unmasked”. “I don’t remember any kind of emotion, though my heart was racing as I read it,” she says. “I’d learned in childhood to step back from strong feelings around this unpredictable parent, to move away and watch.”

The Sunday Times exposé by Michael Deer revealed that Briggs had faked research assessing the possible risks of heart and arterial disease in women after prolonged use of the contraceptive pill. This research, Deer said, “was extensively relied on in drug company advertising to promote the pill’s safety claim”. Briggs, he added, had “admitted serious deceptions in his research”, which had been largely funded by two drug companies, Schering of West Germany, for which Briggs had once worked, and Wyeth of the United States. Schering and Wyeth both denied knowledge of the fraud, and said they would no longer use Briggs’s research. Other experts pointed out that medical advice about the safety of the pill wasn’t based solely on Briggs’s research but on a body of work that had reached similar conclusions.

Two months later, Joanne received a call informing her that her father had just died in Spain, a week after being hospitalised with delirium. “He was buried immediately, as per local custom. His wife was the only mourner at his funeral and the cause of his death is not recorded.”

Given her father’s history of deception, I have to ask: has she considered that he might still be alive? Fortunately, not much fazes her these days. “I recall a journalist contacted my brother and me as soon as the news broke, with a conspiracy theory that he was either in hiding or had been killed. This never got into the papers, but it stuck with me. Combined with the unexpected and strange nature of what had happened, from the Sunday Times in September to his apparent sudden death in November, the whole thing seemed to need another explanation. I think we both thought for a while he might not be dead or had come to harm related to the scandal. But these days I hardly ever think about the possibility, remote though it is, that my father didn’t die at all.”

One might sensibly assume that that was the end of the story. And, for the next 34 years, Joanne got on with her life, had a son and became a barrister. But this was far from the final chapter. “When we were all in lockdown in 2020, and looking for things to fill our time, I was reading the Cumberlege report,” she recalls. Officially known as the Independent Medicines and Medical Devices Safety Review, this looked at how the NHS had responded to women’s concerns about a number of medical treatments.

Now involved with the legal side of the detention and discharge of psychiatric patients, Joanne started reading the document for her job. “My interest was sodium valproate, a mood stabiliser included in the review. But then I read about this other drug, Primodos, a hormone-based pregnancy test.

“I’d never even heard of Primodos but it kept popping up,” says Joanne, “and to my astonishment so did my father’s name.” In 2014, she discovered, Yasmin Qureshi, MP for Bolton South and Walkden, had mentioned Briggs in a House of Commons debate about Primodos, which had been manufactured by his former employer Schering. She then stumbled upon a 1992 Nature journal paper, Reflections of a Whistle-blower by Jim Rossiter, who was head of the ethics committee at Deakin University and had been quoted in Deer’s Sunday Times article. “Rossiter was angry about the way he’d been treated by the institution. He accused my dad of being abusive and unpleasant – and, while he’s at it, he states that he doesn’t believe that my father had a doctorate from Cornell. He suggests that he had made it up, and probably the prestigious doctor of science award from New Zealand University as well.”

Joanne was intrigued. The red and blue theses were on a shelf in her brother’s study. “I thought: ‘This is easily provable.’” She contacted Cornell University, which did indeed have a publication by “Michael H Briggs, 1959” in its library. “But somehow, I felt I couldn’t just leave it at that. I contacted the librarian and asked for some screenshots of its pages. I suppose as a barrister I am used to proving things.”

The pictures were of a volume very similar to the one in the UK. Almost the same, but not quite. The library version, the real one, isn’t a PhD thesis at all – it’s labelled a master’s dissertation, one you’d write up at the end of a one-year course. And it has an account by her father of how he’d come to Cornell for a year to study for said MSc. He’d made the PhD up.

From this point on, everything started to unravel. Further investigations revealed that the doctor of science award was murky as well. Two eminent scientists had rejected Briggs’s application – but whether through an administrative oversight or someone acting in a more calculated fashion, somehow it still succeeded. Given that all this happened in the early 60s, the truth will probably never be known.

At this juncture, Joanne started telling her friends about everything she had uncovered. “I told them: ‘You know all those things I told you about my dad, the incredible scientist? Turns out he made the whole thing up.’ Many of them said I should write a book. When I had 8,000 words or so, I decided to enter the Bridport Memoir prize.” In 2022 she was named as the winner.

Now published, The Scientist Who Wasn’t There documents her father’s extraordinary career as a liar and fantasist, but also explores the impact his actions had on his family. “Writing the book gave me a much better understanding of my dad as a person than if I had not found out all these things about him. He would have remained a fantasy figure. I’d previously seen him as someone who moved ever upwards from job to job, opportunity to opportunity. Now I see it as a career of repeated flight, of him abruptly moving away from situations where he might get found out and towards lesser-known institutions who were grateful to have him. They thought he was marvellous because he told them he was – it’s a classic conman routine.”

Briggs did indeed work for Nasa, based at the California Institute of Technology. But Joanne believes the brevity of his sojourn there in 1962 holds the biggest mystery of all. “He was only there for a year, probably less. I think something must have gone very wrong because that was his fantasy job, he was working on Mars probes. They probably rumbled him.”

In 1963, shortly before Joanne was born, Briggs left Nasa and moved back to the UK to take up a research post at Analytical Labs, an animal feed laboratory in Wiltshire. It wasn’t an obvious move. “While researching the book, I looked into this mysterious lab and discovered it was known by another name at Companies House, and that it had never had any connection with agriculture whatsoever.” The company was based at Corsham, a Ministry of Defence base; when her father went to work there, this was also the home of the Central Government War Headquarters, the secret bunker intended to house the government in the event of nuclear war.

Is she suggesting that her father was in fact a spy? “I think of all the theories, it’s the one that hangs together most coherently,” she says. “He had extremely high security clearance because of his Nasa work. Why would you need that to work with animal feed?” In the book, she suggests that the animal feed work could have a link to the government’s plans for agricultural capacity after a nuclear attack. Then there’s the fact that a few years later, in 1966, Briggs suddenly went to work for Schering’s UK research department in the area of hormone research – totally unrelated to either Mars or animal feed. Schering was on the radar of intelligence agencies because unusually, it had bases in both East and West Germany.

How has all of this affected her? Joanne is delightful company with a dry sense of humour and, like her father, is a natural raconteur. “Growing up, there was a sense of almost romantic longing for my father. As an adult, well, I have never been able to watch films like Father of the Bride. I’ve never been able to tolerate dramas about fathers and daughters. I couldn’t face that loss, though I could probably watch one now. I’ve been married and divorced twice and I’m not currently married. So, my own ability to stay married may have been influenced by my past.”

Does she believe her father harmed people? “That is so, so hard to answer. If you look at him through the prism of fabrication and the identity that he’d created, he was not the scientist who he claimed to be. Would he have been able to make good decisions, or might he have allowed decisions to ride for a little bit too long? Would he have had the confidence to make difficult decisions and carry them out? He probably wasn’t the best choice to be a director at Schering, whatever they wanted him to do there. I think that’s about as far as I can go.”

Does she feel disappointed in him? She stops to think. “There’s a French expression, ‘Tout comprendre, c’est tout pardonner’, which means to know everything is to forgive everything. He was a man who grew up reading science fiction and got the idea that he could be a spaceman, that he could know all of science. And maybe he thought there were people at Oxford or Cambridge that might beat him to it. Maybe he thought he hadn’t the time to stand still and prove to everyone how clever he was – that he needed to fake it until he made it. And then he kind of forgot he was faking it.”

The Scientist Who Wasn’t There by Joanne Briggs is published by Ithaka (£20). To support the Guardian order your copy at guardianbookshop.com. Delivery charges may apply.

5 hours ago

4

5 hours ago

4