Watching the TV coverage of the conflict in Gaza with increasing dismay this week, my mind went back to the banks of the Suez canal in October 1973. I was filming the surrender of the entire Egyptian third army with a team from the BBC, without significant censorship or hindrance. The Israeli commander, Gen Avraham Adan, paused in whatever he was doing to give us an update.

Crossing the canal on the Israeli pontoon bridge in a bright yellow Hertz car (not a wise choice of colour) we were even helped when we had to repair a tyre that had been punctured by the shrapnel that littered the battlefield.

Censorship? Yes, the report was censored by the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) back at the satellite feed point in Herzliya. But the censorship was limited only to matters of operational security. This was obviously helpful to the journalists, but also to the Israelis themselves. They had independent verification, with video to back it, of their remarkable achievement in turning around their initial setbacks in Sinai. And they could show, through scenes with a biblical resonance, that the Egyptians’ surrender was conducted humanely and in accordance with the Geneva conventions, the laws of war. As the great columns of the third army mounted a sand dune, they exchanged their weapons for bottles of water abundantly provided.

Was it always this easy? Of course not. On another occasion, I rose early and reached a road block beyond Gaza only to be turned back, as all the press were that day, on the orders of southern command.

But that was exceptional. The IDF operated a policy of relatively open access based on mutual advantage. Sometimes it would herd everyone into press buses, which was far from satisfactory. But it would regularly provide the major TV networks with an escort officer, armed and in uniform, to enable and supervise the coverage. One of my escorts in the Yom Kippur war was Topol, the actor from Fiddler on the Roof. He was something of a hero in Israel, and all roadblocks opened to him.

On another occasion I was on my way to the Golan Heights, accompanied and with documents in order, when the great conductor and Israeli sympathiser Zubin Mehta asked for a lift. To my lasting regret I turned him down on the grounds that I had a press pass and he did not – I thought this may harm my chances of being allowed in.

Nowhere that the IDF operated was off limits to us. We could film what we wanted and freely interview soldiers of all ranks. In the trenches of the Golan Heights, because of language difficulties, the other ranks tended to be South African immigrants.

I was also free to make mistakes. In 1968, the year after the six-day war, I returned to Israel and interviewed the chief of staff, Gen Haim Bar-Lev, who was busy building the defensive line that bore his name. I travelled to Jerusalem and was stopped at a roadblock outside the biblical village of Emmaus. It stood at the centre of the Latrun salient, a Jordanian outpost in the previous war of 1948. The Israelis were busy dismantling it brick by brick. I was not allowed to film it and could only have reported it by leaving the country, not to return. Such compromises are commonplace, but I regret this one. The village disappeared, to be replaced by a Canadian peace park.

I was also allowed, after 1967, to visit and stay in Gaza, and show the day-to-day reprisals by the IDF against Palestinians whom it held responsible for previous attacks. The same applied to the destruction of homes in the West Bank city of Qalqilya, and the sowing of landmines round the churches of St John the Baptist in the Jordan valley. All of this passed the IDF’s censorship without difficulty.

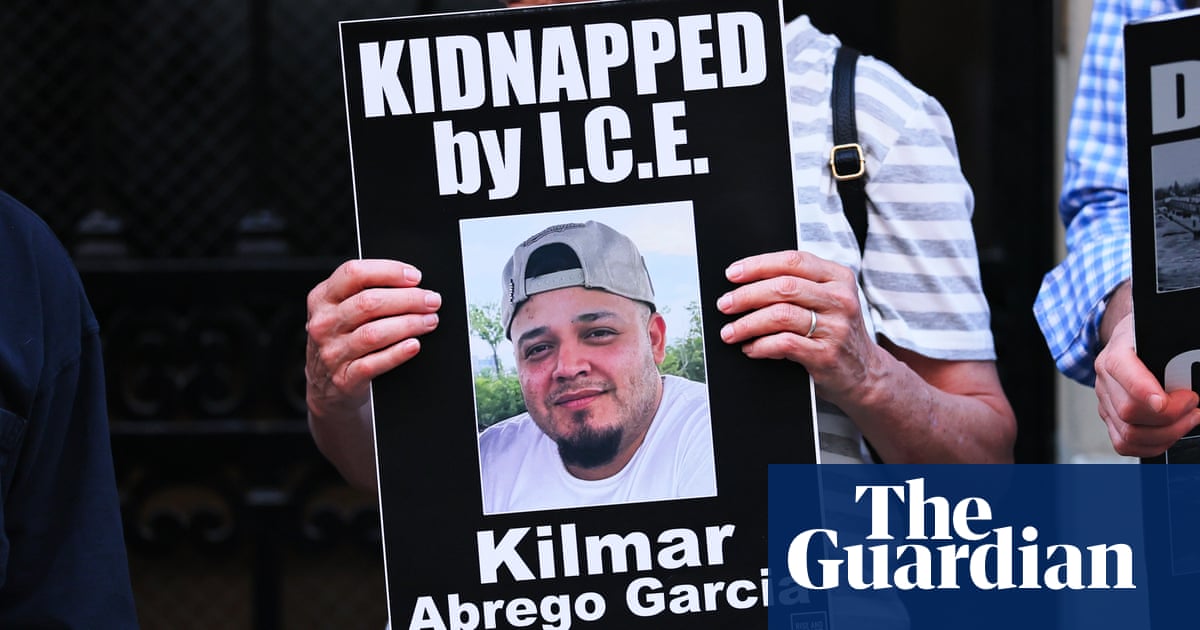

Fast forward to today, and the coverage – or rather, the non-coverage – of the conflict between the Israelis and Hamas in Gaza. The broadcasts regularly start with the mantra that the IDF does not allow foreign media access into the Gaza Strip, and proceed with the most vivid coverage, shot by brave freelances and other civilians posting on social media from inside Gaza, of scenes of death and destruction with the commentary voiced remotely in Jerusalem, Ashkelon or London. Often, both print and broadcast media preface the numbers of the dead and injured with a reminder that they were provided by the Hamas-run health ministry – sometimes the only source available.

My former colleague Jeremy Bowen said on the Today programme on Wednesday: “Israel doesn’t let us in because it’s doing things there … that they don’t want us to see, otherwise they would allow free reporting.” I’m inclined to agree with him.

My sympathies are with Bowen, Fergal Keane and others at the BBC, especially when Donald Trump flings around baseless accusations of bias. The BBC and other responsible news outlets have a difficult line to tread. I cannot speak for the American networks, but the British channels all have excellent reporters standing by in the region, not exactly there but thereabouts, sometimes on the high ground overlooking Gaza, which some reporters call the “hill of shame”. What is missing is the first-hand experience of the war, shared by reporters on the ground who can properly interpret what is happening. This gives free rein to rumour and falsehood.

What Bowen and I know from our shared experience is that it is not enough to win the war of weapons without also winning the war of words and images. And the IDF must see that it is losing. It has historically had its ups and downs with the foreign press, but nothing like the present entrenched hostility. It is doing itself great damage, which it is beginning to feel diplomatically.

I would urge the following: that the foreign press, especially the TV networks, continue to stand their ground, and that the Israeli press machine does itself a favour and relaxes the rules to allow some independent access to Gaza. This will not only limit the tides of propaganda (on both sides, it must be said) but perhaps hold the frontline troops to higher standards of behaviour, just as it did beside the Suez canal in 1973.

It is important to both sides to reestablish at least the limited level of trust that used to exist between them. Here is an example. In the 1973 war, we were able transmit the news by satellite on the day that it happened. Our office was a chair beneath a palm tree near the feed point. In the 1967 war, the exposed news film was bundled into onion bags – blue for the BBC, red for NBC – and taken to the censor who stamped his approval on the masking tape around the neck, before it was air-freighted to London. But he had to take our word for what the film actually showed.

The public had a more accurate account back then of events on the battlefield than it does today through the fog of war in Gaza. When access is denied, everyone loses. And, Israel, that includes you.

-

Martin Bell is a Unicef UK ambassador. He is a former broadcast war reporter, and was the independent MP for Tatton from 1997 to 2001

-

Do you have an opinion on the issues raised in this article? If you would like to submit a response of up to 300 words by email to be considered for publication in our letters section, please click here.

12 hours ago

6

12 hours ago

6