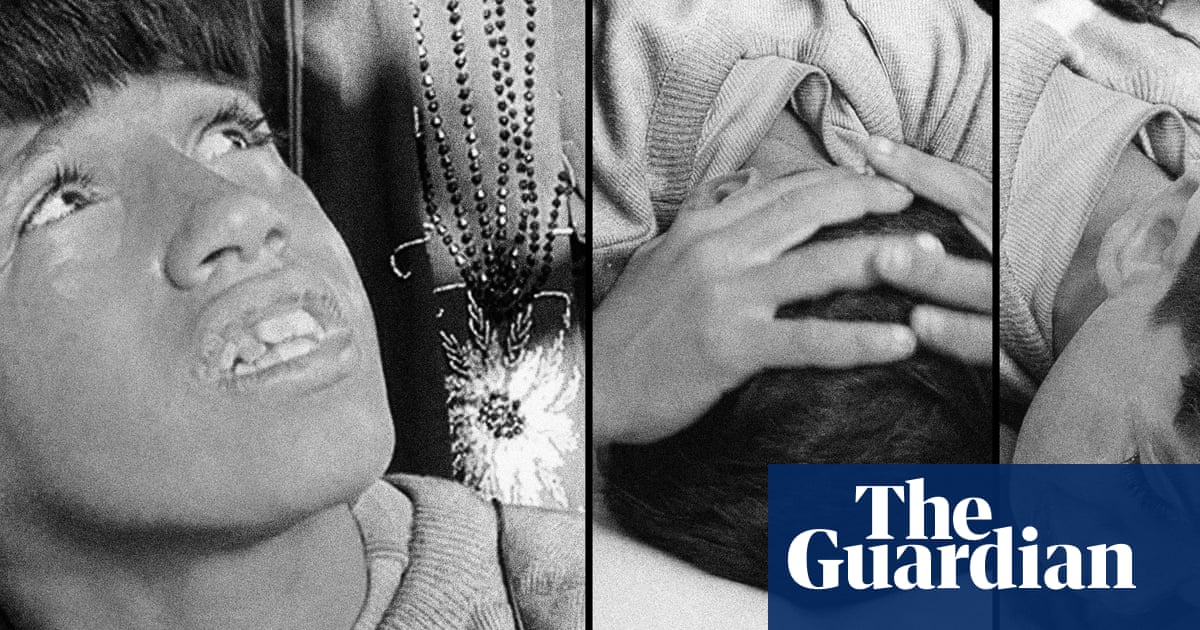

Outside a cafe three blocks from Arena Kombetare, two men stood on chairs and fastened attachments to the awning. Thursday lunchtime had just passed and Tirana was gearing up for a match that could have filled the national stadium at least 10 times over. There was no trouble identifying Albania’s flag, the double-headed black eagle spreading from its centre. The second banner being hoisted has become common currency too. It bore the word “Autochtonous”, presenting a version of the “Greater Albania” map that transformed a football match into a major diplomatic incident in 2014.

By Friday morning that flag had been replaced with its less incendiary alternative. Perhaps the authorities had popped in for a quiet word. They want to eliminate potential triggers for the kind of chaos that erupted in Belgrade 11 years ago, when a drone lowered the controversial image into Partizan Stadium during a European Championship qualifier between Serbia and Albania. The ramifications of that night stretched far beyond sport and there were sighs of relief when, the following November, a rematch in the provincial Albanian city of Elbasan passed without major incident.

Faces surely plunged into palms at both countries’ football associations last December, though, when they were drawn together in World Cup qualifying for 2026. Eyebrows were raised externally but there was nothing to prevent them meeting again: despite a long and bloody history whose freshest scars were inflicted during the war in largely ethnic Albanian Kosovo, the nations are not in active conflict. Neither had asked to be kept apart from the other. It was inevitable that the problem of navigating their relations around the football stadium would resurface one day.

No resources are being spared in solving it. About 2,000 police personnel will be deployed for the sides’ first Group K meeting on Saturday night, including special forces and counter-terrorism operatives. Additionally, sources suggest as many as 500 plainclothes officers will be situated among the 22,500 crowd. Away fans will be absent. Anti-drone equipment is being installed in the surrounding area and potential miscreants have been warned their devices will be shot out of the sky.

Presumably any planned disruption would take a different form; drones were not quite commonplace in public life when that tiny craft unleashed hell in Belgrade. But those measures revive memories of Ismail Morina, the bearded and outwardly harmless crane operator whose willingness to admit responsibility for the 2014 incident brought national hero status. Although not widely reported at the time, Morina had an accomplice who has since preferred to remain in the shadows.

Morina’s openness came at a cost: he was arrested before Serbia’s visit in 2015 for illegal possession of weapons, keeping him safely out of view for the game. Later he was imprisoned in Croatia and Italy, where he has residency, on a Serbian arrest warrant issued through Interpol. He has returned to Albanian stadiums, being held aloft in the Arena Kombetare stands at a match against Czech Republic in 2023 and exchanging shirts with the goalscorer Jasir Asani. Recently he has been seen at domestic games but, in the buildup to Saturday’s meeting, his previously active social media accounts have disappeared. If any of his old associates know where he is, they will not say. The assumption must be that he would not risk approaching the venue on Saturday.

He would not be the only ultra, past or present, who is kept away. The Albanian FA has not sold tickets en bloc to supporters’ groups, instead allocating them by random draw from more than 200,000 applications and hiking up prices. It appears a deliberate attempt to sanitise the atmosphere; the Tifozat Kuq e Zi group, which provides the most vibrant spectacle at national team games, responded furiously and pointed to an “organised farce” aimed at the wealthy. They will host an alternative gathering by the Pyramid of Tirana, 400 metres from the stadium, where permission has been granted for a big screen. Match ticket prices on an intensely active black market have exceeded £1,000 at the top end.

The fact Albania and Serbia will co-host the Uefa Under-21 Championship in 2027 adds another dimension. If the stakes are high for Saturday’s hosts, there is plenty riding on the occasion for European football’s governing body. Such an ambitious arrangement, driven largely by the Albania FA president and Uefa executive committee vice-president, Armand Duka, may appear untenable if anything goes wrong. Tifozat Kuq e Zi has expressed its views on the co-hosting by verbal and visual means; it senses this has contributed to its ostracisation.

The only distraction during Albania’s training session on Thursday evening was a set of zealously deployed sprinklers, their presence hardly unwelcome in temperatures touching 30C. Elseid Hysaj, the Lazio full-back, is the only squad member who played in the Belgrade fiasco. “We should not repeat the images of past years,” he said. “The coach has asked us not to panic about this match. We need calm and emotional balance.”

after newsletter promotion

Sylvinho, the manager in question and one of international football’s more affable characters, joked while playing keepy-uppy with his staff but is under pressure to deliver. The same can be said of Dragan Stojkovic, his opposite number. England, who complete the Group K quintet with Latvia and Andorra, are deemed near-certain group winners by both camps. Albania and Serbia know they are jostling for a playoff spot and that their meetings, the second of which takes place in four months, will be decisive.

At 1.40pm local time on Friday, Serbia’s players arrived at their hotel a mile to the west of Tirana’s city centre. Armed officers from RENEA, Albania’s anti-terrorism force, flanked two buses that had travelled from the airport under escort. The first step of a weekend-long operation had passed smoothly. Should that remain the case, perhaps the spectre of 14 October 2014 will finally begin to fade from view.

15 hours ago

6

15 hours ago

6