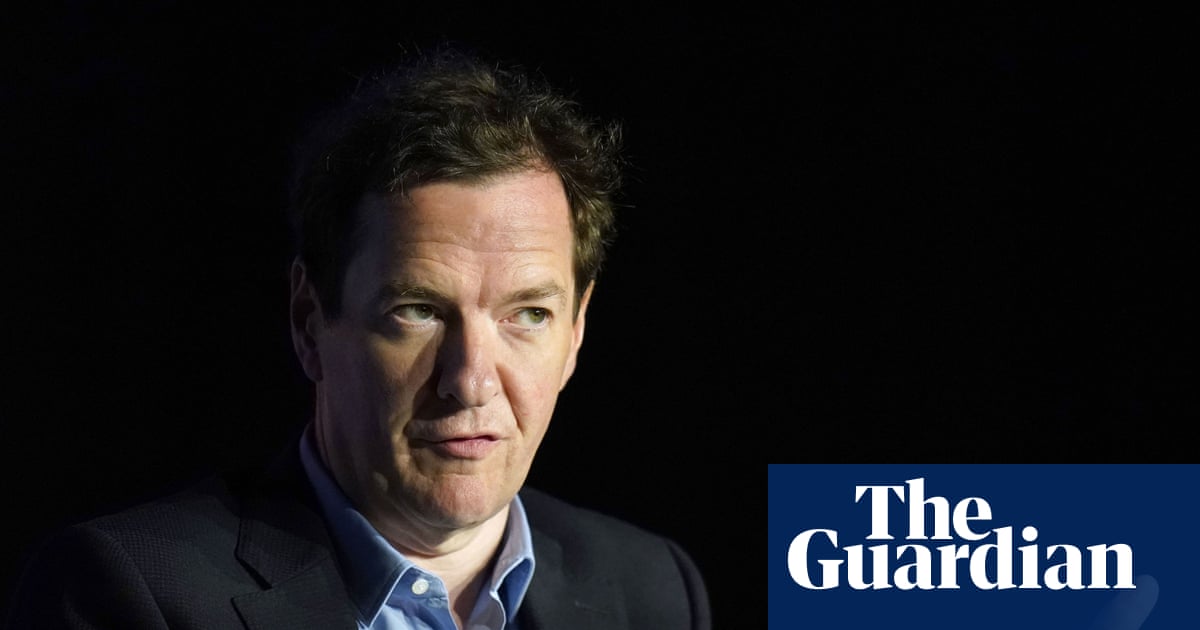

It’s a full-time gig being an Oscar nominee, what with the luncheons and fittings, the interviews and photocalls. It’s a wonder anyone ever gets any actual work done. “I’m tired,” says Amy Madigan, grinning crookedly on a video call. It’s noon in Los Angeles but the living room curtains behind her are shut tight. I worry she may have just pulled an all-nighter.

The last time Madigan was nominated was in 1985. She played Gene Hackman’s brittle daughter in a blue-collar drama called Twice in a Lifetime (the title now feels apt). Awards season, she points out, was shorter and sweeter back then. “Now it’s a big unruly beast. ‘We want to speak to Amy!’ I’ve been doing this since November. Do you not think people are sick of talking about us and seeing our faces? Haven’t you people seen enough?”

Madigan is now 75, which makes her the plucky veteran in this year’s best supporting actress race; the sentimental outsider, although there’s nothing remotely cosy about her. She is shortlisted for her role in Zach Cregger’s Weapons, a gripping small-town horror movie that plays out in segments, like a set of witness statements. Madigan crops up – first teasingly, then electrifyingly – as the nightmarish Aunt Gladys, the scariest child-catcher this side of Robert Helpmann in Chitty Chitty Bang Bang. Feeding off the young and conjuring adults into zombies, Gladys has round specs, clownish makeup and a brutal orange wig – and Cregger’s film has her tottering around town talking 19 to the dozen. The woman is laughable and pitiable right up until the moment when she’s not.

Those pulled drapes are unnerving. Madigan’s home looks so impersonal, like a bolthole or a safe house. That’s probably because it is, she explains. She’s in a rental she shares with the actor Ed Harris, her husband and longtime creative collaborator. The couple’s real house burned down in the wildfires last year. So that’s her other full-time job, sorting permits with the city. “We were hoping to start rebuilding in February or March, but that’s not going to happen. It’s going to take years.”

Cregger has credited Madigan with “saving” his movie. At the very least, she gives it a big injection of blood. And in the months since its release last August, Aunt Gladys has permeated the culture and become a TikTok sensation, beloved of costumed trick-or-treaters and professional drag acts alike. The actor steers clear of social media but is well aware of the fuss. “People like Gladys. They want to hang out with Gladys.” Stumped pause, crooked grin. “Which I find kind of interesting.”

Gladys’s appeal, sad to say, is not quite universal. I watched Weapons with my 11-year-old son and it scared him to bits. He refused to go to bed afterwards, thought Aunt Gladys might be lurking. That’s my fault as a parent but it is also hers, just a little. “Wow. Well, I’m sorry for doing that to him,” she says. “But I’m also taking it as a compliment.”

It’s a funny thing, horror. It somehow hits harder than more respectable genres. “Horror operates on an emotional level,” explains Madigan. “People want it and need it. They like to view it from afar. I grew up with all the genius black-and-white ones. Nosferatu, The Bride of Frankenstein, right up to Bette Davis in Whatever Happened to Baby Jane? That scared the hell out of me, though it’s maybe more gothic than horror. But it’s all based on the old fairytales. Someone stealing the children – that’s been around since ad infinitum.”

Gladys feeds on children, draining their energy to stay alive. Maybe Madigan, for her part, is now feeding on Gladys. For the past 10 years, her career has been on subsistence rations, with smaller parts in smaller films. So Weapons has been a godsend, if not quite a magic bullet. She is keen to keep things in perspective. “Friends are like, ‘Oh, the scripts must be flying into your mailbox.’ And I’m like, ‘No.’ But I’m more on the radar, more in the conversation, which is nice. It’s like Gladys showed up, made an impact and reminded the world I’m still here.”

How bad did it get? Did she ever think about quitting? “Sure. How could you not? Those thoughts invade, especially when you have a fallow time, and I’ve certainly had those during these past few years. Then you have a down day and think, ‘Will I ever get a job again? Maybe I’ve retired and haven’t really told myself yet.’” She pulls a face. “The business is brutal. It just is. But the reality is that I still love doing it.”

Evidence suggests she has always been a scrapper, a survivor, regarded as too tough and too caustic for mainstream Hollywood tastes. “Freckled, plain but winning,” wrote the critic Stanley Kauffmann of her first screen performance – she played a pregnant convict in 1982’s Love Child – with the implication that every subsequent triumph would come in the face of steep odds. So she made hay on the margins, playing John Candy’s girlfriend in Uncle Buck and Kevin Costner’s wife in Field of Dreams before picking up a Golden Globe for her starring role in Roe vs Wade, the 1989 abortion rights legal drama.

For a spell, she and Harris were an indie-film power couple, working off the same page, with their careers in parallel. Then his work-rate kept motoring – with roles in the likes of The Truman Show, Darren Aronofsky’s Mother! and Top Gun: Maverick – while hers began to trail off. Plus ça change. There’s an inbuilt sexism, she says, to the whole casting process. “But Ed knows the business as well as I do. So he’s good on all that. We met working together. We’ve done many films together. So we’re used to having each other’s backs.”

I’ve been meaning to ask about their appearance at the 1999 Oscars, when the director Elia Kazan was presented with an honorary award by Martin Scorsese and Robert De Niro. Madigan and Harris have collaborated on 11 films altogether, but that night was surely their most high-profile joint performance, as they watched the presentation silent, stony-faced and unclapping. Kazan was the great leftist film-maker of postwar US cinema, the man behind Viva Zapata!, On the Waterfront and A Face in the Crowd. But in 1952, he broke ranks and spilled names in front of the House Un-American Activities Committee. It was a dark time; lives were ruined. And Kazan, Madigan feels, played a role in all that.

“My dad was a journalist,” she says by way of explanation. “He was also the political liaison officer for the supreme court in Illinois. So I grew up politically minded. My dad covered the McCarthy hearings and it affected him greatly, to the point where he couldn’t really talk about it. So there was no way I was going to join in the applause. Maybe I don’t have that twist in my head where I think, ‘Oh, let’s forgive and forget.’ No, I don’t forget those kind of things. I don’t wish for that person to fall down a sewer – well, sometimes I do – but I don’t have to participate. And I thought it was shameful of the Academy to honour him in that way.”

Besides, her refusal wasn’t a comment on Kazan’s work – it was a judgment on his actions. “That’s right,” she says. “Although I don’t really agree with the idea that you can separate the two. There are certain lines you don’t cross.”

The trouble, of course, is that history repeats itself. Lines that are crossed tend to be crossed again. Just look at the political landscape today, she says. The near-daily assault on the first amendment; the footage of people shot dead in the street. She is furious about Trump and despairs at the state of the country. When their house burned down, she and Harris briefly discussed getting out altogether. “It feels awful – politically speaking – to be living in the US now. So of course the subject comes up in conversation. But I’m still proud to be an American. I believe in my fellow man. And you can feel something happening in southern California. People are terrified but they are also angry. They’re resisting, fighting back. So I’m guardedly hopeful.”

It is a strange time to have another date at the Oscars, she knows. She has no idea if she’ll win, the whole thing is a mystery. All the same, the nomination feels like a nice thing to have happened, especially after a 40-year gap. She’s viewing it as a belated reward for decades of hard graft, or even – dare one say it – as an honorary award of her own. “And that’s an unusual feeling,” she says. “That’s going to take some getting used to. I mean, it’s crazy how people are responding to Gladys. But I have to accept that they’re also responding to me.”

6 hours ago

5

6 hours ago

5