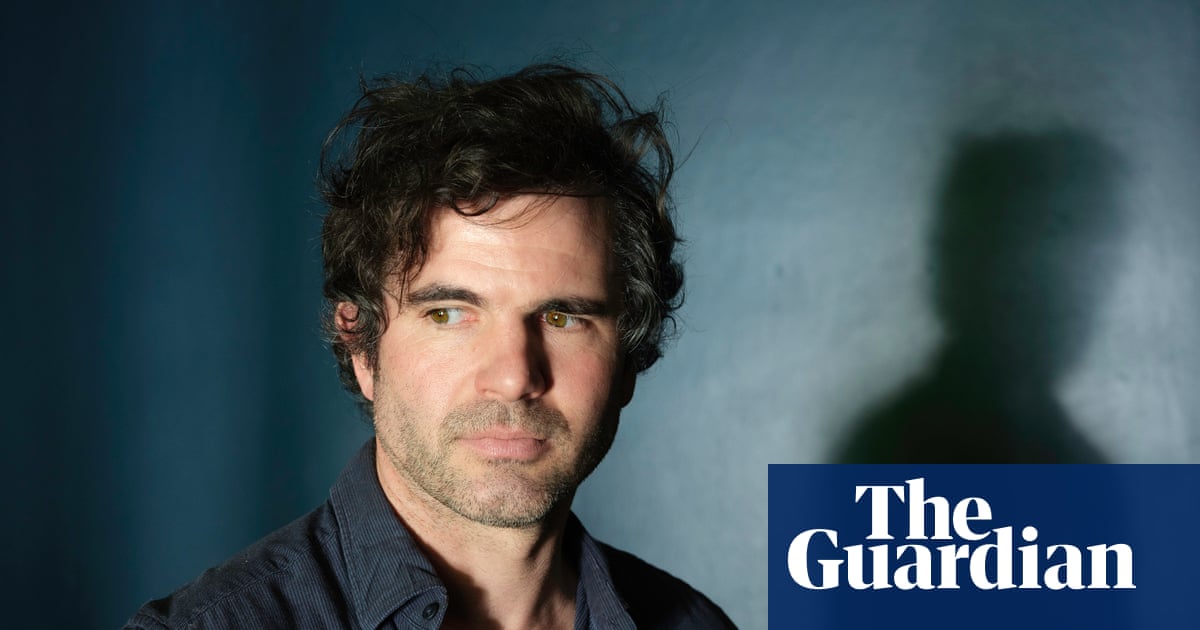

‘If cinema was a 19th-century dream actualised in the 20th century through chemistry, then the auteur was a 20th-century dream that needs to be actualised in the 21st through digital.” Canadian experimentalist Isiah Medina is hellbent on that task in his latest feature, which almost entirely comprises a troupe of po-faced cineastes declaiming such theory-freighted slogans, and bemoaning what dogs the genuine auteur these days: western-centric power hierarchies, industry racism, the economic exclusion of serious artistic work, the tyranny of language.

It’s dense stuff, and staged at an ironic, if not quite playful, remove. Mark Bacolcol plays Clem, a director struggling to finance his next feature in the face of the system. Boyfriend Ez (Kalil Haddad) is an unblinking ideologue, who peps Clem up by telling him: “Be proud: regardless of race, most people don’t like your work.” Collaborators Nico (Jonalyn Aguilar) and March (Charlotte Zhang) are struggling to hurdle the same structural obstacles. A hipster collage in his office juxtaposes Mao’s Cultural Revolution with the title of Armond White’s 2020 book Make Spielberg Great Again. Needless to say it’s not the great white hope Clem is holding out for.

There are flare-ups of self-awareness, or at least pre-emptiveness. “Now I’ve found out that the way my characters talk isn’t human,” says Clem. “Why is it we’re afraid of appearing inhuman?” Not a question that seems to bother the aggressively high-minded Medina, though it’s difficult to know how tongue-in-cheek this (presumably) auto-portrait is. It doesn’t seem to qualify as satire, or even psychological candour; rather, a burst of self-referential chaff to throw off anyone with conventional narrative expectations.

On that score, Medina cuts deepest via aesthetics. As they are taking place, conversations blink between different viewpoints, almost cubist-style; as well as in and out of adjacent scenes, or reveries. (As Clem says: “Thinking is being.”) Often, it feels strikingly radical, a fresh vocabulary of dis-establishing shots to counteract dominant points of view; but occasionally, as pretentious as the slam poetry scene in 22 Jump Street. Clem is beset by someone leaking his films, possibly a supercilious writer (Erik Berg), but you get the feeling Medina appreciates this chaotic gesture. “I’ve always felt that if you’ve never felt the desire to destroy your books, then you’ve never really read them,” the vexed director says near the start. This wilfully alienating but still-ingratiating cine-manifesto deserves close reading and exasperated sighs in equal measure.

3 hours ago

3

3 hours ago

3