If you were doubting that Nigel Farage had a serious chance of heading a hard-right British government in 2029, the people of Hamilton, Larkhall and Stonehouse just poured a bucket of particularly icy water over your head. Though Labour won the Scottish parliamentary byelection, defying predictions it would be beaten into third place, Reform UK chalked up more than a quarter of the vote – trailing the victors by an unsubstantial 1,500 voters.

This tells a devastating story. Nigel Farage’s outfit seriously outperformed the level of support indicated by Scottish polling: the last four surveys had Reform on between 12% and 19%, yet it secured 26% of the vote after standing here for the first time. This suggests it is mobilising previous non-voters whom pollsters are not picking up. The latest UK-wide YouGov poll, which asked people how they would vote if there were a general election tomorrow, put Reform in first place, eight points ahead of Labour. Imagine if that polling in fact underestimates their reach.

There is, however, an important caveat. The multimillionaire businessman Zia Yusuf did an impressive job as Reform’s chair in professionalising its operations: his resignation speaks to a perennial threat of internal chaos. Like Ukip, Reform may be hobbled by its excessive dependence on its frontman.

The SNP, meanwhile, has ruled Holyrood for nearly two decades in an age in which most incumbents are clobbered. The party has lost its best asset, Nicola Sturgeon. Even so, it did not expect to lose 17 points in this byelection. Its activists are divided on whether this loss is down to the party soft-pedalling on the independence cause, or failing to address voters’ bread-and-butter concerns. It seems almost certain that it suffered the opposite phenomenon to Reform: its demotivated supporters stayed at home.

The byelection offered up yet more striking evidence that the Tories are being replaced as the standard bearers of the right, as they bagged a paltry 6% of the vote. This is the end stage of a process kickstarted by David Cameron in 2010: try to placate the right of his own party by throwing them endless red meat, making them fatter and hungrier. It’s the same phenomenon that is unfolding across the west: the old centre-right is dying, and being replaced by a radical right that is increasingly contemptuous of democratic norms.

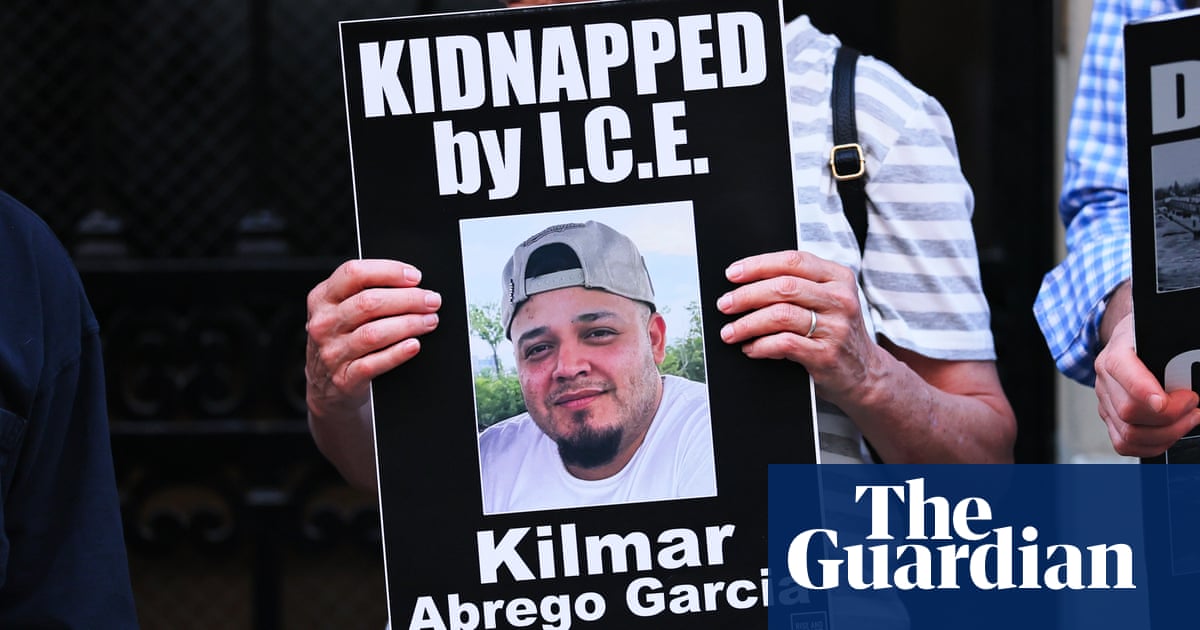

Given Reform’s racist claim that the Scottish Labour leader, Anas Sarwar, would “prioritise the Pakistani community”, its defeat is hardly reassuring, as it still finds popular support among hardcore Scottish unionists. As the pre-eminent psephologist John Curtice notes, Labour was in fact down on its already weak 2021 performance in this seat, triumphing only because of the fragmentation of the electorate. The result shows Labour is not on course to retake the seat of Scottish power, he concludes. The big message, he says, is that if Farageism is making inroads even in Scotland, its strength has been underestimated.

What next? Starmer’s foot soldiers have a strategy. Having achieved unparalleled unpopularity by attacking state provision for disabled people and elderly people, they are opting for a “squeeze” message. They believe Farage replacing the Tories is beneficial, because he has a lower ceiling of support than the traditional party of the right. Our electoral system will force voters to make a binary choice between a Labour government they strongly dislike, and a Farage premiership most fear. The choice is between two bad options – and they’re hoping that voters will pick the least worse.

Cast your mind back to the decision of Hillary Clinton’s team to intentionally promote Donald Trump as the Republican standard-bearer for much the same reason. That didn’t go well. Labour must surely understand how Farage’s capacity to enthuse non-voters raises the ceiling to an unpredictable height. Starmer’s team clearly looks to Canada, where an incumbent liberal government was on course for electoral meltdown, until progressives abandoned the leftwing New Democrats to prevent the hard-right Conservatives triumphing. Yet there are key differences. One is the small factor of the US president openly planning to annex their country. Another is that although Justin Trudeau’s administration may have been deeply disappointing from a progressive perspective, it did not ceaselessly alienate its natural supporters, as Labour has done, including by adopting rhetoric on immigration associated with the far right.

Labour won about two-thirds of the seats in the general election with only one-third of the overall vote share. Surely it recognises that Reform could do the same. This ability is only entrenched by our first past the post electoral system, which even the former Conservative minister Tobias Ellwood has described as “dated and unrepresentative”. Faced with a choice between lesser evils, the strategy for progressives ought to be clear: cement a pact between the Green party and other leftwing candidates, focus on 50 or so seats, and throw every resource at them. In a resulting hung parliament, they could force an end to this antiquated electoral system.

But the central belt of Scotland just underlined an important lesson. The west is in crisis: the rise of the radical right is both a symptom and an accelerant, and nowhere is immune.

-

Owen Jones is a Guardian columnist

12 hours ago

4

12 hours ago

4