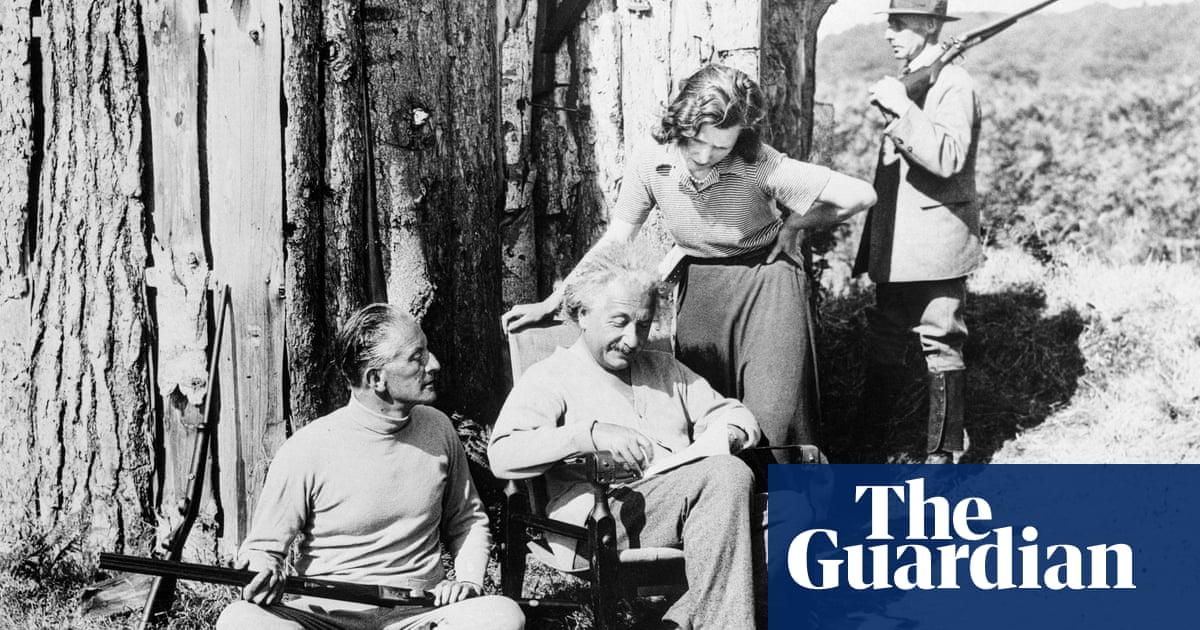

A winter’s day. My father in the dark room of my memory developing photographs. The door is shut. My sister stands with him. He aims to teach her the essentials of photography. How to turn a black and white negative rolled from the interior of his camera, unspooled in the dark, then bathed in trays of chemicals, to bring the past back to life in black and white.

My sister’s special treatment as the only one of nine siblings to learn this skill does not go unnoticed, by me at least. I am 10 years old and long to learn, even as I want only to be an insect in the corner watching unseen.

My father taught me fear. Small children rely on their parents for sustenance and survival and when a parent is abusive, where the only love a child comes to know is corrupted, it comes with a sense that other siblings, who also seek his love, are rivals.

Writing about child sexual abuse is hard. Writing about the unfathomable, yet surprisingly common jealousy experienced as the sibling of an abused child is even harder. This is what I aim to do here.

The pecking order of people in my family fascinated me from when I sat perched on a bench at the kitchen table. We dangled our legs and looked at our plates still empty until our mother piled on a mountain of potatoes mashed with carrot and onion. Hutspot, a Dutch delight designed to fill empty bellies with basic nutrition and as easy to assemble as cheese on toast.

Look around this table. Note the parents at either end. Mother closest to the kitchen sink, father at the head. A constellation that speaks to the order of things. Migrants to Australia from Europe after the war.

Imagine this family and consider which of these children suffers most. Is it the girl who sits beside me? At nine years old she travelled alone in an ambulance to the Fairfield infectious diseases hospital and stayed there for three months in the women’s dormitory with rheumatic fever, a strep throat gone wrong. Excluded with a communicable disease.

Or could it be her taller brother on the other side of the table? Months earlier as a sixteen-year-old he copped the same fate. Only his rheumatic fever morphed into osteomyelitis after the infection travelled from his heart to his feet. He nearly lost a leg, but doctors dragged his life and limb back from the brink. Still functional, despite the crater in its centre.

Was it the boy on the other side of me? The one christened the family genius, who scooped prizes in his final years at school, in Latin, French, English, mathematics, physics and chemistry. He was left-handed in the days when left-handedness was a curse to be ironed out.

Or the other boy on the bench, the “runt of the litter” because, unlike his four brothers, he failed to grow tall. He struggled to read in a family that valued literacy. He sat at the end of the table after dinner alone reading out loud. Each time he stumbled his father rapped a fork over his knuckles.

None of these. From the oldest to the youngest, the one singled out for the prize of victim, goes to my eldest sister. She in the dark room. A red globe overhead, the only light as my father touched her body in secret. It took 50 years before she could tell me.

How could I be jealous of an elder sister for having something I never wanted and yet at the same time longed for? My father’s abusive “love” and my mother’s apparent gratitude towards her for enduring it.

When Haruki Murakami’s character Kafka, in his novel, Kafka on the Shore, experiences a stab of jealousy, Murakami reminds us, jealousy is like “a brush fire. It torches your heart”. Heat that rises from your core. If there is any emotion that dogs me beyond shame and occasional deep longing, it is jealousy. And to understand this complex emotion I join with another who has researched this area for a deep dive.

We met online. Social worker Anais Cadieux Van Vliet had read my book, The Art of Disappearing and was interested to discuss the impact of childhood sexual abuse on what they call non-abused and non-abuser siblings. Cadieux Van Vliet uses the term with reservations, as it fails to include the fact such siblings are also indirectly abused. As part of their research, Cadieux Van Vliet has interviewed clinicians to ascertain how they consider the experience for non-abused, non-abuser siblings within such families.

Although clinicians might understand the vexed position we so-called non-abused siblings find ourselves in, others are more circumspect. Maybe more concrete in their understanding. As if the abuse matters only to the people within the abused/abusive couple, primarily the victim/survivor. The rest becomes collateral.

One of the hardest things to understand, the extent to which a person who survives abuse by avoiding it, one who sits beside or witnesses the abuse like me, or who like Cadieux Van Vliet learns about it later, carries a question: ‘What about me?’ A tingling of jealously we find hard to understand because we know we’re also the lucky ones to have been spared.

My father never showed me love. He had eyes only for my big sister – she was the one who got “special treatment”. Although she and I did not talk about it until I was in my fifties, I knew what had happened between my father and my sister even as a 10-year-old when we shared a bedroom. I had no words for it then.

How can we call abuse “special treatment”? In the mind of a child this is how it seems. Your father chooses you, or at least he chooses your body on which to focus his attention.

As Maurice Whelan, a psychoanalyst describes it, for the abused child a deep confusion ensues. The father visits in the night, in secrecy and does things with their body that trouble, and disturb them, even as this touch might arouse them in ways they cannot understand. Then the father swears them to secrecy and in the morning and in days to come, says nothing.

The non-abused sibling may not be aware of this. May not see it happening, as I did, but all non-abused siblings live in a hot house of repressed sexuality. It erupts in secrecy and silence in the shadows. A sexuality that is confused with power and shame.

My younger sisters have different stories. They too came close to being sexually abused by our father. Non-abused siblings, whether they consciously know or not, are overtaken by an atmosphere of secrecy and violent underpinnings that speak to something dangerous going on. It does not feel safe in such a household. The unspoken rule is to stay silent.

When I was 14, my sister told me the so-called facts of life as relayed to her by our father. He had given her this information to help her grow, he said, because our mother came from a repressed Catholic household and did not know what a man needed. He therefore taught my sister about his desire, confused as hers. And she in turn, wanting to shield me from the pain of his lessons, told me repeatedly: “If he touches you, scream.”

Layers of jealousy

When you’re a child, the life you lead is the only one you know. You catch glimpses of other people’s lives from a distance. Our family was unique in our foreignness and in the abuses my father meted out. It shamed me when I looked at the fathers of other children at my school who seemed more loving.

My father’s choice was my fault. If I behaved in a different way, if I was more like my elder sister, if I offered him more by way of interest, or body shape or beauty then he might not only notice me but also he might be kind and not fly into rages at the simplest slight. My mother’s overcooked steak. Dishes piled high in the sink. Any child who did not behave as they were told.

When I was 12 and shared a room with my elder sister I went to bed ahead of her. Alone under the blankets I imagined myself as Maid Marion from Robin Hood and his merry men. I hid in the forest terrified the Sheriff of Nottingham might carry me to his castle and ravage me. Somewhere in my unconscious mind, I knew what was happening to my sister.

I was almost asleep to the soft thud of my father’s bare feet on the carpet between our beds. My sister asleep or so I imagined. I did not want him to take me in his arms and possess me. I did not want whatever it was my father did to my sister on those nights, night after night when he came into our room while the rest of the house slept. And yet, I wanted to turn him into Robin Hood. I wanted my father to want me.

Looking back, it was as if any woman who commanded my father’s attention was one who evoked sexual feelings in him. The rest of us were dispatched. People to cook and clean. My mother bore babies for him, but those already born were of no consequence. Except my sister.

My mother believed our father had stopped visiting her in the night. She caught him once in our bedroom, my father hunched over my sister while I was in the next bed pretending to be asleep. “If you ever come here again,” she said, “I’ll kill you”. Her threat did not stop him, but my mother could not bear to believe otherwise. When you’re desperate, you’ll do anything to survive.

I was in awe of my sister’s courage when she stood in front of my father’s chair and sometimes asked for money. I could not ask for anything of my father beyond the good night gesture my mother forced on to us younger children. My father stretching up from his chair to make the sign of the cross on our foreheads as some type of fatherly protection.

I despised this ritual. The rasp of my father’s fingers on my soft forehead, the croak of his words, “goedenacht”, the air puffing back into his seat when he flopped down, and we, my younger sister and I retreated to our respective rooms, ready for the dangers of the night.

On jealousy, the colour green

Bless me father for I have sinned against my younger sister for wanting what was hers. I borrowed her dress when she did not give me permission. Then I ruined it. My sister’s dress was too small. I slipped into it well enough, but the buttons could not hold against the pressure of my first attempts to skate around the ice rink at St Moritz in St Kilda with school friends one summer holiday.

I came home in the dress; its underarms ripped from their sockets. My sister was enraged. I had destroyed her favourite dress. Blue denim with buttons up the front.

Jealousy ruins things. Ruins people. But my therapist reassured me it was a feeling, and not evil, however painful. It’s bad enough to endure this feeling, she told me, but ten times worse if you’re given the message it’s wrong to feel it in the first place.

If we squash the feeling because we believe it’s wrong then the feeling will bury itself inside, until the sinews of our hearts are like shards of stone that can harden into volcanic rock.

Explosions are dangerous. They can destroy everything in their path. Better to feel the tug and pull and pain of jealousy than to let it enter the vaults of the hidden and forgotten.

My father in the dark room of my memory holds my sister close and I shudder, relieved to be spared while sad to have missed out. Only in writing can I reconcile these two opposing emotions.

When you know something is wrong it surrounds you every day. In families where child sexual abuse occurs, not only are you silenced in the childhood of your home, you’re silenced throughout your lifetime, because it hurts other people to hear. But on the page, we can see it, the marks of memory. The open secret. The weird jealousy of an unloved child. The colour green.

3 hours ago

2

3 hours ago

2