Harris Dickinson makes a terrifically impressive debut here as a writer-director with this smart, thoughtful, compassionate picture about homelessness – engaging and sympathetically acted and layered with genuinely funny moments, mysterious and hallucinatory setpiece sequences and challengingly incorrect thoughts about the haves who fear the contagious risk of coming into contact with the have-nots.

Frank Dillane is Mike, a guy who has spent five years living on the streets in London: begging, stealing, eating at charity food trucks. Dillane’s performance shows Mike’s nervy, twitchy, live wire mannerisms have been cultivated over what feels like a lifetime of abandonment: he has a kind of suppressed pleading quality as he asks passers by for the “spare change” that fewer people carry in these post-covid times; his open smile has a learned survivalist determination only - what he is is not exactly charm, he is slippery and unreliable, but also intelligent and heartbreakingly vulnerable.

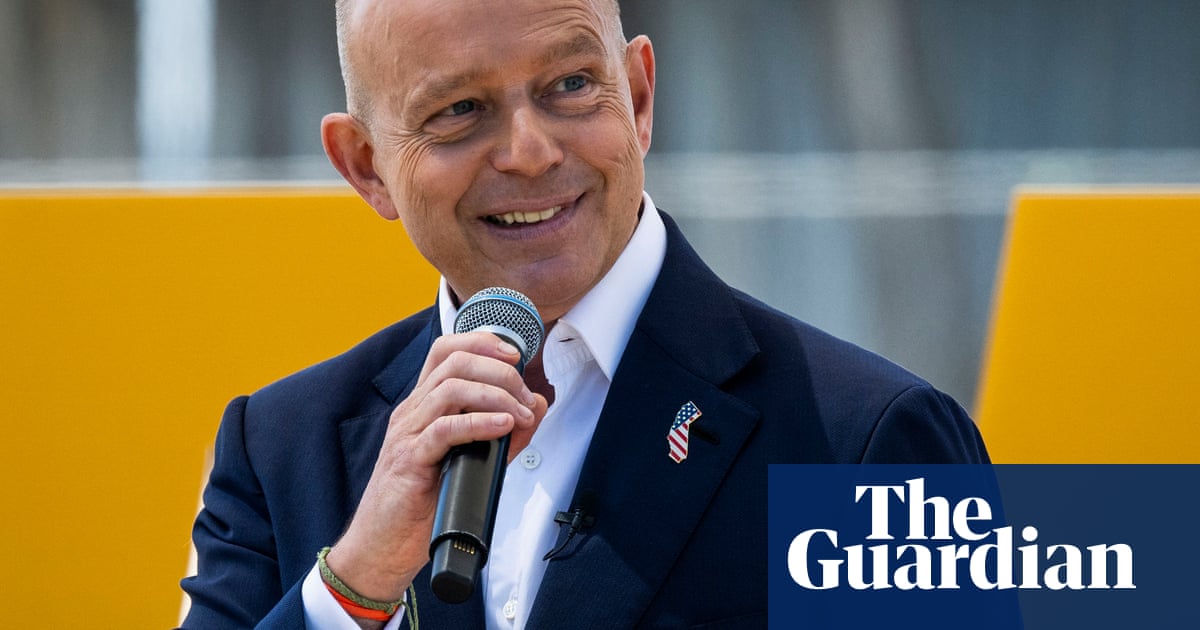

His one non-friend on the street is Nathan (played in cameo by Harris Dickinson himself) who steals Mike’s money which fatefully leads Mike to a despicable act of theft and violence for which he is entirely unrepentant and which leads to a prison sentence and a hostel place, a hotel kitchen job a period of sobriety on release in which it seems as if he is turning his life around, dreamily lost in his meditation takes and even buying a little present for his probation supervisor – to whom he also confides his plans to start a luxury chauffeur business.

But, very disturbingly, it seems possible that what undermines Mike’s fresh start is his restorative justice session with his victim, an encounter which is supposed to be healing and cathartic but which Mike has no idea how to approach. Dickinson shows that he simply doesn’t understand the new register of emotional intelligence now expected of him. Amusingly he objects to the session’s convenor’s breathy, patronising voice and singularly fails to apologise.

But he clearly is, at some level, aware that he has failed a test, failed at being a good person. His job at the hotel kitchen goes south and his new job picking up littler is uncertain, despite a new relationship with a woman working alongside him (a smart performance from Megan Northam) who is much closer to sorting her life out than him. Mike has good mates in the litter-picking job and good mates in the hotel kitchen job.

But it is one of the pickers that offers him some ketamine and things spiral inevitably downwards from there. Did drug addiction mean things were always hopeless, whatever resources his Mike’s personality might have offered, The film does not offer easy answers or answers of any sort.

When it looked as if Mike on the way up or on the way out, he avoided his old acquaintances: when he sees the appalling Nathan in a charity shop, he scurried out. The old ways were contagious. His old life was contagion. But did he get infected by the restorative justice session, which confronted him with evidence of his selfish aggression, evidence which triggered only resentment?

And all the time his plagued with vision-memories of a reproachful woman (his mother?) and a huge mossy, beautiful cave (some fantasy? childhood holiday?) These are the visions of a complex past and a compromised future.

4 hours ago

6

4 hours ago

6