Donald Trump’s followers, and the conspiracist influencers turned-government officials through whom he persuades them, have turned on the president and US attorney general after they declared an end to federal inquiries into Jeffrey Epstein’s death. But it would be a mistake to think that the investigation scandal is sui generis. It’s more like the culmination of a long-running trend, one in which Trump’s exploitation of the conspiracist fictions, distrust of institutions, and prurient fascinations of his base have finally come back to bite him.

A pedophile ring at the center of power is a recurring theme in rightwing conspiracy theories of the Trump era. During the 2016 presidential election, supporters of Trump, then an outsider challenger for the Republican nomination, began to spread dark claims about his rival for the presidency, Hillary Clinton. Online, far-right trolls and members of the population now called “low trust voters”– people who believe that something nefarious and conspiratorial is going on in the halls of American power, even if they don’t know exactly what – speculated that Clinton was at the head of a massive human trafficking and pedophilic abuse ring based inside Comet Ping Pong, a pizza restaurant in Washington DC. There was no secret ring. But that didn’t stop a disturbed man from showing up with a gun.

Pizzagate, as it was called, gave way to QAnon, the elaborate mass delirium in which Trump supporters believed that they were receiving secret messages from Q, a fictitious but supposedly highly placed security official. QAnon, too, centered around the notion that powerful people – Democrats, mostly, but also some Hollywood celebrities – were secretly running a massive pedophile network. In his dispatches, Q detailed Trump’s efforts to dismantle a deep state ring of child sex trafficking. None of that was true, either, but that didn’t stop thousands from believing in it.

Trump exploited these fictions, nodding to them deliberately with varying degrees of enthusiasm and plausible deniability. They were useful to him, stories in which he was a hero, and his political opponents were maximally morally repulsive. The conspiracies helped paper over the gap between the near-messianic esteem in which Trump’s followers hold him, and the shambolic, incompetent, and often cruelly sadistic character of his actual administration. And the content of the stories – dealing as they did in secrecy, power, helpless innocents and forbidden sex – made them potent tools, igniting the fiercest passions and darkest imaginations of his fans.

To a man with a bottomless appetite for self-aggrandizement and no principles, the conspiracy theories’ emergence must have seemed like a great stroke of luck. Trump lies like he breathes, and the national media, his fellow politicians, and all manner of experts have lost both the ability and the will to correct the record. Over the past 10 years, through the force of his personality and with mounting attacks on universities, journalists, and other outlets for knowledge building, fact-finding, and expertise, he has helped to accelerate a total epistemic collapse in national politics. Policy and public opinion alike are now unmoored from factual reality. What is true is no longer what matters.

The story of Epstein, the dead financier and prolific sexual abuser of young women and girls who killed himself in a jail cell in 2019, was in retrospect always bound to become a central character in these vast fantasies. Part of the reason is because of the true horror of Epstein’s crimes, and the uncanny ways some of the facts of his story – as demonstrated in court transcripts, unredacted documents, testimony from his victims, and the dogged, years-long investigations of the Miami Herald’s Julie K Brown – mirror some of the darkest details of QAnon’s fever dreams. A billionaire investor with ties to a shocking number of prominent people across the political spectrum – prominently including Trump himself – Epstein carried out his abuse of dozens of teenage girls over the course of years, allegedly trafficking them for abuse on his private island and aboard his private plane, and, according to some of the girls, now women, who have testified about their experiences with him, pawning them off for abuse by his rich friends. He was a man who lived in tremendous luxury, who mingled with the rich and famous, and who treated human beings – girls – as objects to be consumed, with a kind of casual indifference to their will or wellbeing. He was evil – and, to those on the right who seem to understand both conspicuous consumption and the sexual abuse of women as markers of status, he was also darkly aspirational. In some of the breathless coverage of Epstein, particularly as it emerged on the podcasts and web forums of the conspiracist right, you could detect in the fascination with Epstein not only moral revulsion but an acute envy.

It’s unclear why Trump is now trying to wrap up a conspiracy theory that has paid such dividends. Perhaps, as some are suggesting, Trump worries that sustained attention on Epstein’s case will draw more attention to his own abuse of women, though such revelations about Trump have been many, and have not hurt him before. Perhaps he just thinks that he cannot deliver, from his perch atop the federal bureaucracy that is so implicated in crimes and cover-ups in the imaginations of his supporters, the kind of earth-shattering revelations that the conspiracy theory’s narrative structures demand. Either way, Trump has turned abruptly and dramatically against the Epstein theory. He’s trying to reassert control over reality, trying to dictate which fantasies his movement adopts, and which they leave behind. It’s not working. The post-truth conspiracist world he helped to usher in is too unwieldy to be redirected at will.

There’s a grim irony in the fact that it is a case of sexual violence that has underscored the dangers of epistemic collapse for Trump himself, because sexual violence represents an arena where a post-truth reality long predates him. No one knows better than sexual violence victims, who are routinely disbelieved, dismissed, or punished for telling the truth, what it means for the facts of your own life not to matter as much as the passions and prior commitments of your audience.

What people tend to forget about Epstein’s life – clouded as it has been by all the speculation about his death – is that much of what he was doing to those women and girls was out in the open. Epstein had already been convicted and served prison time on charges pertaining to his sexual abuse; when he’d gotten out, he’d resumed his place among the rich and famous: his status was undiminished by the revelation of his violence. Maybe this is the real delusion at the heart of the conspiracy theories about Epstein and the other pedophile rings that populate the rightwing imagination: not that widespread sexual abuse happens, but that it is concealed, hidden, waiting to be unveiled by the righteous. For sexual abuse, at least, the real horror has always been this: that no one cares enough about the victims for the abusers to have to hide.

-

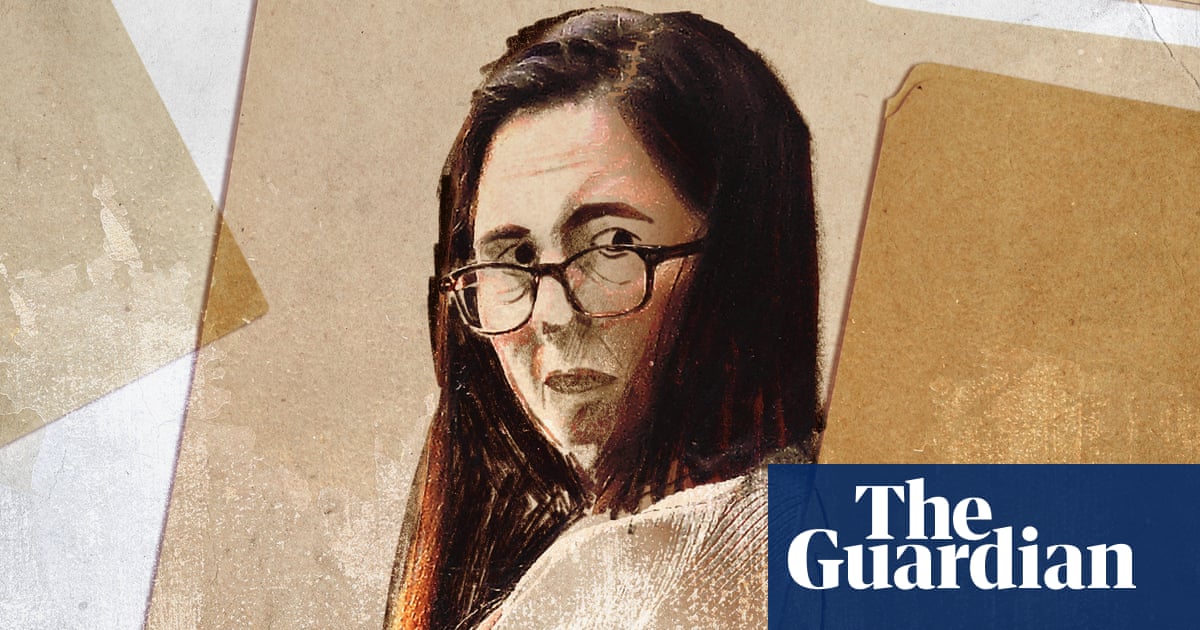

Moira Donegan is a Guardian US columnist

4 hours ago

4

4 hours ago

4