When Heinz Berggruen left Germany for America in 1936, he was not allowed more than 10 marks in his pocket. As a young journalist in Berlin, Berggruen had been forced to publish under the pseudonym “h.b.” in order to hide his Jewish heritage and evade the Nazi party’s antisemitism.

In the decades that would follow, he became an art dealer, regularly rubbing shoulders with the most important artists of the 20th century, and amassing one of the most impressive private collections of modern art ever to exist. On the day he left Berlin for Berkeley, however, such a future would have seemed impossible.

A year after Berggruen departed Germany, the Nazi party escalated its assault on culture by staging the infamous exhibition titled Entartete Kunst (“degenerate art”). Based on the belief that modern art represented a cultural decay and assault on German values, the regime confiscated more than 16,000 artworks and presented a number of them in an exhibition intended for public ridicule.

This invisible history is embedded in the artworks in the National Gallery of Australia’s new exhibition, Cézanne to Giacometti: Highlights from Museum Berggruen/Neue Nationalgalerie, which is mostly drawn from Berggruen’s collection and showcases many of the artists that the Nazis repudiated.

The first artwork that Berggruen ever purchased was a watercolour drawing by Paul Klee. The work, which he bought for US$100 in 1940 from another émigré in Chicago, immediately held personal significance. Berggruen described the artwork as his “talisman” and likely saw his own history reflected in the biography of Klee – a Swiss German artist, who had taught at the Bauhaus before being designated as “degenerate” and leaving Germany in 1933, the same year Adolf Hitler became chancellor. Berggruen would carry Klee’s watercolour drawing everywhere, even taking it with him when he was called up to serve in the US military.

“[The drawing] was probably a reminder of a world and home he had to leave behind, and a Germany that didn’t exist any more,” explains Natalie Zimmer, curator at Museum Berggruen, which is part of Berlin’s Neue Nationalgalerie. “Works by Klee really represented a cultural cosmos he was longing for … a reminder of everything that was good for Heinz, and very much the opposite to the Nazi regime.”

Artistic style can sometimes seem like an inward-facing conceit. Its importance is lauded by a subset of the art world – and yet, the greater distance one has from the context of its creation, the more ambivalent we as viewers can become to it. Similarly, the work of assembling a private art collection can be of critical importance to some – historians, institutions, the collector’s immediate family – and be of little to no interest to most gallery visitors.

But the Berggruen collection bucks both trends. Here, the modernist style is not just some idle indulgence, but a critical artistic counterpoint to the sanctioned aesthetics of the Nazis. Collecting such repudiated art was an act of resistance. Klee’s abstracted watercolour drawings, Alberto Giacometti’s elongated sculptures, Pablo Picasso’s dissonant Cubism: all despised by the Nazis and all now present at the NGA.

The story that the NGA is telling is primarily focused on the spread of modernist art styles across Europe and its eventual arrival in Australia. Here, the spread begins with the work of Paul Cézanne – a key precursor to the avant-garde movements of the 20th century, whom Picasso purportedly referred to as “the father of us all” – before moving on to trace his immediate impact on the artistic styles of Cubism and Fauvism, and its persisting influence on the generations of artists that followed.

after newsletter promotion

This influence is present even when it is not immediately apparent. “Giacometti is well known for his incredibly tall skinny sculpted works – but what on earth does that have to do with Cézanne?” asks David Greenhalgh, curator at the NGA. “Well, a lot. Giacometti had a painterly way of sculpting. He built his works up particle by particle – like the constructive brushstrokes of Cézanne.”

The basic lines of this narrative follow the conventional history of western art. Yet within the exhibition, this genealogy is extended out to encompass pockets of less-aired histories. Of particular note are the works by Dora Maar, whose Portrait of Pablo Picasso (1938) resists the well-rehearsed and reductive portrayals of her as merely Picasso’s muse by dramatically inverting the positions of artist and model. In the painting, Picasso is abstracted and unnerving, staring directly back with orange-yellow eyes and blank, black irises. Maar’s collection of black and white street photography further redefines her as an observer of life, rather than just the object of observation.

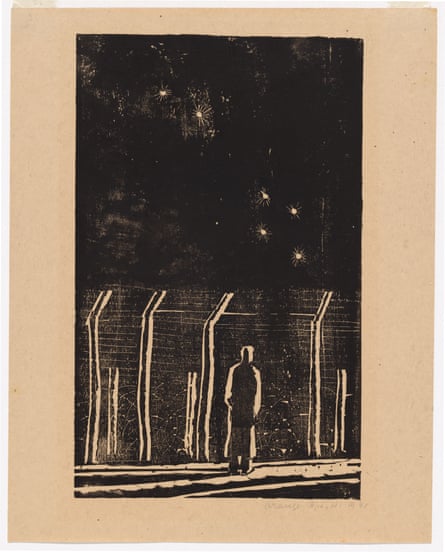

Ludwig Hirschfeld-Mack’s artworks are particularly arresting. The artist studied at the Bauhaus before being forced to flee Germany for England in 1936 due to his Jewish heritage. He was subsequently classified as an illegal alien and deported to Australia, where he was interned in camps in Hay, Orange and Tatura. The works that he made during this period import the lessons of the European avant-garde into country Australia to dramatic effect, aching with feeling and visually diarising the conditions of exile, as we witness in his woodblock print, Desolation: Internment Camp, Orange, NSW (1941).

In 2000, Berggruen sold his collection to the German state, seven years before his death at the age of 93. “It was a huge act of reconciliation by someone who was driven out of the city some 60 years before and still chose to give his works to Berlin, rather than Geneva or London,” reflects Gabriel Montua, director of the Museum Berggruen.

With this gesture, Berggruen helped to fill the historical gaps created by the Nazis’ violent confiscations – and left behind a collection that testifies to the power of art in moments of true peril.

-

Cézanne to Giacometti: Highlights from Museum Berggruen/Neue Nationalgalerie is on at the National Gallery of Australia until 21 September 2025.

1 day ago

10

1 day ago

10