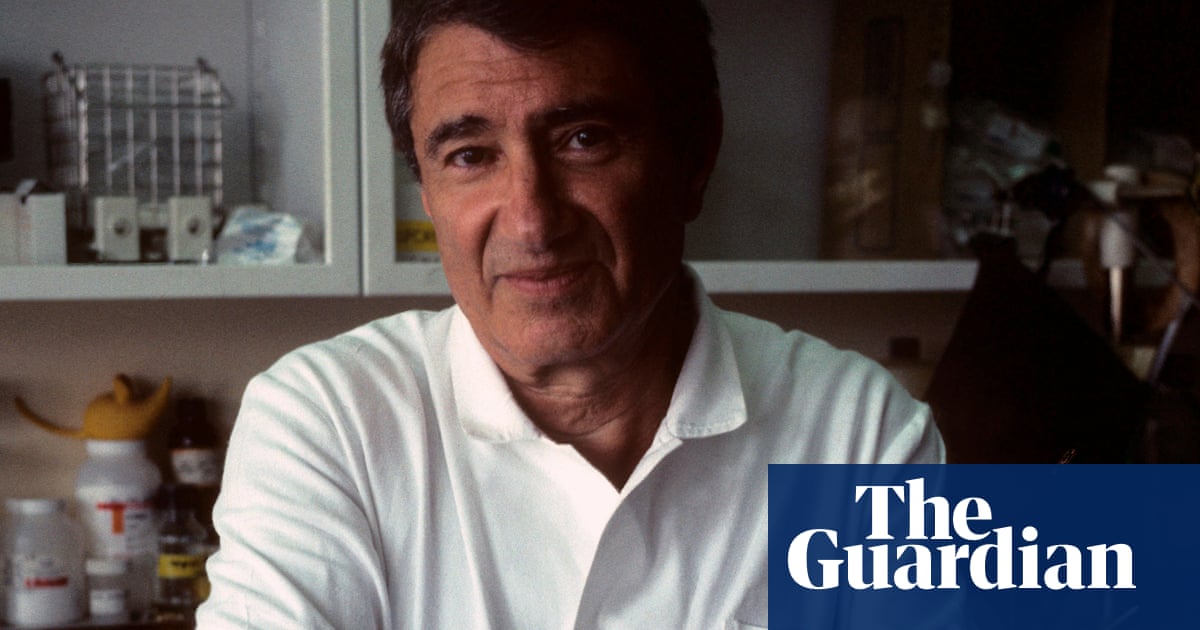

Of Timothy Leary, we know plenty. How, in the early 1960s, he gave LSD to his psychology students at Harvard, to the inmates of a maximum-security jail to see whether it would stop them reoffending, to artists such as Charlie Mingus and Allen Ginsberg to map how it expanded their creativity.

The Beatles’ song Tomorrow Never Knows was based on his writings. Mick Jagger flew to Altamont in a helicopter with him. He had perma-smile good looks, evangelical patter and likened himself to Socrates and Galileo. He even had a Pied Piper invitation: “Turn on, tune in, drop out”. No wonder Richard Nixon believed he was “the most dangerous man in America”.

What of Rosemary Woodruff? She was the fourth of his five wives, helping take care of his children in the long wake of their mother’s suicide. She buffed the branding of the self-styled “wisest man of the 20th century”. She fitted him with a hearing aid and sewed his clothing. She helped write speeches and the books that made him a must-read for any would-be prankster or beatnik. In 1970, she aided his escape from prison after he had been landed with a 30-year sentence for possessing drugs. She herself was forced underground for two decades. So much has been written about Leary, observes Susannah Cahalan: why so little about Woodruff?

Her life had been eventful long before she met the US’s most notorious trip adviser. She was born in 1935 in St Louis, Missouri to a father – Victor the Magician – who performed card tricks at local taverns, and a mother who was an amateur cryptologist. Early on, Woodruff wanted out. She needed, she said, “things to be grander than they were in my little neighbourhood, in my little home”. She decamped to New York, took amphetamines to ensure she was skinny enough to be hired as a stewardess for the Israeli airline El Al, and landed an uncredited role in a naval comedy called Operation Petticoat.

Woodruff was looking for otherness. She read Antonin Artaud and science fiction, explored theosophy, smoked cannabis and hung out at jazz clubs. She married a Dutch accordionist who yelled at and cheated on her; then a tenor saxophonist who, when he wasn’t shooting up, beat her and cheated, too. “I subscribed to ‘the genius and the goddess paradigm’,” she later reflected. “I wanted genius men.” She met Leary at a gallery and was taken by his talk of “audio-olfactory-visual alternations of consciousness”. They shared a ride to a psychedelic commune he’d established in upstate New York. What did she hope to find there, he asked. “Sensual enjoyment and mental excitement.” “What else?” “To love. You, I suppose.”

The following years are the stuff of legend. Leary titillated and horrified the US in equal measure, telling Playboy readers that women would have hundreds of orgasms during sex on LSD, and claiming that the drug would “blacken” white people so that they could pursue “a pagan life of natural fleshly pleasure”. When he ran for the governorship of California against an actor called Ronald Reagan, Woodruff devised the campaign slogan: “Come together, join the party”. Lauded for her cheekbones and elegance, she fed the press zingy one-liners, and was, says Cahalan, “a natural high priestess”.

Does this add up to the greatness that Cahalan believes Woodruff sublimated during her life with Leary? Cahalan describes him as a “so-called psychedelic guru” and “a sweet-talking snake charmer”. Does that make her heroine a gull? Cahalan astutely observes that, for much of the 1960s, “women were confidantes, calming tethers for the men to embark on frightening journeys into the psychic unknown”. In practice this meant, even when they were on the run, Woodruff ensured Leary never lacked for smoked oysters and fine wines.

Like the children of many LSD proselytisers, Leary’s son, Jack, got high at a young age. Home life was chaotic. He was so hungry and tired by the time he got to school that he could barely read the blackboard. Meanwhile, Leary’s daughter, Susan, taunted Woodruff for being “frigid and barren”, and played Donovan’s Season of the Witch at maximum volume for hours on end. Diagnosed with schizophrenia, she later killed herself in jail while awaiting trial on charges of shooting her sleeping boyfriend in the head. This is what Yippies co-founder Abbie Hoffman meant when he told Leary: “Your peace-and-love bullshit is leading youth down the garden path of fascism … ripe for annihilation.”

Biographies of lesser-known figures often end up high on their own supply. Their subjects are reappraised as radical, transformative, historical missing links. Cahalan is pleasingly sharp and satiric. She characterises some of Leary’s extended circle as “people who belittled their maids, fed their tiny dogs with silverware, and complained of the cost of shipping priceless art overseas”. Was Leary a visionary who foresaw today’s boom in microdosing? “Psychedelics have become too big not to fail,” Cahalan writes. “The twin issues that helped curtail the study of these substances in the 1960s are back: evangelism and hubris.”

Woodruff and Leary divorced in 1976, but her later life was far from boring. Travelling on a “World Passport”, a document created by peace activists, she zigzagged through Afghanistan where she used a burqa to hide contraband; travelled to Catania where she met a count and “made love in a secret grotto by a waterfall, drank grape brandy, and helped raise chickens”; to Colombia where she had encounters with venomous spiders and drug cartels. For many years she lay low in the US, lacking social security or health insurance, “an exile in her native land”. Only in 1994 was she able to emerge from hiding. While she never did publish the memoir she’d been working on for many years, The Acid Queen is a fond, imaginatively researched tribute to her free, forever-seeking spirit.

1 day ago

7

1 day ago

7