André de Ridder is either brave or stupid. He has accepted the role as the music director of English National Opera – its chief conductor and keeper of its musical flame. He will take up the role formally in 2027. The post has been empty for several anguished years, sparked by Arts Council England’s 2022 announcement that the company would lose all its funding unless it moved out of London. Amid a fightback that, to cut a long story short, resulted in the company retaining a foothold in the London Coliseum, but partially moving to Manchester, De Ridder’s predecessor, Martyn Brabbins, abruptly quit in 2023, saying that the company was heading into “managed decline”. Brabbins’s predecessor, Mark Wigglesworth, had also resigned suddenly in 2016, saying ENO was evolving into “something I do not recognise”. It was beginning to sound like an opera plot. Bluebeard’s Castle, maybe. A murdered conductor behind every door in the mansion.

And yet: De Ridder’s enthusiasm is irrepressible. For some, it would be daunting to come into a company whose world-class orchestra and chorus have had their full-time contracts slashed to seven months of the year; from which the chief executive has just resigned; where morale (insiders tell me) is rock bottom. But the Berlin-raised 54-year-old sees only the opportunities. From his perspective, the shake-ups are in the past.

“I like this construction of London and Manchester,” he tells me, at the Coliseum. “And I like the spirit of pioneering, of becoming an opera company in a city that previously hasn’t had a resident opera company.” We are speaking before rehearsals of the show he’s conducting, Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny, Bertolt Brecht and Kurt Weill’s rarely performed morality tale about rapacious capitalism.

He feels a strong connection to Manchester: he studied at the Royal Northern College of Music for two years, and was later assistant to Mark Elder at the Hallé. The new setup presents a “great chance for an opera company and a great chance for opera at large” to develop a new audience in Greater Manchester, “and maybe one that has no preconceived ideas of what opera is”. Opera North regularly visits Salford (and, a fact seemingly overlooked by the Arts Council, was set up in the 1970s to be ENO in the north). But the more the merrier, he thinks. The scene “should just get richer and richer”.

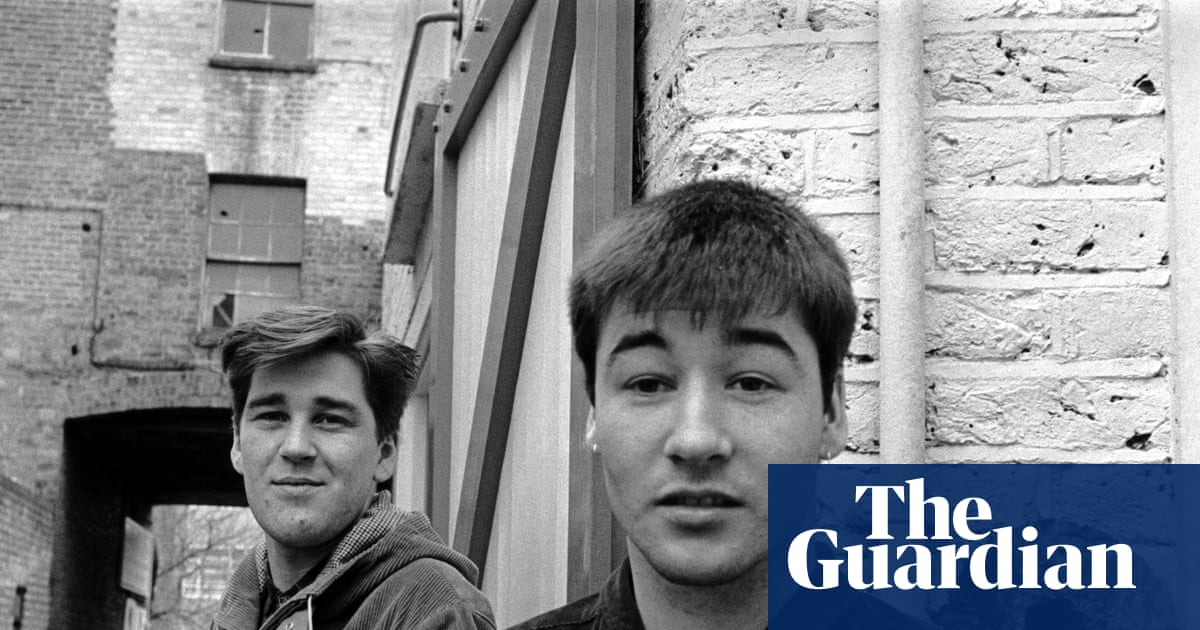

He knows his predecessors well – including Edward Gardner, who did the job brilliantly from 2007 to 2015. The two actually studied together in London, and took classes from Brabbins, who was a guest teacher on their conducting course. So was Elder, who was music director of ENO in the 1980s and 1990s. De Ridder says of Gardner and Brabbins: “I love them both dearly, and admire them greatly as conductors, but for the moment, I’ve chosen to not speak to them because I wanted a clean beginning, no baggage. I just want to make up my own mind about how things are standing.”

He talks about the Manchester plans ENO recently announced – among them the UK premiere of Angel’s Bone, by Chinese-American composer Du Yun, which will be staged at Aviva Studios in May. With works like this, its subject modern slavery and human trafficking, there is a chance to expand the boundaries of the form, he says. “Du Yun is a modern example of the kind of thing Kurt Weill did 100 years ago,” he says, “incorporating punk and cabaret in classical contemporary music in a new way”. He adds: “The opera world can be quite an inward-looking and closed-up sort of place, a famous museum. Manchester makes us rethink what opera means, what it can be.”

The orchestra for Angel’s Bone will be the Manchester-based BBC Philharmonic. But surely ENO is by definition a company: it consists of its chorus and its orchestra, its backstage staff, its people. If you produce work in Manchester without the company, is it really ENO at all? On the other hand, bringing London-made ENO productions to Manchester is not only expensive but a little imperialistic. Is there not a fundamental problem with the dual-centre theory? “It’s not just a one-way street,” says De Ridder. Work created in Manchester may come to London, while “we are trying to find ways to present work with our core ensembles in Manchester”. (One example is a semi-staged performance of ENO’s Così Fan Tutte at Bridgewater Hall later this month.)

De Ridder has, above all, history with ENO. As a student in 1996, he watched shows such as Bernd Alois Zimmermann’s vast opera Die Soldaten at the Coliseum. (He would love to see ENO in the future similarly performing landmark near-contemporary works that have never been seen in the UK before – Messiaen’s Saint François d’Assise, say, or Kaija Saariaho’s Adriana Mater.) Most importantly, 20 years ago, when he was in his early 30s, he conducted the premiere of Gerald Barry’s remarkable opera The Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant, based on Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s 1972 film.

“ENO schooled me, ENO formed me as an artist on the operatic stage,” he says. “It was a lucky time and place. Richard Jones was directing, one of the greats, and Barbara Hannigan [Canadian soprano and now conductor] was making her operatic debut in the UK.” There were “seven or eight intense weeks in the rehearsal room”, he remembers. “The togetherness, the vision, the knowing that we’re doing something quite special, how everybody pulled together – I was spoiled for life by this experience. And I tell you, it’s not the same everywhere. I expected it to be like this everywhere. It wasn’t, and it’s not. And so when this job came up and we started talking, I thought, ‘I have to put my hat in the ring.’”

It’s not the same now, though, is it? The musicians and choristers are depleted. He’s getting three, not eight, rehearsal weeks for Mahagonny, and only three performances. But he still believes. “The core of the orchestra is there. The chorus is there. And the spirit of ‘Let’s do it’ is there.” A couple of days after we speak, he messages me. “It wasn’t, nor would it have been, my choice to shorten contracts of the core performing groups of ENO,” he clarifies. “I’ve come in after this was decided and resolved, and I can only imagine how tough that must have been. But now my brief is to hold up ENO’s excellence and goals for everyone.”

He talks passionately about Weill – whose numbers, such as Alabama Song, long ago took on a life of their own thanks to, among others, the Doors and David Bowie. Mahagonny comes out of the heady musical melting pot of 1920s Berlin – the city, too, of Schoenberg and Hindemith. “Kurt Weill is often seen as the guy who did the jazzy thing and the sassy thing. But in this piece, you can see he grew up through the school of Schoenberg and using old forms – canons, fugues, chorales, and some of the tonal-based, modal framework that Hindemith ended up with. You see all these influences, but also ragtime, tango, American blues music. There are moments of pure Gershwin.” His own father used to conduct the opera, along with other Brecht and Weill masterpieces, in West Berlin in the 1980s. He’s using his dad’s score.

De Ridder is currently music director of the opera in the German city of Freiburg. Why exchange comfortable funding and long rehearsal periods for ENO’s shaky situation in a cash-strapped country that may well get a far-right government after the next election? He laughs. “I think we’re far closer to getting a far-right government in Germany than you are,” he says. “It’s not the reason I’m leaving Germany, but you just said the word ‘comfortable’, and that’s the operative word. It is comfortable, yes, maybe a little bit too comfortable.”

When we speak, he has just been working at 3 Mills Studios in east London. “There were three ENO productions being rehearsed there at the same time, Così Fan Tutte, Mahagonny and a brush-up of [Gilbert and Sullivan’s] HMS Pinafore – and the buzz in the building was incredible. It felt like life and death.”

He adds: “I love working in Germany. I love that in every city there’s an opera house. But people are comfortable.” He looks around the Coliseum and says: “That make-or-break feeling I had when I first came here? I love it.”

3 hours ago

3

3 hours ago

3