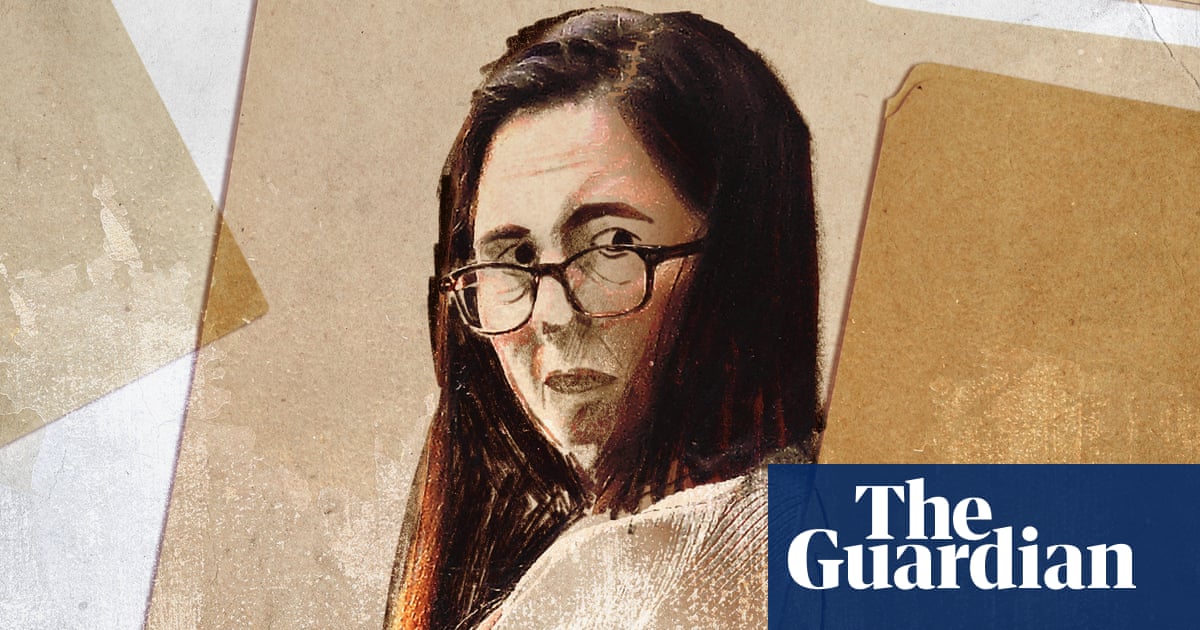

In late October 2022, as protests over 22-year-old Mahsa Amini’s death in police custody swept across Iran, Rezgar Beigzadeh Babamiri, a father of three, was racing through alleyways in the city of Bukan, in western Iran, carrying medical supplies to secret clinics where doctors treated injured demonstrators in defiance of the state.

Many of the wounded were too afraid to seek hospital care after reports of secret police patrolling wards, interrogating patients and detaining injured protesters. By helping, Babamiri, a 47-year-old fruit and vegetable farmer, did not see himself as a revolutionary but simply as someone doing what was right, says his daughter, Zhino.

“There was intense firing from the forces and many protesters were injured. Everyone was helping each other and he volunteered,” she says.

“I told him not to talk about it openly on the phone, but he said it wasn’t dangerous to help injured people. He just couldn’t watch young people bleed in the streets.”

Babamiri was arrested in April 2023 and questioned by the ministry of intelligence in Bukan. Zhino, 24, says the family initially believed it was a brief interrogation. “I was told [by relatives] not to worry and that he’d be home soon,” she says.

Instead, he disappeared into solitary confinement and was initially denied access to a lawyer or contact with his family, the Kurdish Human Rights Network says.

Last week, the family heard from a lawyer that Babamiri had been sentenced to death, along with four other Kurdish men, after being charged with “armed insurrection”, “leading and forming an armed group” and “espionage for Israel”.

Zhino, who lives in exile in Norway, says the family have been horrified by the verdict. “When I heard about the death sentence, I was numb. When I called my grandmother and aunt, they were crying loudly. I have never heard them cry like that.”

Since his arrest, Zhino says several people have come forward with stories of how her father helped save their lives.

“These charges have been fabricated. My dad is a simple farmer who loves the people of his community and his family. He is a man who loves poems, likes watching news and enjoys working out,” she says.

In July 2024, Iranian state media aired a video showing Babamiri confessing, alongside other men charged in the same case. Human rights groups say his conviction was based on a forced confession.

In a letter later smuggled out of prison to the family, Babamiri described enduring more than four months of torture, including waterboarding, electric shocks, mock executions, and beatings that left him partially deaf.

“When I first read the letter, I skipped the parts about torture. I couldn’t bear to see what they did to him,” says Zhino.

after newsletter promotion

Amnesty International says Babamiri’s arrest in 2023 came during a wave of detentions and executions of students and activists after the 2022 protests, part of the Iranian regime’s campaign to instil fear and maintain control.

Amnesty has also repeatedly documented the regime’s arbitrary arrest and detention of Kurds – an ethnic minority in Iran – based on perceived affiliations with opposition groups, often without credible evidence.

“My dad and the others are paying the price for simply being born Kurdish,” says Zhino. “They told him no one would care if he died and that he’d end up in a mass grave.”

Zhino says members of her family still living in Iran are fearful, and that she was advised by well-wishers to stay quiet after his arrest. “I regret that. The silence didn’t protect him and it almost broke me,” she says.

She has become an outspoken campaigner, co-founding Daughters of Justice, a group of Iranians fighting to save their imprisoned fathers.

In her most recent phone call with her father, he could not hear her. “He kept saying, ‘Zhino, are you there?’. I could hear him, but he couldn’t hear me. I was crying. That moment haunts me.”

She now waits every day for news of his fate. “I am scared to check my phone,” she says. “I’m terrified I’ll wake up to read my father’s name [on the death list].”

5 hours ago

5

5 hours ago

5