Located about 500km off the southern coast of Baja California lies a group of ancient volcanic islands known as the Revillagigedo Archipelago. Home to large pelagic species including whale sharks and scalloped hammerheads, the rugged volcanic peaks were also once the site of an unlikely friendship.

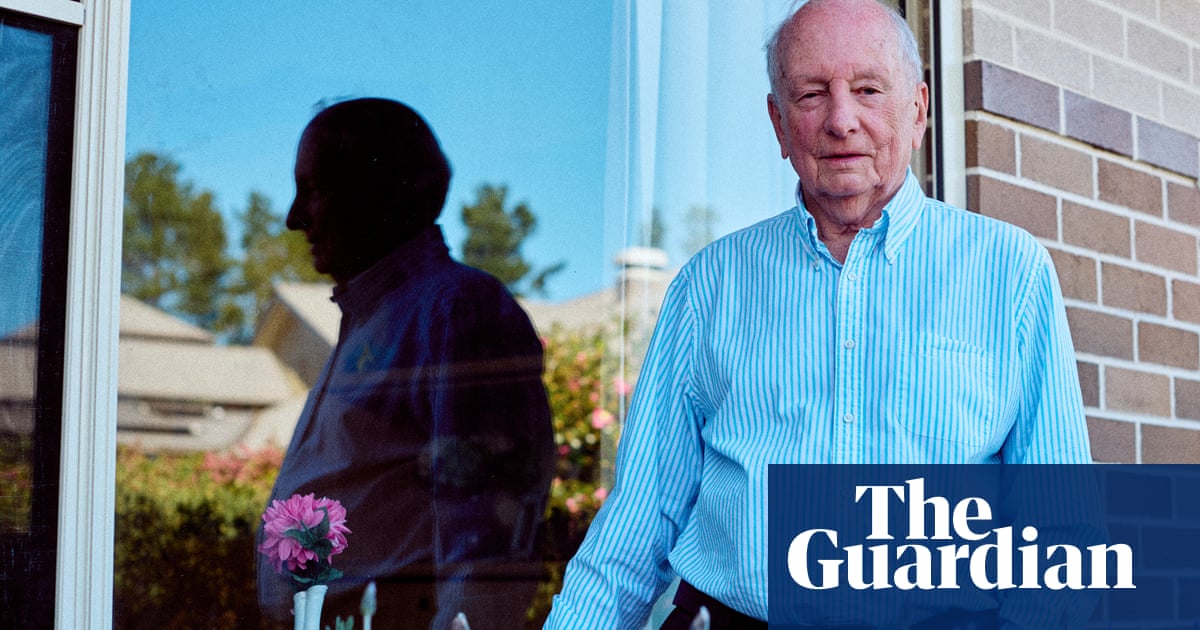

It began in December 1988 when Terry Kennedy, a now 83-year-old American sailor with a storied past, met a six-meter-wide giant Pacific manta ray off San Benedicto island’s rugged shore. He would go on to name him Willy. “When I saw him beside the boat, as massive as he was, I just had to get in the water just to see him,” says Kennedy. “I threw a tank on and jumped over, but I didn’t see him anywhere. He couldn’t have vanished that quick. And then I looked straight down and he was coming up underneath me. He was about four feet away and rising so I had no way to get off his back.”

Together, on that day and over the next decades, the two rode through the water, with Willy taking Kennedy around the underwater volcanic peaks and as far as two miles, only to always return Kennedy to his boat. Now, 37-years on, their unlikely friendship will be explored in a new documentary called The Last Dive, released on Sunday ahead a series of limited screenings in the US and New Zealand.

In it, Kennedy embarks on a final journey to the island in the hope of reuniting with the ray. With its focus on a relationship between man and beast, it will undoubtedly draw parallels to Netflix’s 2020 documentary The Octopus Teacher, which told the moving story of how Craig Foster came to know an octopus.

Film-maker Cody Sheehy hopes that showing the film will “inspire a whole new generation” to fall in love with the ocean. “For me, it’s personal,” he says. “I live with my wife and two-year-old son on a sailboat. Every night, I drift off to sleep with the sound of the ocean slapping our hull. Over the last 20-plus years, I have watched life in the ocean disappear.”

When Kennedy and Willy met, very few divers understood the harmful impacts that could come with touching a wild animal – a practice that has been banned globally across federally protected marine areas and dive sites. Harmful impacts from physical touch include significant stress and behavioral changes across mantas.

Yet, at the time, Willy, with his four distinctive black dots in the shape of a diamond on his right shoulder, and Kennedy, formed an inexplicable bond of trust and respect that Kennedy documented with his video camera. Coming up to Kennedy’s boat and slapping his fin against the hull, Willy would wait for Kennedy to climb on his back before taking off for a ride around the island.

On multiple occasions, Willy helped Kennedy locate abandoned nets. “He drove me crazy one day trying to get my attention,” says Kennedy. “Finally, I moved off from the other two divers, got on his back, and he took me off and we run on down. Next thing I knew, I see the bottom coming up, and there’s this giant net, far bigger than anything I’ve ever seen before.

“I realized early on, he took me to the full perimeter of the net. He was purposely showing me what was there, how big it was,” Kennedy says. He went on to contact the Mexican navy and in two days, Kennedy, alongside a large gunship and navy divers, pulled up 17,050 meters of net.

Another time, Willy positioned himself between Kennedy and a great hammerhead shark during one of Kennedy’s dives.

“He turned around and came up in front of me and was kind of dogging me, back and forth. I thought he wanted to go for a ride but I’d break to the right, he’d break to the right. I couldn’t understand what was going on with him. Finally I did a jig and jog and I looked around and there was an 18ft great hammer,” Kennedy says in The Last Dive.

“I thought to myself, ‘Whoa. Willy protected me,’” he adds.

With the largest brain-to-body-mass ratio compared with other fish, mantas are highly intelligent creatures. As curious filter feeders, mantas can recognize themselves in a mirror, demonstrating a rare sign of self-awareness comparable only to a few animals including primates, elephants and dolphins.

Yet these docile creatures are listed as threatened under the US Endangered Species Act, with thousands being targeted and killed each year for the trade in their delicate feeding gills or merely caught as bycatch across legal and illegal fisheries.

Kennedy’s friendship with Willy changed not only his approach to wildlife underwater but also pushed Kennedy, then a big game fish hunter, into his unlikely role of conservationist.

In 1994, Kennedy captured on camera the slaughter of multiple mantas on Valentine’s Day at San Benedicto island – including ones that swam with Kennedy the day before. After the incident, which prompted international outcry, Kennedy became a vocal proponent of federal fishing regulations, successfully pushing the Mexican government to declare Revillagigedo Archipelago a nationally protected marine reserve.

“What happened out in San Benedicto, I just pretty much said, ‘That’s enough for me.’ I’d rather shoot them with a camera and from that day forward, I got along with the big fish that would actually come close to me. I don’t know what it is when they no longer felt any fear of me,” he says.

Kennedy’s relationship with the ocean has evolved over the years. The self-confessed “troubled kid” growing up in California started diving at 12 years old – his first dive being a 200ft dive on his own. He served in the US navy in Vietnam and later was a Hells Angel biker, a bar owner and a wild sailor living onboard his boat – once named Erotica – on the Pacific.

But as his relationship with the rays deepened, he found he was his truest self under the water. For Kennedy, who has done more than 14,000 dives: “My world starts when I go below the surface.” Since meeting Willy, that world has become one he and his ocean collaborators are dedicated to preserving.

Amid a global decline in mantas and rise in poorly regulated dive boats leaving them frequently injured and their fragile ecosystems disturbed, the need to protect mantas is more urgent than ever. “There are so many dive boats out there that if we don’t dive responsibly with them, it might affect how they [the rays] feed underwater,” says Sheehy.

Sheehy, who dived with Kennedy in the archipelago, also points to boat traffic, saying: “The mantas want to come up to the top, they’re hard to see and they’re getting hit by boats. And I think that is the real pressure that tourism is bringing that we need to talk about.”

The urgency for increased marine regulations also comes as Donald Trump’s administration sets a dangerous example to other countries to disregard environmental protections. The US’s latest environmental rollbacks from commercial fishing proclamations to delisting certain animals as endangered species threaten the overall wellbeing of marine wildlife.

Though rare, the bond between Kennedy and Willy offers a profound glimpse at a shared bond that is possible when such creatures are given the chance to live and thrive.

“Willy showed me what needed to be done, and I’ve just done it,” Kennedy says.

5 hours ago

3

5 hours ago

3