Vincent van Gogh was born in 1853, in the middle of the comparatively peaceful 19th century. If he hadn’t shot himself in a cornfield at the age of 37, and had made it to his 60s, he could have witnessed all that end in the 1914-18 war. If he’d lived to 80, he would have read in his newspaper, at an Arles cafe table, of the election of Adolf Hitler as German chancellor, and in 1945, at 92, watched newsreel footage of the emaciated survivors of Belsen.

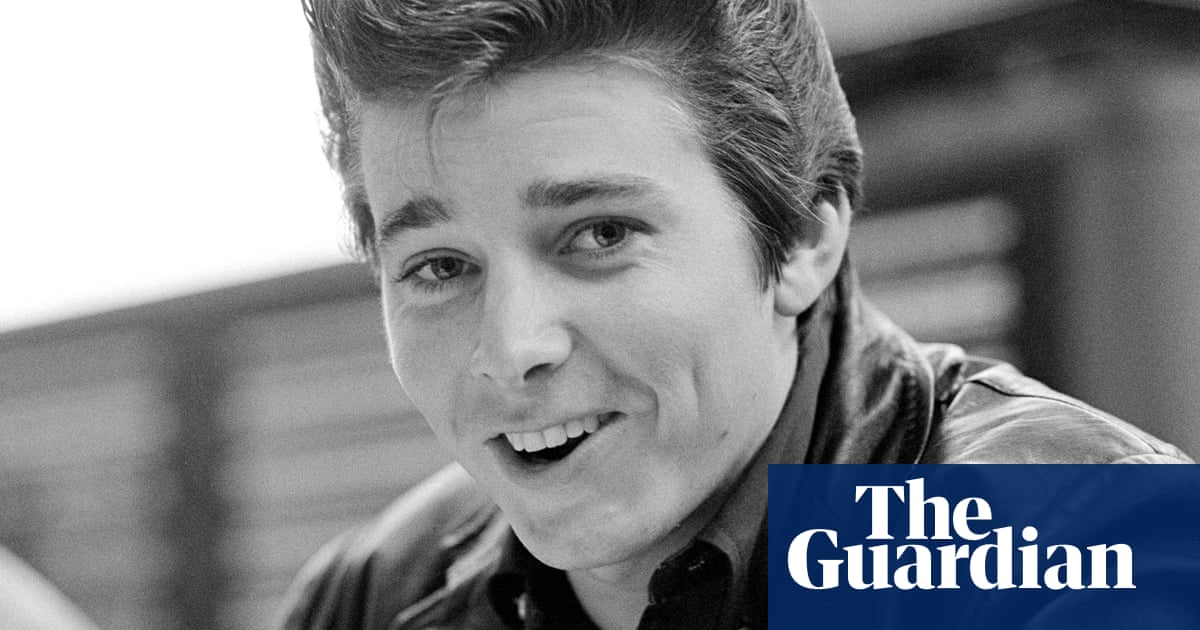

Odd thoughts, but they are stoked by the Royal Academy’s strange and startling exhibition. This is an intimate encounter between the great living German history painter, to mark his 80th year, and his hero Van Gogh. It juxtaposes his responses to the latter, from teenage drawings to recent gold-spattered wheatfield scenes, with the Dutch artist’s works. The peculiar result is to make you see how the dreamer of sunflowers and starry nights might have painted the horrors of modern history, if he’d lived to see them.

Kiefer was born in 1945, as the facts of the Holocaust started to emerge in Germany’s ruins. His art has been a long war against forgetting, fought with paintings, actions and installations. This exhibition includes his 7.5m wide 2019 canvas The Last Load, a European landscape under a black sky, emptied out by history, a gnarled waste land of stumps and stubble, including straw stuck into the masses of earthy paint. You just know what it’s about. Every ploughed furrow receding across the dead space looks like the rail tracks to Auschwitz.

Nearby is a pair of abandoned shoes: Van Gogh’s, in his 1886 painting Shoes. But in this context these battered, lifeworn boots – two cenotaphs for vanished feet – look like the many shoes, suitcases, glasses and other objects left by the murdered. Another Van Gogh painting here, Piles of French Novels, takes on the same memorial quality: a pile of books, a heap of forgotten stories.

It is Van Gogh’s disturbing ability to step outside of himself and paint his shoes and books as if they were relics of a dead man that makes him appear, through Kiefer’s dark lens, a prophet of the Holocaust. It’s a convincing, if harrowing, image of him. At the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam earlier this year, a different version of this show refused to see anything macabre or morbid in Van Gogh’s art, and consequently made little sense. Here, Kiefer and Van Gogh blend together in a weird Romantic death dance – or, to use the title of a poem about the Holocaust by Paul Celan that has long obsessed Kiefer, a Death Fugue.

So a vast canvas by Kiefer sends giant black crows hurtling towards you over waving wheat in a colossal restaging of Van Gogh’s last, or nearly last, suicide note of a painting, Wheatfield With Crows. In case you miss the deathliness of these winged messengers, Kiefer calls it Nevermore. Or as Celan wrote: “we dig a grave in the sky there is plenty of room”.

There’s nothing subtle about Kiefer’s vision of Van Gogh. It’s as bold and sentimental as Don McLean’s Vincent. Fair enough. Van Gogh reaches out to us, our hearts go out to him. Kiefer portrays himself lying down, floored by weltschmerz, or world pain, in a field of giant sunflowers. They are black. He sees the gloom even in Van Gogh’s brightest theme, but amazingly, the curator finds a match for these blooms of death in Van Gogh’s 1887 painting Sunflowers Gone to Seed, a sad grey-brown study of dead, drying nature.

Even Van Gogh’s 1890 Poppy Field looks here like a prophetic poem to the Flanders fallen – a sea of blood-red flowers under the uneasily placid sky. The hint of tragedy is really there, for this is another ruminatory landscape from Van Gogh’s final months.

So the show spookily succeeds in making Van Gogh look like Kiefer. But Kiefer doesn’t come off so well when he tries to look like Van Gogh. The Dutch artist can be as bleak as he is here, yet he also paints ecstasy and (brief) hope in the Provence sunshine. Kiefer doesn’t have that joy in him – and when he tries to lighten up, he looks fake, splashing gold leaf over real corn stuck on to canvases enormous in scale but lacking intensity.

Still, that too is a truth. Despite the intimations of modern disaster that this exhibition brings out, Van Gogh painted before 1914, before Auschwitz. He painted a more innocent nature. The snow enveloping the fields, in a wonderful wintry scene he painted in 1890, may look like ash if you squint enough, but it’s still just snow. Kiefer can’t see nature with the same fresh joy because no one can any more. His metallic attempts at golden ecstasy reflect our time, our sorrow.

7 hours ago

5

7 hours ago

5