It was celebrated at the time as a major milestone for progressive education. In 2021, California became the first state to make ethnic studies a graduation requirement, mandating all high schools teach the subject by fall 2025.

The idea, championed by California’s governor, Gavin Newsom, was to bring modern concepts into the classroom. At its core, ethnic studies, an academic discipline born on California campuses during the civil rights movement, elevates the experiences of historically marginalized groups. Its materials push students to question their biases, reimagine power structures, and think critically about the enduring legacies of colonialism. In California high schools, courses would bring to the fore the experiences of Chicano, Black and Indigenous communities in the state by diving into issues such as gentrification, the impact of pesticides on farm worker communities and the legacies of Indian boarding schools. Many school districts enthusiastically jumped on board.

The idea to make ethnic studies part of the curriculum always had its detractors. But it gained significant support after the racial justice protests of 2020. Today, however, ideas that rose to the vanguard of American culture after that period’s uprising have fallen dramatically out of political favor, and ethnic studies is now the center of an acrimonious battle over what constitutes antisemitism – and whether students should be learning about international conflicts, namely the fraught histories of Israel and Palestine – in courses meant to lift up the diverse experiences of Californians. The controversy has resulted in lawsuits and threats to ban certain concepts and materials entirely.

In a dramatic heel turn, state legislators earlier this year proposed a bill that would have significantly restricted how the subject could be taught. While the effort faltered, Newsom has since withheld the funding needed for the new course requirement to go into effect by the fall deadline, potentially propelling the initiative toward anticlimactic collapse. In some cases, districts are reeling initiatives back of their own accord; last week San Francisco unified school district announced it would pause the development of its own ethnic studies curriculum following complaints from parents that the material was too progressive.

The saga underscores how deeply politics have infiltrated schools, even in a liberal state like California. It also has illuminated a gaping chasm in worldviews that is playing out nationally: what one side views as inclusivity the other views as leftwing indoctrination, and neither side appears willing to compromise. In the crosshairs are American public schools.

California is the birthplace of ethnic studies as a discipline.

In the late 1960s, as student protests roiled much of the world, students of color at San Francisco State University launched the longest student strike in US history to protest what they viewed as Eurocentrism in education. Among their demands was the establishment of ethnic studies departments that would give voice to marginalized groups.

The field’s interdisciplinary philosophies would come to be embraced by universities nationwide, and ethnic studies departments were established at a host of college campuses, including in more conservative states. After the racial reckoning of 2020 that came out of the murder of George Floyd, ideas previously reserved for the halls of universities and the pages of academic books – such as postcolonial theory and intersectionality – entered the public conscience.

While 24 states have incorporated some elements of ethnic studies into their K-12 curricula, California lawmakers stand alone in having mandated it as a graduation requirement. In some ways, the most diverse state in the nation, with a 60% non-white population, was a natural fit for the requirement. But in hindsight, it’s not clear whether lawmakers understood the radical nature of the concepts they legislated into public school curricula.

The policy’s rollout has been rife with disagreements from the beginning, stemming in large part from a spirit of flexibility that has made for murky guidelines.

The law required California high schools to have a course available by the fall of 2025 and stated that to graduate, members of the class of 2030 would need a one-semester ethnic studies course on their transcript. That course could take a number of forms, depending on the school’s structure, resources and priorities, explained Tricia Gallagher-Geurtsen, an ethnic studies lecturer at the University of San Diego. A school can write its own course based on the state’s model curriculum or use one that has been pre-approved by the University of California system. And while most ethnic studies classes are categorized as history or English courses, there is nothing to stop a school from designating a math course as its ethnic studies prerequisite. “It could be a statistics course that looks into measuring racial inequities,” Gallagher-Geurtsen said.

Ultimately, legislators left the development of curricula up to individual schools and teachers who weren’t necessarily trained in ethnic studies, which is a discipline with strict theoretical parameters. This lack of clarity has resulted in experimentation, disagreement and, in some cases, heated animosity, on the ground.

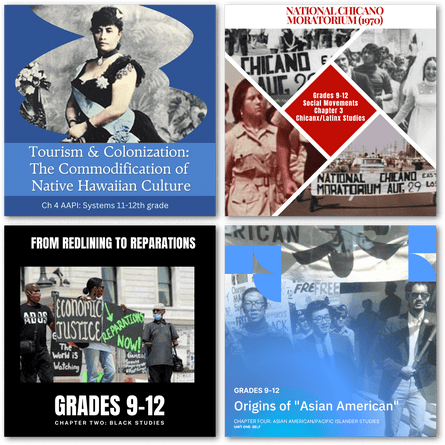

In 2019, before the subject was made mandatory, the state released its first draft of an ethnic studies model curriculum that teachers could voluntarily incorporate or adapt for local school board approval. The model text, which was created with input from an 18-member committee of hired academic experts from universities around California, focused on the four populations considered by ethnic studies experts to be the driving force of the discipline in the US: Black, Chicano and Latino, Asian American and Pacific Islander, and American Indian and Native American.

“This is how ethnic studies categorizes itself,” explained Gallagher-Geurtsen. “[It] centers racialized groups of color first.”

Different groups were upset about it for various reasons, but there was recurring protest over the model text’s representation of Israel as a colonial oppressor state: a characterization that academics in the field say is central to ethnic studies as a discipline. That drew protests from Jewish groups that criticized the material’s failure to address antisemitism. Rightwing advocacy organizations also accused the text of promoting a leftwing agenda grounded in critical race theory, objecting, for example, to its claim that the “war on drugs” as fundamentally racist.

The curriculum was ultimately rejected by the California board of education, and a new committee was brought in to draft more politically palatable guidelines that were “free of bias”.

When that happened, Ndindi Kitonga, an ethnic studies lecturer at California State University, Long Beach and founder of an alternative school in Los Angeles, grew concerned that the new panel lacked direction from experts trained in the academic discipline. She wanted to make sure that the guidelines sent to classrooms reflected topics that are fundamental to the academic field – such as resistance to oppression and solidarity across social movements – rather than the priorities of policymakers. On those points, the discipline cannot compromise, Kitonga and other ethnic studies scholars emphasized.

So Kitonga, along with fellow academics and activists in the field, decided to make material of their own for teachers to use. Independent of the state, they designed sample ethnic studies lesson plans for teachers to access for free online. The lessons are organized into units themed around the four groups of focus, and primarily focus on teaching hyper-local histories. Students are encouraged to learn about how phenomena such as gentrification have unfolded in their own neighborhoods, for instance, and to visit local archives.

But the materials also make connections between the experiences of marginalized groups in America and those of oppressed groups around the globe, including Palestinians.

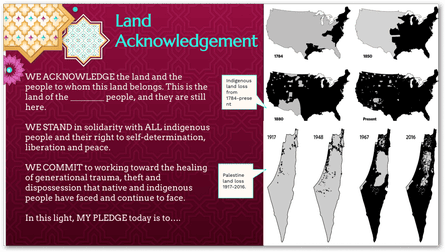

In a slide from a model lesson plan focused on contemporary Arab American identities and experiences, for instance, images showing the loss of land belonging to Indigenous groups in the US is pictured alongside images showing shrinking Palestinian territory in the century that followed the 1917 Balfour Declaration, through which Britain voiced support for the establishment of a Jewish state in the region. Students are invited to draw comparisons between the two histories.

Kitonga and her colleagues called the initiative the Liberated Ethnic Studies Model Curriculum Consortium – “liberated”, that is, from legislators’ interests.

The response from teachers in the two dozen districts that have adopted curricula designed by the consortium has been positive, said Gallagher-Geurtsen, who helped found the consortium. “It affirms who students are and recognizes their experiences in a deeper way than any curriculum ever has,” she said. “Teachers have said it’s the most rewarding teaching they’ve ever done in their lives.”

Research shows that teaching ethnic studies raises grades and test scores for students of all backgrounds across all subjects, increases graduation rates, and improves relations and understanding across races and ethnicities. And for Kitonga, the controversy distracts from those benefits.

“That’s never talked about in the news,” she said.

Instead, headlines have been drawn to accusations of antisemitism in ethnic studies classrooms.

Across the state, groups of concerned parents have sued school districts, alleging that teachers have exposed students to antisemitic material and ideas in ethnic studies lessons that characterize Israel’s actions towards Palestine as an example of colonial oppression and genocide. While these accusations predated the Hamas attacks of 7 October 2023 and Israel’s subsequent bombing campaigns in Gaza, the frequency and intensity of tensions have mounted since.

In LA, parents lost a suit claiming that teachers who identified as Zionist felt unwelcome in ethnic studies classrooms; in San Jose, an ongoing suit alleges that an ethnic studies teacher characterized Jews and Israelis as oppressors and “exploitative capitalists”, leading Jewish students to be be ostracized and harassed; and in Santa Ana, the school district settled with Jewish parents and community members who claimed to have been deliberately excluded from public discussions in which curricula were developed and approved – a violation of the state’s Brown Act, which demands open legislative meetings.

Rachel Lerman, vice-chair of the Louis D Brandeis Center for Human Rights Under Law, which filed claims on behalf of plaintiffs in the Santa Ana and Sequoia cases, claims that parents in Santa Ana were refused access to class materials after directly approaching schools and teachers, and that school board members considered holding meetings on Passover, a major Jewish holiday, so that Jewish community members could not attend.

Lerman said the deliberate exclusion of the Jewish community from civic discourse is both antisemitic and directly harms Jewish kids. “It leads to bullying of Jewish students, to the exclusion of Jewish students from school clubs,” she said, adding that she has spoken with many Jewish parents who have elected to take their children out of local public schools, citing antisemitism.

But advocates – as well as school districts and even courts – have pushed back, arguing that criticizing power structures, including foreign governments, drives ethnic studies and is not discriminatory. Last year, a Palo Alto school district refuted parents’ claims that its ethnic studies course was politically radical, while a judge threw out the case brought against LA ethnic studies educators on the grounds that “learning about Israel and Palestine” does not constitute “injury”.

Teachers have pushed back, too. In April, Chloe Gentile-Montgomery, a Bay Area ethnic studies teacher who was placed on leave for allegedly including antisemitic material in a slideshow concerning Israel and Palestine, sued her former school district. Gentile-Montgomery claims racial discrimination and failure on the part of her employer to protect her from harassment from students and parents. While other teachers in the district taught about Israel and Palestine without consequence, Gentile-Montgomery, who is Black, was “singled out” and targeted, according to the lawsuit.

Asserting that she has seen no convincing evidence of prejudice levied against ethnic studies educators, Gallagher-Geurtsen said that these incidents are examples of antisemitism being conflated with criticisms against a foreign government – with the latter being a perfectly acceptable exercise for high schoolers to undertake, she said.

“Curriculum that makes you feel uncomfortable does not violate your rights,” she said.

In some ways, the fight against ethnic studies is a story very specific to California. In others, it’s a microcosm of trends playing out on a national stage: polarization, censorship, and a cultural and political retreat from progressive ideas, especially in education.

Those divisions have only been exacerbated since the war in Gaza and Donald Trump’s return to office. Since the 7 October attacks, the US Department of Education has investigated at least 40 K-12 schools for discrimination and antisemitism. Under Trump, the assault on educational institutions has escalated dramatically with antisemitism investigations against dozens of universities and a dramatic campaign against the academic independence of schools such as Harvard and Columbia.

In California, a group of state lawmakers have tried to address what they describe as an unbridled course mandate that has given teachers too much leeway, paving the way for antisemitism to enter the classroom.

“School districts have proceeded with content that isn’t appropriate for all kids and [that is] antisemitic,” said assembly member Rick Chavez Zbur.

Zbur and fellow assembly member Dawn Addis co-authored Assembly Bill 1468, which proposed more stringent oversight over how the subject would be taught and the restriction of material to “domestic” experiences. The bill was pulled by its authors last month and replaced with a new bill focused on targeting antisemitism in schools.

Zbur, a Democrat, is adamant that his critiques and policy aims have nothing to do with events at the national level. “This is completely separate,” he said. “I wouldn’t even put this in the bucket of things that the federal administration is focusing on.”

Academics and policy experts see things differently. To them, ethnic studies is becoming another flashpoint term with academic origins – not unlike critical race theory (CRT) – being used to quash the teaching of subjects like colonialism and racism.

“It’s using the language of civil rights to go against civil rights,” said Rachel Perera, a fellow at the Brown Center on Education Policy at the Brookings Institution. “It all seems very similar to trends we’ve seen nationally.”

Ben Olinsky, senior vice-president of structural reform and governance at the Center for American Progress, echoed her point. “You have to view all this within a much broader push to censor opposing voices by Trump and folks on the right.”

The ethnic studies drama also builds on trends that first emerged during pandemic-era lockdowns and the racial reckoning that followed the murder of George Floyd. Many parents saw what their children were learning in school over Zoom and were unhappy about the content. Rightwing politicians have seized on this, turning what began as local cultural disagreements into a “parents’ rights” movement that seeks to mute the discussion of certain topics – such as race and gender – in schools.

“Rightwing groups have a stranglehold on our electeds,” said Gallagher-Geurtsen, claiming the California lawsuits are the product of a rightwing political engine intent on quashing free speech and weakening anti-racist efforts. “This is precisely the moment to step up and show white nationalists that they will not win.”

When it comes to the Jewish parents’ antisemitism allegations, she rejects them out of hand. “Are you referring to white supremacist folks who don’t want us talking about race and racism?” she asked.

Lerman, who represents Jewish families in several lawsuits, paints a very different picture – one in which progressive parents who want to protect their kids from harassment are being cornered and maligned as hateful racists. In reference to parents who have moved schools as a result of the conflict, she said: “These are liberals who went to live there because they believed in living in a diverse society, because they’ve upheld civil rights for so long, and suddenly their children are being bullied and humiliated and put in a position that’s just untenable,” she said.

It is unclear whether there is a middle ground in this battle of opposing worldviews, where each side is convinced the other is perpetuating harmful and discriminatory ideas.

The result of such rancor is that the quality of public education goes down, experts say. Teachers, fearing retribution, are silenced or leave the profession entirely; parents with means move their kids to private schools; and school districts see much-needed funding disappear. “These events are going to shape how educators talk about and teach these topics that they know are politically contentious,” said Perera.

Perera thinks that the dissolution of America’s public school system, which shapes the minds of 80% of the nation’s K-12 students, is a goal of the Trump administration’s war on education. “That’s the end game: to dismantle the public education system by sowing distrust and creating poor experiences.”

Experts also fear that the infighting and its focus on Israeli politics distracts from what they see as a very real, and growing, threat of antisemitism, especially on the right. “It is really hard to take Trump and his administration seriously on this issue when one of his senior advisers gave a Nazi salute and they seek to weaponize the label of antisemitism to silence protected free speech on campuses,” said Olinsky.

Added Kitonga: “Antisemitism is a real and scary phenomenon. Coming for ethnic studies will not resolve any bit of it.”

3 hours ago

1

3 hours ago

1