It’s just gone 3pm on a sunny Wednesday in Norwich, and the mid-afternoon, midweek slump is hitting hard at the cafe on Dereham Road. Almost everyone here is asleep – before they’re roused by the rattle of the Dreamies tub, that is. The Cat House, which opened nearly two years ago, is the city’s first cat cafe. From Wednesday to Sunday, for a cover charge of £10, punters can spend 60 minutes (or £13 for 90 minutes) enjoying feline company over a beverage and a snack. There are a few people already here – as well as the 20 resident cats dotted around the spacious converted building. They’re curled up above eye level in cat trees, hunkering in boxes and tunnels, weaving in between the table legs. The visitors hover respectfully in their orbit, hoping to be favoured by their attention. From the hushed voices, sound of the water fountain, and nature scenes playing on the TV, the Cat House resembles a library more than a cafe. There’s no clue to the controversy about whether it should be in operation at all.

Two months ago, the RSPCA and Cats Protection made a joint call for cat cafes to be phased out, saying that it was “almost impossible” for them to guarantee the animals’ welfare. Once a novelty, the concept has become relatively common in the UK, and not just in big cities. According to a freedom of information request lodged by the RSPCA and Cats Protection, there are 32 cat cafes licensed across England (and none in Wales). With 44% of those licences granted in the last financial year, their number may be set to rise further. Not all areas require licences, meaning the charities also suspect more are operating without any oversight. The sudden increase in cat cafes has led both organisations to take a joint stand, calling on local authorities to decline applications for new licences and not renew existing ones.

Alice Potter, a senior scientific officer and cat welfare expert with the RSPCA, says the organisation is not solely motivated by the lack of regulation, or the risk of unscrupulous operators. Key to its concerns is the potential for stress from the confined environment, exacerbated by the presence of other cats as well as customers. Though Potter acknowledges that practices “vary greatly” between establishments, there’s no getting around those fundamental challenges, she says. “Cats are just not built to live in cafes … There’s only so much space and freedom they can give.”

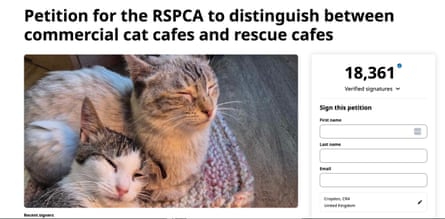

For cat cafe proprietors, however, the campaign lacks crucial nuance – and seemed to come out of nowhere. “I was shocked, to be honest,” says Tasmin Hirst, co-owner of the Bad Cat Cafe and Rescue in Wallsend, North Tyneside. She started a Change.org petition calling on the RSPCA and Cats Protection to distinguish between commercial cat cafes, run for profit, and those that operate primarily as rescues. It now has nearly 19,000 signatures.

Her own venture is intentionally small-scale, home to only eight cats at once, with the aim of finding them permanent homes. When we speak, the cafe has only six felines after two were rehomed the previous day. It is barely even a cafe, Hirst says: “Ours is run more like a shelter, where we sell food and drink to raise funds for the cats.” The venue’s name is tongue-in-cheek, she explains, intended as a playful way of managing customers’ expectations should the cats not be forthcoming.

Most of the new arrivals come from local shelters that are at capacity, or owners who are forced to relinquish their pets. Hirst says the cafe is also typically able to take bonded pairs or small groups, which shelters might have to split up. “We quite often take in cats that the RSPCA and Cats Protection have said no to,” she adds, noting the irony. The cats that don’t like or aren’t suited to the environment are placed locally in foster homes – but “being in the cafe is a lot better for them than being in a cage”, she says. For prospective owners, too, it’s a more relaxed way of meeting potential new pets. “We get to know them so well, we can identify suitable homes … and there’s a bit more peace of mind, because we say we’ll take the cat back if there’s a problem.” She estimates that cats are with the cafe for eight weeks on average – and that, in two-and-a-half years, the Bad Cat Cafe has helped 150 felines into new homes.

Hirst has concerns about more commercial operations, and licensing. “We get the same licence as pet shops used to get, when obviously it’s a different concept. I’m not against more regulation, or inspections.” But she worries that the criticism from the RSPCA and Cats Protection, “unfairly … lumping all cat cafes as one entity”, will negatively affect her operation. A few days before our call, the cafe’s window was keyed. “It could just be kids – it was the school holidays – but equally it could be someone who’d heard that cat cafes are bad,” Hirst says. “People do still listen to the RSPCA and Cats Protection, especially older generations – I don’t like how it’s going to affect the public’s perception of us.”

Some may still be catching up on the concept of cat cafes altogether. According to the BBC, the first cat cafe opened in 1998 in Taipei, Taiwan, with just five street cats. When the idea reached Japan in the early 00s, it took off with young professionals prevented by small apartments and strict leases from having pets of their own. Vice reported that 79 cat cafes opened across Japan from 2005 to 2010. Four years later, a pop-up cat cafe opened in New York as a marketing stunt by the pet food brand Purina One – then, in 2015, “cat cafe” was added to the online Oxford Dictionary. Their steady spread – through the US, UK, Middle East and Europe – coincided with the rise of social media, placing a new premium on novelty, visual spectacle and “experiences” to post to Instagram. Cat cafes often draw in punters with exotic breeds, photogenic backdrops – and the promise of a photo op. “While the majority of those who own, work in or visit cat cafes undoubtedly care for the animals, the sad reality is these spaces could be putting people’s enjoyment before the welfare of the cats,” says Elizabeth Mullineaux, president of the British Veterinary Association, which supports regulation.

Lucy Hoile, a feline behaviourist, agrees that they are rarely “an ideal environment” for cats and their complex social needs. The perception of them as antisocial loners isn’t quite accurate: they can form strong bonds and social groups, but ideally, “they’d have that freedom to avoid each other, if they want to”, Hoile says. “And the nature of a cat cafe doesn’t really give them that opportunity.”

The best-case scenario, Hoile suggests, would be a venue built around a “well-established, stable group of cats who really love each other” – but that is not what she has observed at the handful she’s visited as a punter. “There’s a lot of cats that are just making do,” she says. “They’re not attacking people or having huge fights … but there’s lots of subtle stress signals you can see, like hiding away and pretending to sleep.” That stress will make them more susceptible to illness as well as unhappy, says Hoile – but the signs aren’t always easy to spot, even for experienced cat owners.

She is sympathetic to those cafe proprietors who are motivated to help and celebrate cats. “It must be so difficult to find the right combination of cats, and to set that up for success,” she says.

Sarah Price, owner-manager of the Cat House in Norwich, believes she’s managed it with her resident group of 20. To see them, lined up together for treats, it’s hard to believe that they’re all the same species. There’s Romeo, an enormous blue-grey maine coon with a lion-like face, whose ears nearly reach knee height. Khamoon, the hairless sphynx, with piercing grey-blue eyes and skin that feels like suede. Augustus Le-Blanc, AKA Gus, a creamy-orange ragdoll who is described as “nice but dim”. None of the 20 are available for adoption – but Price laughs off the suggestion that that makes the Cat House a primarily commercial venture. “Business is secondary,” she says, over a mug of tea that reads BEST CAT MOM EVER. “I do it for the love of cats.” We’re seated on the outdoor “catio”, under the observation, from the highest rung of the nearby cat tree, of Lily the Lykoi (or “werewolf cat”, for their somewhat moth-eaten appearance. Nonetheless, she is not without charm).

Though Price often highlights cats needing new homes on the Cat House’s social media pages, she says she would “never consider” rehoming directly from the cafe: Today’s group has been assembled carefully over time, mostly as kittens, which fit in easier than older cats, Price says. Even so, three have been rehomed because they weren’t a personality match, or otherwise disrupted the balance. One, a 10-week-old kitten named Obi, went home with Price, joining her family pets, after he took to haranguing Nellie, Dot and Pearl, a trio of jet-black sisters. “We took him out of the mix, and everything went back to normal.”

Prior to the pandemic, Price worked in care homes, running music workshops. She imagined the Cat House as a sort of community arts centre, with resident cats – reflected now in its regular programming of art classes and craft workshops, all cat-themed. In late 2021, over a five-day road trip, Price visited 10 cat cafes and “learned that I didn’t want to do what they were doing”. Some were on high streets or in shopping centres, with no outdoor access and continual disruption from passersby; others seemed to prioritise the cafe above the cats, serving proper meals, not just snacks. It was clear that many cats weren’t thriving, Price says. “There were lots that were very timid and really didn’t want to be touched. You know when you go to stroke a cat, and they arch their back away? A lot of that was happening.”

The Cat House opened in August 2023, after a long search for a sufficiently spacious, one-storey venue off the high street. Ensuring peace and harmony on the premises is a constant process of observation and adaptation, Price says. Each cat receives daily grooming, a weekly health check and monthly weighing, meaning there are regular opportunities to check for concerns, signs of stress or changes in mood. There is also extensive record-keeping to ensure consistency and communication across staffing changes – including a 20-point checklist for each cat. “We write down any incidents – such as: ‘Roxy growled at Pearl’ – because it’s important,” says Price.

There are rules for customers, too – chief among them, no feeding the cats or picking them up. The free-form “lounge sessions” are restricted to ages 10-plus, and 20 customers at a time, but there are regular supervised “cat awareness sessions” for younger children to learn how to respectfully interact with cats.

Price says she “wasn’t worried” by the RSPCA and Cats Protection report. She too has noticed the rapid, recent increase in cat cafes, even in Norfolk, and believes that some would be best shuttered. “But I just think it needs to be monitored more.” Presently only some local authorities in England and Wales require cat cafes to be licensed and regularly inspected. Those that do tend to use regulations more typically applied to dog breeders, dog daycare and boarding kennels and catteries – so considerations specific to cat cafes can be lost. Instead of phasing them out, Price says a point-based system could be created to prevent them from being opened in high-density areas, to cap cat numbers and account for beneficial factors such as outdoor access and environmental enrichment. “How much space have you got per cat? ... How big is your building? Can they climb?” says Price. Cat cafes could also be reimagined as add-ons to shelters or sanctuaries.

But for the RSPCA and Cats Protection, the concept is not worth fighting for. They are urging the UK and Welsh governments to identify and stop all activities “that negatively affect the welfare of animals” as part of their review of licensing activities later this year. (Cats Protection has also specifically requested an end to “cat yoga”.)

Potter points to the disagreement, even among cat cafe owners, over which approach is better for welfare – those with resident cats, or those that rehome them. “There are issues on both sides,” Potter says, “which is why we don’t think cat cafes are suitable for cats, full stop.” It may be possible to design and operate a venue that consistently meets all animals’ welfare needs, “but I think it’s very unlikely”, she says.

Hoile agrees. “We should be aiming for the best, for every cat … and it’s a hugely complicated area to get right, if we do stick with it.” There’s perhaps a fundamental tension, she suggests, between cats’ needs for escape routes, hiding places and plenty of space, and customers’ expectations of coffee with a side of cuddles. “You wouldn’t pay to go to a cat cafe and leave without seeing a cat.”

5 hours ago

3

5 hours ago

3