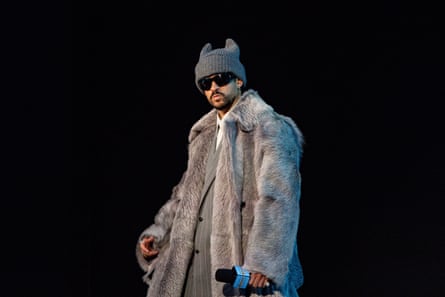

A few days after Christmas 2022, Bad Bunny, the Puerto Rican reggaetonero, appeared without warning on one of the most unlikely of stages: the roof of a Gulf Oil gas station in San Juan. To a massive crowd singing every word, he performed a surprise concert, along with friend and collaborator Arcángel, that was part hype-y music video shoot, part exultant post-tour homecoming, and part pointed critique. He ended the set with El Apagón (“The Power Outage”), a clubby protest anthem about local displacement and the rolling blackouts that have plagued Puerto Rico, a US “commonwealth” (read: colony), since Hurricane Maria in 2017.

Bad Bunny sang it from a roof on Santurce’s Calle Loíza, a thoroughfare in a former working-class Black neighborhood now dotted with Airbnbs. But you do not need the full context to get the show’s contagious energy. Though I have never walked Calle Loíza, nor do I speak Spanish, the gas station show is still my favorite concert to rewatch via online fan clips: electric, organic, genuinely popular. In terms of reach, critical acclaim and longevity, Bad Bunny rivals – and sometimes outsells – the likes of Taylor Swift, Kendrick Lamar, Beyoncé and Drake, though it is hard to imagine those peers appearing so unguarded, so public, as he does on that roof.

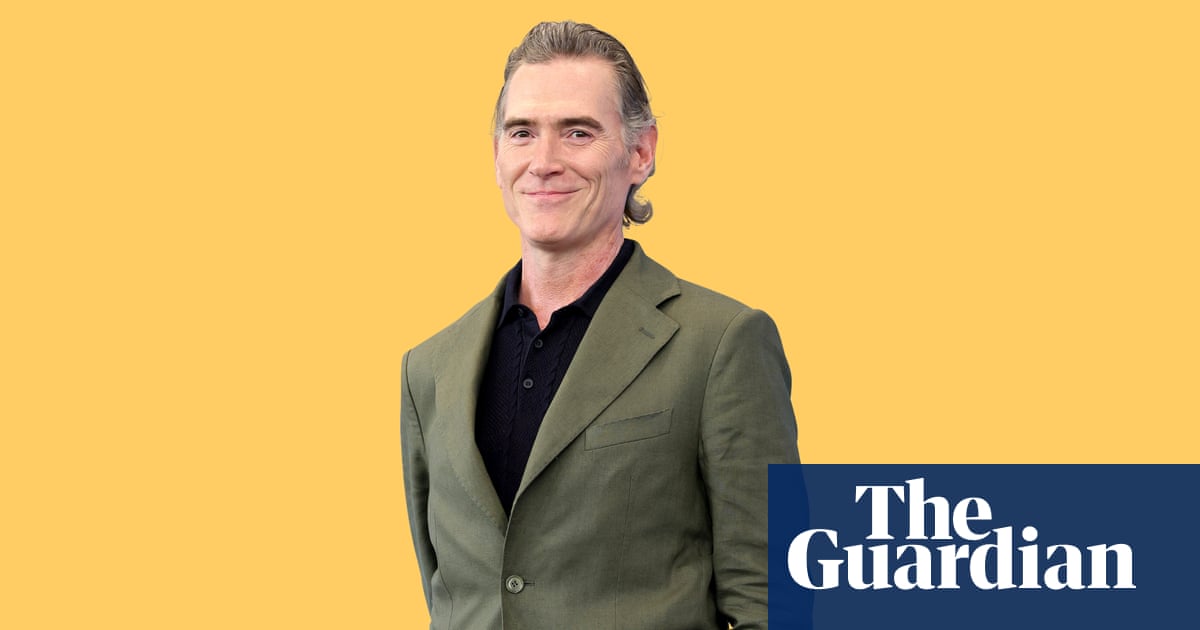

That particular combination of pure charisma, irreducible identity and undeniable beats has propelled Bad Bunny, born Benito Antonio Martínez Ocasio, to the height of global superstardom, transcending language barriers to a heretofore unseen degree in the continental US. His genre-smashing music – all in Caribbean Spanish – flows everywhere from New York street corners to my parents’ kitchen in suburban Ohio, projected and celebrated on a series of bigger and bigger stages: a record-setting US arena tour in 2022, including two sold-out nights at Yankee Stadium. At Coachella in 2023, where he became the first Spanish-language headliner, opening atop a replica of that Gulf gas station. At the Grammys, where just last week he became the first Spanish-language artist to win album of the year, for his homecoming opus Debí Tirar Más Fotos (“I Should Have Taken More Photos”). And on Sunday, he will step on to the biggest stage yet of his career: the Super Bowl half-time show.

That a Spanish-language artist will occupy one of the vanishingly few monocultural venues left in the polarized US feels inevitable yet still improbable. Inevitable, in that Bad Bunny has been the most-streamed artist in the world for four of the past five years, and has broad appeal in the US, where there are about 55 million Spanish speakers – the second-largest population in the world, behind only Mexico. “From the business standpoint, it almost wouldn’t make sense for it to be anyone other than Bad Bunny, especially in a moment when the NFL is trying to reach both global audiences and younger audiences,” said Perry Johnson, a music scholar at work on a cultural history of the Super Bowl half-time show. Improbable, in that the Trump administration has so fiercely demonized Hispanic immigrants and so thoroughly politicized Spanish, that choosing a Spanish-speaking performer seems like an uncharacteristic risk for a brand-safe corporation like the NFL.

Unsurprisingly, given that Bad Bunny – an American citizen, as are all Puerto Ricans – skipped the US on his DTMF tour to protect Spanish-speaking fans from Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), the announcement was immediately met with hostility by members of the US government.

“It’s so shameful that they’ve decided to pick somebody who just seems to hate America so much, to represent them at the half-time game,” said the homeland security adviser Corey Lewandowski. The homeland security secretary, Kristi Noem, promised that ICE would be “all over” the Super Bowl. In protest, Turning Point USA, the rightwing organization founded by the late conservative activist Charlie Kirk, has planned an alternative “All-American Halftime Show”, starring Donald Trump ally Kid Rock and hyped by JD Vance.

Bad Bunny has promised a “huge party” where, according to the jubilant trailer, “the world will dance”. But no matter the quality of the music (and for the record, it is very danceable), the symbolism of a Puerto Rican performer of Spanish-language music on the biggest stage in US pop culture has already exceeded the show itself. The show “has become more about politics than about music”, said Yarimar Bonilla, the director of the Center for Puerto Rican Studies at Hunter College.

“His very presence on the stage is a statement,” said Petra Rivera-Rideau, co-author of the book P FKN R: How Bad Bunny Became the Global Voice of Puerto Rican Resistance. “The fact is that we’re currently in a moment where Spanish is seen as a mark of being foreign, of not belonging, where people are getting profiled for being Spanish speakers – that ups the ante and importance. It can’t really be overstated.”

Intentionally or no, Bad Bunny has found himself at the center of polarized America’s perpetual culture wars, playing out once again at the most American of entertainment spectacles, the Super Bowl – where, as Johnson says, “ideas around patriotism, citizenship and Americanness get played out”. American football remains freighted with ideas of respectability, race, good old boys. And since the first Super Bowl in Los Angeles in 1967, the half-time show has served as a staging ground for ideas of what does or does not represent “America”.

It has thus courted backlash, especially along lines of race and gender – think the disproportionate furor over the infamous exposure of Janet Jackson’s bare breast in 2004. Complaints to the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) spike with every Super Bowl, especially as the interests of a white, conservative minority clash with the business interests of the NFL and the public’s preference for the now-global sound of hip-hop. (And especially since Jay-Z’s Roc Nation controversially took over the half-time show in 2019; since then, there have been no white headliners, and viewership has surged.) There was white discomfort with Beyoncé’s Black Panthers costumes when she took over Coldplay’s 2016 half-time show with Formation (as memorialized in the SNL skit “The Day Beyoncé Turned Black”.) There was backlash to Shakira and Jennifer Lopez, two Latina women over 40, when they performed in English in 2020; backlash to Dr Dre and friends in 2022, with FCC complaints of “reverse racism”; backlash last year to Kendrick Lamar, whose invocation of mass incarceration and anti-Black racism drew 133.5 million viewers, the most of any Super Bowl half-time show ever.

A Spanish-language performer, even a hugely popular one, supercharges all of this, especially when the administration is deliberately targeting and terrorizing predominantly Spanish-speaking undocumented immigrants. Objection on grounds of “foreignness” or “un-Americanness” – even and especially for Latino US citizens – “happens whenever you have a Latin artist on a stage that’s considered very patriotic”, said Rivera-Rideau. In 1968, the Puerto Rican-born, Harlem-bred musician José Feliciano performed a Latin guitar-tinged national anthem in English at the World Series – only to face calls for deportation that nearly derailed his career. (In a full-circle moment, Bad Bunny brought out Feliciano at Coachella.) When Marc Anthony, a New Yorker of Puerto Rican descent, sang God Bless America at the MLB All-Star game in 2013 – again in English – he was met with a string of social media abuse. One Twitter user wrote: “Shouldn’t an AMERICAN be singing God Bless America? #getoutofmycountry.”

The Turning Point USA half-time show – a “family-friendly, values-driven” event “created for viewers seeking uplifting, patriotic entertainment” – boasts a pop-country lineup that will sing “anything in English”. The phrase echoes the “English Only” movement of the 20th and 21st centuries, an effort to adopt English as the only official US language with thinly veiled anti-immigrant and anti-Latino sentiment.

The backlash to Bad Bunny is part “of a very old story”, said Frances Negrón-Muntaner, a Puerto Rican film-maker, scholar and author, one which positions Latinos “as foreign, as unassimilable, as people who somehow do not and cannot contribute to American life – even though, factually, that’s not true at all”.

From the beginning of his career, Bad Bunny has spoken directly to the purgatorial status of Puerto Rico, which has been a US territory since 1898. (The terms are deliberately confusing – as one defining supreme court case put it, the archipelago paradoxically “belong[s] to the United States, but [is] not a part of the United States”.) He has sponsored billboards in Puerto Rico against US statehood. On DTMF, he mourns Lo Que le Pasó a Hawaii – “what happened to Hawaii”, which became a state in 1959 and is now a tourist haven that has utterly marginalized the native population. Last summer, his landmark 30-show residency at San Juan’s Coliseo de Puerto Rico partnered with local hotels to put off Airbnb-ers, prioritized local affordability and kept the first nine shows available only to island residents.

But the hyper-specificity of Bad Bunny’s music and persona – the references; the unique frustrations; the slang that is, as Bonilla wrote, “full of so many skipped consonants, Spanglish, neologisms and argot that it borders on Creole” – has not blunted its appeal. If anything, the issues that he sings about (success, partying and women, yes – but also mass tourism, gentrification, the pressure to leave and the desire to go home) resonate in the US and beyond. His lyrics “go to the essence of something”, said Negrón-Muntaner. DTMF standout Nuevayol, for example, takes its name and themes from the Boricuan pronunciation of Nueva York, but “even if you’re Mexican or Colombian or Venezuelan or Peruvian or wherever in Latin America, you know what Nueva York is,” she said. “It’s like your version of New York – the immigrant version of New York.”

It’s no surprise, then, that US conservatives, who take a hard line on immigration and lump anyone speaking Spanish into one massive “other”, have conflated Bad Bunny’s Puerto Rican-ness with the incoherently amorphous category of “Latino”. Arguably so, too, has the NFL, which is banking on Bad Bunny’s popularity to help its expansion outside the US and with its fast-growing Latino audience at home. Just as Hollywood sees its future in Asia, the NFL recognizes that “they need to compete at a global scale,” said Negrón-Muntaner. “And if you want to do that, then you want the biggest global star available.”

Bad Bunny, usually reticent to take on a position foisted on him, alluded to all that baggage and conflation at the Grammys. Accepting the award for best música urbana album, he said, uncharacteristically in English: “ICE out! We’re not savage, we’re not animals, we’re not aliens. We are humans and we are Americans.”

Whatever he actually meant, “I think what landed was that Latinos who are here and trying to build a life, or who have been born and raised here now for generations, should also be considered Americans, for purposes of rights and responsibilities,” said Negrón-Muntaner.

His comments were naturally met with a new round of performative outrage from the Maga chattering class. (I am loath to quote, but here’s Megyn Kelly: “I feel like we might want to send ICE down to his compound. He’s worth a hundred million dollars, reportedly.”) The backlash “is communicating traditional ideas rooted in white supremacy and English speaking”, said Johnson, though the NFL understands that “they will be able to capture audiences who, were it not for Bad Bunny, would not otherwise be tuning in, and there’s immense value in that.” For Maga, said Bonilla, “the fact that the top artist in the world is Spanish-speaking, is American with an asterisk, is not their definition of America, stokes their fears of what America is becoming, and the irrelevance of other forms of American-ness on the global stage.”

There is a double-edged element to that, even from those eager to embrace Bad Bunny as a symbol of anti-Trump resistance writ large. “I see so many people on TikTok brushing up on their Spanish, learning the lyrics to the songs, and self-described gringos saying like, ‘OK, I’m going to learn.’ And there is something really beautiful in that,” said Bonilla. “But at the same time, I feel like the specificity of him as a colonial citizen, as someone who has been fighting not for greater rights within the US, but the right to forge our own path, has gotten lost in the messaging.”

Migration, melding, shifting tides of influence and power – in their own ways, Maga and Bad Bunny are responding to the same 21st-century phenomenon: the detachment of culture from geography, leaving many people, regardless of physical location, feeling at once adrift and hyper-connected. The dark vision of Maga – one of strident identity protectionism – continues its culture war on all that it deems threatening, different or conveniently worthy of scapegoating. But no matter how Sunday’s performance goes, Bad Bunny, an uncompromising musician who has made an art of interconnection and a meal of expectations, has already won. “It’s going to be fun. It’s going to be easy,” he promised on Thursday, days ahead of the show. Backlash or no, the party goes on.

2 hours ago

3

2 hours ago

3