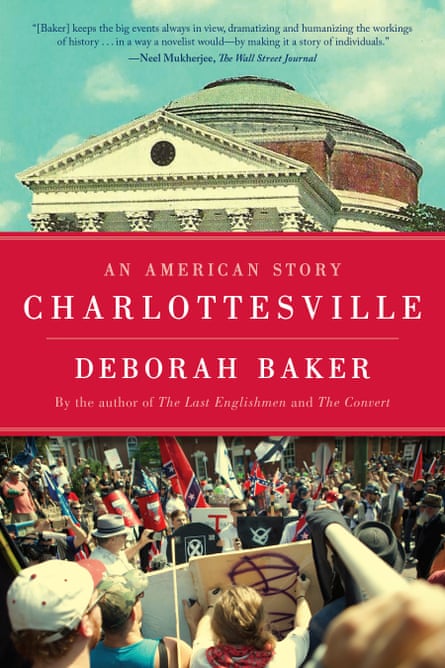

Deborah Baker’s new book, Charlottesville, is about her home town in Virginia, where in summer 2017 white supremacists marched, violence erupted and a counter-protester was murdered. In dizzying detail, Baker charts and reports the chaos. In interludes, she examines the dark history of a city long linked to racist oppression, from the days of Thomas Jefferson, Robert E Lee and slavery to the rise of the Ku Klux Klan and resistance to civil rights reform.

Putting it all together was a new challenge for a writer whose books include In Extremis, a biography of the 20th-century poet Laura Riding, and A Blue Hand: The Beats in India.

“As a literary biographer, a narrative nonfiction writer, I mostly work out of archives and libraries and letters and diaries and things like that,” Baker said. “And of course, for this, there wasn’t anything like that in a library or institution. So I had to make my own archive, which involved the interviews I did with around 100 people but also old Twitter streams.”

Many such streams were shot by progressive protesters and citizen journalists who rallied with local clergy and citizenry against the white supremacists, neo-Nazis, Klansmen, militiamen and alt-right provocateurs who descended on their town.

They came because the city government had voted to remove statues of Lee and Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson, slave-owning Confederate generals who lost the civil war – a reminder that national debate over racism and US history long predated the police murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis in 2020 and the turmoil that followed.

As Baker shows, tensions flickered and spat in Charlottesville for months, the town riven by internal disagreements, democracy playing out its messy truths in endless rallies and meetings about what to do with the statues and the version of history they told.

Then came the night of 11 August, when khaki-clad white men carrying tiki torches chanted “Jews will not replace us” as they marched to the Lee statue. The next day, a “Unite the Right” rally produced hours of frenetic face-offs and the awful moment when a white supremacist used his car to drive into counter-protesters, injuring 35 and killing one, Heather Heyer, a 32-year-old paralegal.

“The prospect of talking to not just living people, and asking them questions about this deeply traumatic event in the center of their lives just made me quail,” Baker said. “It’s one thing reading people’s private letters and diaries, and especially dead people. It’s completely different when you’re actually faced with a person, someone who’s half your age, who’s grown up in a world that’s as foreign to you as India might be to an American.”

Baker is 66. Many of those who marched against the right in Charlottesville, if by no means all, are 30 years younger or more. Writing their stories meant understanding their worldviews.

“I was just learning about the parameters of an online existence that was very unfamiliar to me,” Baker said. “Luckily, I had people who were very patient with my learning curve.

“I didn’t know what this historical period was. It was very hard for me to understand the present. I thought certain things were assumed. You know, that Nazis were bad. We figured that one out, I thought. I guess you have to keep refreshing that narrative.”

Married to the writer Amitav Ghosh, Baker lives in Brooklyn and India. But as the subtitle to Charlottesville says, in writing about her hometown she also set out to write “An American Story”, particularly about the rise of the far right under Donald Trump.

When she started work, in the first days of 2021, Trump had been beaten by Joe Biden. It seemed the far right had reached its high-water mark: the deadly January 6 attack on Congress. But many traced paths from the Capitol back to Charlottesville, particularly to the moment when Trump failed to disown the rightwingers who marched in his name.

Baker writes: “For those watching around the world, Charlottesville’s fate as the global synonym for ‘white supremacy’ and ‘white nationalism’ was sealed when the president of the United States declared there were ‘very fine people on both sides.’

“He doubled down several days later to describe the violence of an imaginary ‘alt-left’ … Trump’s remarks seemed to open the gates of hell. The next 18 months saw a surge in white supremacist violence across the country.”

Trump left office but far-right violence continued. Trump didn’t leave the stage either. Seven years after Charlottesville, he is back in the White House, attacking anything in government seen to even acknowledge the US’s racist past, using claims of “white genocide” to import white Afrikaners.

“American democracy was failing the whole time I was writing,” Baker said, “and I didn’t realize that it could fall that much further. And obviously it’s falling very fast now.”

She notes how police violently broke up pro-Palestinian protests at the University of Virginia (UVA) in Charlottesville last year, aggressive behavior in stark contrast to restraint shown to the white supremacists who marched eight years ago.

She wonders about the effect her book might have on people “that didn’t quite register what happened in Trump’s first term, and about the sense of deja vu not only with 2017 but also these other periods of history which we have conveniently forgotten or swept under the rug, whether it’s the Klan or the White Citizens Councils”, groups that sprang up in the 1950s, in opposition to attempts to end segregation.

In the historical sections of her book, Baker considers famous figures including Lee, Jackson and particularly Jefferson, who lived at Monticello above Charlottesville and designed the UVA campus.

She also provides studies of some now forgotten. Prominent among them is John Kasper, an esoteric young demagogue, close to the fascistic poet Ezra Pound, who staged cross burnings in Charlottesville in the 1950s. Kasper died in 1998, long bypassed by history. But as Baker studied the resurgence of a far-right threat she had thought long buried, so she sensed echoes including something of Kasper in the polished figure of Richard Spencer, the “alt-right” leader who achieved a sort of national prominence around events in Charlottesville in 2017.

“They’re like doppelgangers,” Baker said. “You know: knee-jerk contrarianism, superficiality, really just hunger for fame and attention.”

Spencer also saw his star fade. The Lee and Jackson statues, and other contentious Charlottesville monuments, finally did come down.

The statue of Lee and his horse, Traveler, is “the only one that has been actually destroyed,” Baker said. “The rest of them are all in storage rooms, or they’ve been moved to battlefields. I’m glad this one is gone. It really is due to this group of Charlottesville women who were very set on not just melting it down and destroying it but set out to make some new kind of art and give to the city.”

One day soon, via the Swords Into Plowshares project, the bronze once used in the statue of Lee will form something new.

Baker is under no illusion that the far right is defeated. Four months into Trump’s second White House term, she is “surprised that I haven’t seen more violence already”.

“I think there was a kind of giddiness when he was first elected,” she said, describing “a sense that they had their presence. They did these marches for Trump. They had their boat rallies. They had their truck rallies. They had their guy.

“There hasn’t been as much of that so far this time. That isn’t the form that it’s taking. Maybe they just don’t feel like they have to be so active.”

-

Charlottesville is out now

1 day ago

25

1 day ago

25