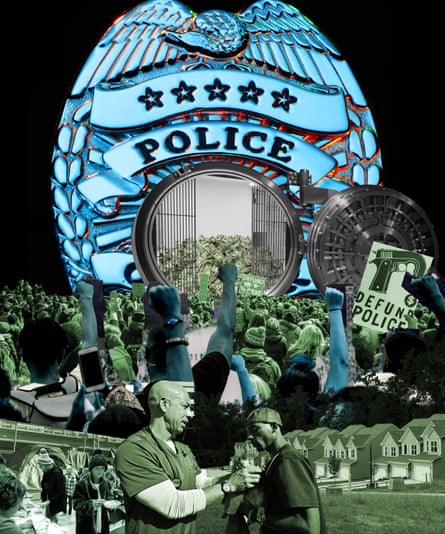

After George Floyd’s murder by a Minneapolis police officer in 2020, protesters who swarmed the streets across the US shouted the refrain: “Defund the police.” An idea that was once viewed as radical – to redirect money from law enforcement to other city departments and social services – became a rallying cry overnight.

As a result of continued pressure, dozens of jurisdictions throughout the nation promised to reduce their police budgets. While most of them backtracked and increased law enforcement funding in the next year or two, several cities changed policies or added new public safety and homeless services departments.

Milwaukee is one city where leaders diverted money to social programs that had a lasting impact: funding from the police department went toward affordable housing and youth programming. After 2020 Seattle invested part of its police funding into participatory budgeting, a process in which the public votes on how to spend a portion of the city’s finances.

A few years later, inspired by calls for alternatives to policing from Black and brown organizers, Seattle leaders launched a third public safety department that responds to mental health crises. And Austin has increasingly invested more money in its homeless services since the city diverted millions of dollars from the 2021 police budget to go toward permanent supportive housing instead.

Political organizers the Guardian spoke to said the abolitionist dream of divesting from police and reinvesting in social services is a long journey full of valleys. Backlash followed the 2020 protests, and public sentiment toward the movement quickly shifted.

According to a recent Pew Research Center survey, 27% of respondents said greater attention to racial inequality in the US improved Black people’s lives, compared with 52% who said it would lead to positive changes in 2020. Though the success stories of the defund movement are not always clear, the groups behind it say they helped move the needle forward in sparking conversations about city priorities and reimagining what public safety looks like. They hope the Trump administration’s commitment to capital punishment and increasing law enforcement will inspire people to again envision alternatives to policing.

“If spending money on policing were an effective way to deter crime, then the United States would be the safest country on the planet that has ever existed and it is nowhere near that,” said Marcus Board, an associate professor of political science at Howard University. “Meanwhile, healthcare suffers, childcare suffers, elder care suffers, public spaces are going away.”

Instead of recognizing that people need a social safety net, he said, society punishes people for their hardships as if it’s the key to transformation. But the punishment also robs people of their agency.

“That’s a world that will constantly suffer unless people step up to do something,” Board said, “which is why it’s so important to remember the movement for Black lives”.

‘A politicizing moment’

In the spring of 2019, Devin Anderson was tabling on police reform in Metcalfe Park in Milwaukee when an older Black woman approached him. Anderson, the campaign and membership director of the non-profit African American Roundtable, showed her a pie chart that revealed that 46% of the city’s general fund went toward the police department. Shocked by the figure, the woman told Anderson that she wanted to see more money spent on opportunities for youth, as she feared that boredom would drive her grandson to get into trouble that summer.

“That is a politicizing moment. Even if people do believe in police and policing, they don’t think it should be getting that much money,” Anderson said. “On a larger scale, what does it mean as a society when close to 50% of the money we spend has to go to police and policing, and it can’t go to make real investments into things that people want to see?”

Anderson and his team compiled the information that they gathered from tabling and listening sessions and formulated a list of community desires, including more youth programming, affordable housing and violence prevention. And then on Juneteenth that year, the African American Roundtable, which focuses on providing political education to the public, launched the campaign LiberateMKE to try to convince city leaders to divest $25m from the Milwaukee police department (MPD) and reinvest it in social programs instead. The campaign organizers attended budget hearings, spoke with city leaders about the need for reduced police spending and sent out email campaigns in which they encouraged residents to put pressure on their elected officials to invest more in social services.

A few months later, the campaign was somewhat successful: in Milwaukee’s 2020 adopted budget, the city diverted some $1.27m from the MPD to go toward housing and community services, and to increase the hourly wages for a summer jobs for youth program. Some of the diverted money also went toward affordable quality housing and a non-police violence prevention program, in which local residents were trained to de-escalate conflicts that had a high likelihood of resulting in shootings in their neighborhoods. In the city’s 2021 adopted budget, there was also an approximately $2m reduction in police funding, which the city’s comptroller, Bill Christianson, said reflected a smaller number of police officers, and that Anderson sees as a legacy of the group’s advocacy work.

‘A night and day difference’

Austin’s promise to cut its police funding worked for some time. The 2021 police budget went from $434.5m to $292.9m and some of the funds were invested into housing, healthcare, family and mental health services. But city leaders reversed course and increased the police budget to $443m the following year.

However, the impact from calls to invest in social services remains. After 2020, $6.5m that was diverted from the police budget went toward housing and services for unhoused people. Renovations for Bungalows at Century Park, an apartment community for the chronically unhoused that opened up last year, were included in that budget.

The residents pay for their apartments with housing vouchers or payment assistance and are meant to stay in their units long term, possibly for five or 10 years, said the director of Austin’s homeless strategy office, David Gray.

“To go from that into a safe, secure room where you can store your stuff safely, where you can sleep peacefully, and where you can meet with a case manager on site or get healthcare on site or job training on site, it’s a night and day difference,” Gray said.

While demands to invest in housing and services existed before Floyd’s death, the calls to defund the police that followed helped push discussions forward. Budget trends in recent years show that city leaders have listened to the community’s request for greater attention to the homelessness crisis. In Austin’s most recent point-in-time count of unhoused people from January, volunteers and providers recorded 1,577 unsheltered and 1,661 sheltered people – the first time that the count showed more people sheltered than unsheltered.

In the past five years, the city’s homelessness services appropriations have increased from $39.7m in 2020 to a proposed $118.1m in 2025. According to the city’s financial services data from 2024, the proportion of funding for homeless services that comes from the city’s operating budget has increased, from 49.7% in the 2023 fiscal year to 57.5% in the 2025 fiscal year.

“In the wake of Black Lives Matter protests this summer, we made a significant cut to policing dollars and reinvested that in things like this,” Austin city councilmember Gregorio Casar told the Appeal in 2021. “That’s the only reason we’re able to do this.”

Help outside of the police

Black and brown-led groups such as the policy organizing non-profit King County Equity Now and the Decriminalize Seattle coalition called on Seattle officials to establish a non-police crisis response unit. They presented the Seattle city council with a blueprint on how to divest from the police and reallocate funding to alternatives to law enforcement.

Organizers also called for a participatory budgeting process, in which the public would envision how to spend some of the city’s budget. And Seattle leaders listened to some of their demands: some $10.2m was diverted from the city’s police department to fund the participatory budgeting process’s overall $28.3m reserve in Seattle’s 2021 adopted budget.

Representatives from Seattle’s office of civil rights said that the funding from the police department came from unfulfilled positions and that the money would have returned to the city’s general fund if it were unused.

City leaders also looked to cities such as Eugene, Oregon, that had successfully launched non-police crisis response units to envision a third public safety department for Seattle. Launched in 2023, Seattle’s community-assisted response and engagement (Care) department is a 30-person unit consisting of 24 first responders who address calls throughout the city. Care operates 10 hours a day from noon until 10pm, with the top priority calls being for suicides and overdoses. In the last 16 months, Care has responded to more than 4,000 calls. The Seattle 911 dispatch was also transferred from the Seattle police department to the Care department.

When Care’s chief, Amy Barden, speaks to community members who have used the service, she said they relay to her that “it’s just a relief to feel like I can call 911, and get a different response” outside of the police. She knows that some health and social service providers avoid calling the police when their clients are experiencing mental health crises.

“They just don’t think it’s going to be useful in the circumstance, and that it can be stress inducing, no matter how skilled that officer is,” Barden said. “So it’s been a very popular movement across the board.”

Still, Barden views Care, police and the fire departments as working together as a team, and added that she “will not support divestment in the fire or police departments”, she said. “Relative to the 911 data, we desperately need more of everything.”

In 2024, participants in the participatory budgeting process – originating from the Black Lives Matter movement – voted to fund the Care department with an additional $2m to increase the number of the team’s behavioral and mental health specialists.

The organizers that helped push the city to create a third department say that Seattle can serve as an example for the rest of the nation. “It showcases the stronger need for us to always have these kinds of approaches to our work, particularly when we’re talking about doing work that’s supposed to benefit specific folks,” TraeAnna Holiday, the former media director of King County Equity Now, said. “It’s important for folks to be engaged and for them to have a vehicle that allows them to be involved when so many people are focused on survival.”

‘The movements are happening’

The protesters who took to the streets in opposition to law enforcement violence in 2020 were a catalyst for action, but the movement was ultimately led by organizers who worked for years to create safer and healthier communities.

The defund movement was sometimes demonized because there wasn’t a unified talking point on what communities would invest in outside of policing, said Hiram Rivera, the executive director of the Community Resource Hub for Safety & Accountability, a non-profit that trains communities on the basics of organizing.

During the mass protests, Rivera said: “Traditional organizing wasn’t happening at the community level; they weren’t able to build strong enough campaigns to either win the divestments or to be able to withstand the blowback when the pendulum swung in the opposite direction.”

Currently, Rivera said that the abolitionist movement is in a state of reflection on the past five years and assessing what they have the capacity to build, particularly given the federal attacks on non-profit organizations.

Rivera said that state bills have also made it challenging to divert funding from police departments since 2020. In May 2021, the Texas governor, Greg Abbott, signed a law penalizing cities for defunding their police budgets. And in Milwaukee, the African American Roundtable plans to end its LiberateMKE campaign over the next year due to an increasingly inhospitable landscape for defunding the police, Anderson said.

A 2023 state funding law called Act 12 allowed Milwaukee to implement a 2% sales tax and jurisdictions are provided with additional state aid for law enforcement and fire protection, among other departments. But the city will lose part of its state funding if it does not maintain its number of police officers at the same amount as the previous year.

In light of the Trump administration’s recent executive order on “strengthening and unleashing America’s law enforcement”, the Advancement Project’s deputy executive director, Carmen Daugherty, said she is hopeful that the public will demand community-based solutions. A 26-year-old civil rights organization that focuses on movement lawyering, the Advancement Project has helped grassroots groups pressure their cities to invest more in social services by analyzing city budgets, creating surveys and white papers, and launching campaigns.

“This administration is saying we need more policing, more military grade-style weapons in our communities to make us safe,” Daugherty said. “Once again, we’ll hopefully see that upswing and recognition in the spotlight on what these community groups have been saying since pre-2020, but really galvanized in 2020, that there’s more we can do. There’s smarter solutions to public safety.”

For organizers in the Black-led Movement for Black Lives (M4BL) coalition, they seek to dispel what they consider a false narrative that the rallying call around invest-divest didn’t work. The defund movement helped catapult the model from the advocacy space into the national dialogue, said M4BL’s interim senior director of communications, Chelsea Fuller. Every day for the past five years, she said an article about defunding has been published, or a politician has debated its merits.

“These types of changes in our communities very rarely happen overnight,” Fuller said. Movements take several years, or decades to accomplish significant change. “It’s not over. Five years in the legacy of movement work and liberatory work is a blip on the radar.”

4 hours ago

3

4 hours ago

3