In the mid-90s, Omaha made a pretty decent tour stop for up-and-coming bands. Nebraska sits near-plum in the US’s middle, and in its most populous city, once famed for its fur trade, stockyards and railroads, there had grown a thriving subculture that centred largely on a book and record store named the Antiquarium and a small venue named the Cog Factory.

Conor Oberst spent much of his early teens puttering between these locations, filling his young brain with music and literature. By 12, he had begun writing his own songs, and by 13 he had recorded his first album, releasing it on his older brother’s label and selling it in the record store. Sometimes he would take to the stage at the Cog Factory, a small, pale boy with an acoustic guitar and a lot of words.

He had already begun recording as Bright Eyes by the time the Texas band Spoon came through town. Oberst and his friends were huge fans, and turned up to the venue early to see the band arrive. “We loved Spoon,” he says. “But we didn’t know what anyone in the bands looked like, never seen their pictures. These vans pull up outside the club and you’re like: ‘I wonder which one’s the singer?’ There was a lot more mystery and fun to it then.”It would be another five years or so by the time Bright Eyes found success – by now a band rather than a solo project, they were widely feted for their fourth album, 2002’s Lifted Or the Story Is in the Soil, Keep Your Ear to the Ground, followed by their twin 2005 records I’m Wide Awake, It’s Morning and Digital Ash in a Digital Urn. By that time, the world was a very different place. Music and media were growing increasingly digitised, and the US was grappling with the presidency of George W Bush and the controversies of the Iraq war.

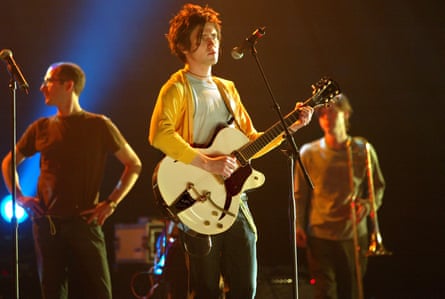

Oberst, whose songs were heartfelt and literate and politically engaged, carrying titles such as When the President Talks to God, became the poster boy of a new generation. His face was everywhere. When Bright Eyes’ tour bus pulled up at the venue, everyone knew he was the singer. “What happened to me wasn’t at all overnight because I had been touring since I was 15 years old, and at this point I’m 25,” he says. “But still, I think when that big push of fame or public persona, identity thing happened to me, it definitely affected me. I definitely felt the insanity of it.”

In many ways, the last 20 years of Oberst’s career have been an attempt to shake off that intensity and find the mystery and the fun of music again. “It is a hard thing to hold on to, that innocence, and what you loved about music sometimes,” he says.

Nevertheless, he has tried to grip tightly to that feeling; to remember what music is to him beyond a career. He learned the hard way, he says, that there is not much music in the music business. “But what I will say is music is consistently something that gives my life meaning, and is a source of solace and happiness – not just making it, but listening to it, and seeing people I love doing it,” he says. “Besides family and friends and loved ones, I would say it’s the most consistent thing in my life. There’s nothing else. I’m not religious, I’m not really a member of too many clubs or anything, it’s kind of just music that’s gotten me through it.”

The past few years have not always been easy for Oberst – there has been a divorce, the sudden loss of one of his brothers and, in late 2013, an allegation of sexual assault by a female fan. By the following summer, the allegations had been dropped, and the accuser had apologised both to Oberst and to “actual sexual assault victims”. It is not a time the singer is keen to revisit.

He speaks steadily, carefully, and gently declines to go on the record about the specificities of what happened. But one gathers that it led to the period he refers to now as “a time when I wished I never had made music, and wished no one had ever heard it. And that’s about the saddest feeling in the world when that’s your whole life, just wanting to not exist.”

What he will also say is that music played an integral part in helping him back out into the world again. “I go into music as a place to understand what’s going on. That’s a place that I know I can go that’s just for myself,” he says. “But it’s all in your mind, so it’s up to you to take care of it and tend the garden. And sometimes if you’re not feeling well physically or otherwise, or the world’s got you down, you stop weeding the garden and the next thing you know your mind’s just overrun and snarled. The forest takes over the grounds, and it’s pretty dark.”

Across the screen, Oberst looks small and bleary and slightly disoriented in his hoodie. “But you know, things tend to come back around and get better, and worse, and better again,” he says. “So it’s just trying to stay alive through those parts that seem insurmountable. And next thing you know I’m out here with some of my oldest, best friends in the world and everyone’s having fun,” he says, with a nod to the room behind him, a grey backstage space at the MegaCorp Pavilion in Newport, Kentucky, where Bright Eyes are on tour with fellow Omaha natives, Cursive. “This particular leg of this tour is probably the most old-school touring situation I’ve had for decades. It has been a relief of sorts to be travelling on tour buses again, hanging out till 4am, just fucking smoking weed in parking lots. Playing music. It’s great. It’s like nothing changed.”

Last autumn, Bright Eyes released their 11th album, Five Dice, All Threes. It is their most limber record in some while, capturing a kind of musical camaraderie between Oberst and his longstanding bandmates Mike Mogis and Nate Walcott. For Oberst, the record “definitely captures that sort of youthful punk rock spirit that maybe I’d forgotten about”.

He credits this rekindling in part to his friend Alex Levine, who helped in the writing of the songs at a point where the singer had “definitely lost interest in kind of everything”. “He was working at other studios with other people, and he’d come back and I’d still be sitting there on the porch, and he’d be like: ‘Why don’t we work on something?’ The first few times I was like: ‘Oh I’m good, man, let’s just sit around, I don’t care.’ And then he wore me down, and next thing we know we’re making demos. I think I really do have him to thank for lighting the fire.”

after newsletter promotion

The fire is not only musical. Oberst today seems once again politically ignited, railing against Elon Musk, the anti-immigrant crackdown, the dismantling of academic centres and legal processes, the attack on trans rights and the funnelling of public money into private contracts, against an administration he describes as “the greatest grift of all time”. It is a return of sorts to his earlier self: “I feel there might have been a period in maybe my early 30s where I was like: ‘I should, like, grow up. You shouldn’t be angsty towards the world. You should turn into this real acceptable thing that a lot of people can get behind,’” he says. “Because people like the idea of anger more than they like anger. They like the performative aspect. But the thing is, I really feel it. I really fucking hate these things and I always have, and it’s hard because I can’t not show it.”

Lately, at the band’s live shows, he has been encouraging his audiences to speak up. “The world is more fucked up and keeps getting more fucked up so I don’t think it’s time to act measured,” he says. “What I’ve been saying to the kids at the shows every night is you can’t wait. By the time you realise how bad it is, it’s too late, and that’s just something we know from history. Don’t wait till it’s cool to go down to the park and protest. There’s an alarm bell going off above our heads right now and we should all be screaming at the top of our fucking lungs.”

He thinks back sometimes to those teenage years in Omaha, when Rage Against the Machine were pretty much the only common musical ground he could find with the high-school jocks, and wonders whether any of them were aware that they were essentially listening to the communist manifesto. “But it slipped into suburban houses, and it did a public service ’cos it influenced all these people. It turned a bunch of them into political activists,” he says.

Each night, Oberst looks out from the stage into the crowd and sees a whole new audience before him, from little kids to an eightysomething woman there with her grandson, via people his own age, and “straight-up teenagers that could’ve been at a Bright Eyes show in 1999”. Somehow, amid all the darkness, he finds a hope in this crowd – perhaps even evidence of the role that music has to play in resistance. “I think music is magical,” he says, “I think it can cross all political lines.”

Bright Eyes tour the UK and Ireland from 16 to 25 June; tour starts Nottingham.

17 hours ago

4

17 hours ago

4