The protesters tore through the city chanting angry slogans and leaving a trail of destruction in their wake: shattered glass, broken doors and furious graffiti – “get out of Mexico.”

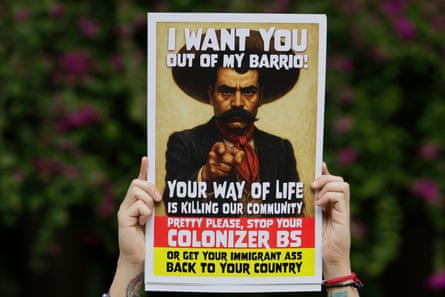

Some, dressed in black, smashed windows of local businesses. Others marched peacefully but carried signs with angry messages: “You’re a colonizer not a fucking ‘expat’”; “Gringo go home.”

The march, which took place in central Mexico City earlier this month, was an angry local response against a growing global phenomenon: Gentrification, which locals blame on foreigners who have flocked to the capital since the coronavirus pandemic.

Residents of the capital say these so-called ‘digital nomads’ are taking advantage of Mexico’s relatively cheap living standards but pricing out locals in the process.

Making matters worse: a flood of Airbnbs have overtaken the metropolis’ most desirable, central neighborhoods (more than 26,000 listings according to the Inside Airbnb advocacy group), replacing longtime residents with tourists and short-term renters.

It is a trend that’s been echoed around the world, in cites like Barcelona, Genoa and Lisbon, where tourist apartments have proliferated, turning long-term residents into a rarity and causing anger among locals who have seen their communities eroded.

The protest prompted a sharp rebuke from the country’s president, Claudia Sheinbaum. “The xenophobic displays at this demonstration must be condemned,” she said during a daily news conference on Monday. “No matter how legitimate the demand, in this case gentrification, we can’t just say ‘Out!’ to any nationality in our country.”

But many Mexicans were sympathetic to the marchers’ anger. Watching the protest play out on social media from his mother’s home in the nearby city of Puebla, where he was forced to move after being priced out of Mexico City, Daniel Benavides says all he could think was: “Hell yeah!”

A 35-year-old film editor, Benavides moved to the Roma Sur neighborhood in central Mexico City in 2016. Unlike the already trendy Roma Norte and Condesa, Roma Sur still felt like a quiet neighborhood, without the hip bars, restaurants and Airbnbs that had flooded other areas. It was also affordable.

But slowly, things started to change. There was already one Starbucks – then another one appeared, followed by the American fast food restaurant Popeyes. Then came the quaint cafes and bars that all looked the same.

“They all had little incandescent lightbulbs held up by rope,” he said.

Benavides also started to notice an influx of foreigners, mostly Americans.

Soon, the rent for his apartment started to go up. First the landlord increased the apartment’s monthly rent by 3000 pesos (£118) from one year to the next. Then he started increasing it by about 8% annually. Before long it had gone from 15,500 to 20,500 pesos per month (£613 to £810).

Such an increase is relatively modest, particularly by Mexico City standards. Yahir Zavaleta, 40, was living in Roma Norte in 2012, when it was still filled with locally owned businesses and cafes. When his contract came up for renewal in 2014, the rental company wanted to nearly double the rent. Zavaleta and his roommate decided to leave.

Cecilia Portillo, a 30-year-old designer, has lived in Condesa for three years. Recently, she told her landlady that she was moving out, but that a friend was ready to take her place.

“The rent is going to go up by 50%,” said the landlady, according to Portillo, who has also watched a flood of foreigners arrive in her building. “We’ve seen that people are willing to pay that much.”

‘Housing construction has practically stopped’

Such dramatic price rises, particularly in desirable, pedestrian-friendly neighborhoods, are common in Mexico City. A study published by the National Academy of Sciences in 2024 found that, over a 20 year period, average housing prices in the Mexican capital had quadrupled, without considering inflation. In the swanky neighborhood of Polanco, prices increased eightfold between 2000 and 2018.

Yet the study’s authors cautioned that “the influx of digital nomads, which significantly increased during the Covid-19 pandemic, does not appear to significantly impact the dynamics of housing access” noting that it “may be too early to observe the full impact of these newcomers”.

Instead, the study suggested that “displacement and gentrification predominantly originate from government policies and politics.” According to Mexico’s national statistics agency, Mexico City had the lowest rate of new housing built between 2010 and 2020 of any state in the country.

“Housing construction has practically stopped completely in the last seven years,” said Adrián Acevedo, an urban planner and housing specialist. “If there is no housing, then the purchasing power of those few people [who can afford to live in desirable areas], whether it be a foreigner or an upper-class Mexican, will obviously push up the price of the few homes that are available.”

The lack of new housing, and the resulting surge in prices, leaves many lower-income residents with nowhere to go: According to state figures, 23,000 families leave Mexico per year.

In 2022, Benavides’ landlord announced that he had sold the apartment to a French woman: Benavides and his roommates would have to move out. He managed to find a shabby place nearby for 14,500 (£574) a month where he lived for a year. But then the landlord said they were increasing the monthly rent by 500 pesos, and Benavides also found himself without a job.

Benavides decided to move out but suddenly found that rental prices in his neighborhood had skyrocketed up to 25, 35, 40 even 100,000 pesos a month. His old place now seemed like a bargain. With no job prospects and rents unaffordable, Benavides decided to leave Mexico City and move back in with his mother.

“I pushed the emergency eject button,” he said woefully, adding that, particularly as a gay man, he still misses the capital. “It’s a beacon of hope – a place you can be free.”

9 hours ago

6

9 hours ago

6