Before the elections next year, Sweden’s conservative government has been eager to avoid accusations of racism or xenophobia. So it’s unfortunate that it keeps being plagued by scandals involving both.

The Swedish investigative magazine Expo revealed earlier this month that a minister in the governing coalition, whom it did not name, had a close family member active in violent far-right and neo-Nazi groups. The family member had, Expo claimed, participated in activities with a far-right network classified as a terrorist group by the US.

For almost two weeks the minister’s name swirled around social media, but all the major news outlets in Sweden refused to publish it, claiming they were protecting the identity of a minor who had not chosen a life in the public eye.

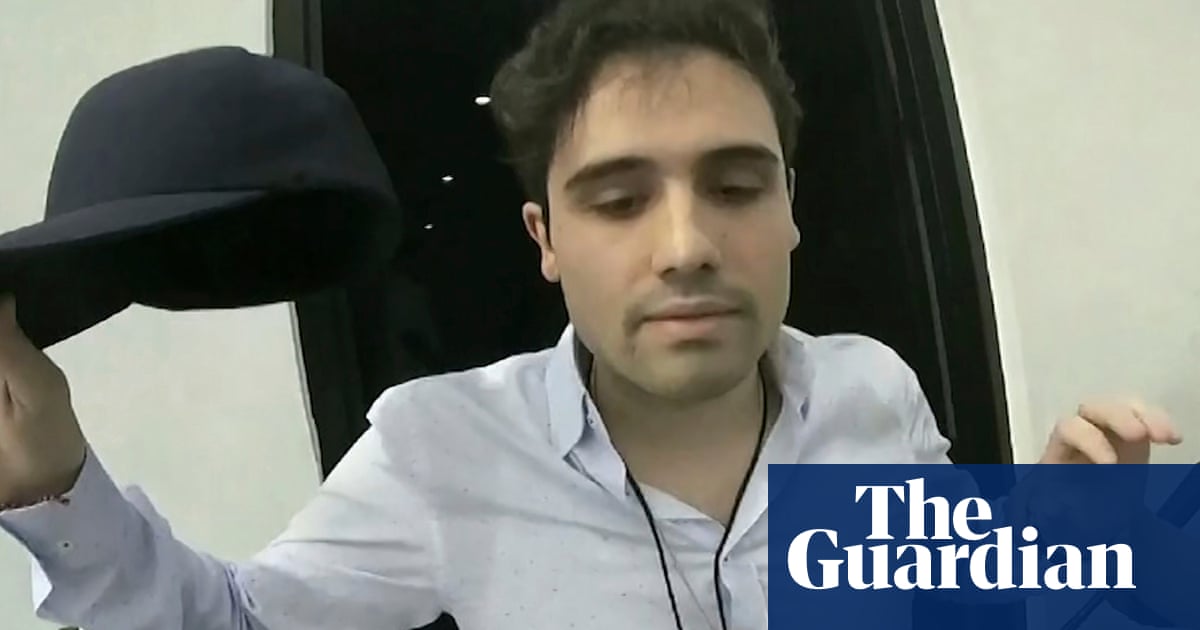

This week the migration minister, Johan Forssell, was finally outed after being called to a hearing in the Riksdag, the Swedish parliament, to answer questions about the scandal – and his teenage son. Eventually he showed up for an interview with Sweden’s national news channel, TV4, in which he said he was “shocked and horrified” by the discovery.

The revelation that the scandal involved Forssell is particularly remarkable, since he has built a reputation on claims that parental responsibility is the only real way to prevent crime. He has also suggested parents should be held legally accountable for the crimes of their children.

While Forssell’s son is not suspected of any crime, he is alleged to have attended in-person meetings with at least two neo-Nazi groups. In one picture published by the magazine, he appears to make a Nazi salute. In an internal chat, the son wrote: “We must get rid of the imported violence” and “it’s time for Europeans to fight back!”, according to Expo.

Awkwardly for Forssell, an MP for the Moderate party led by the prime minister, Ulf Kristersson, he has generally advocated for the most radical shift towards punitive policies in Swedish criminal justice in decades, including harsher punishment for minors.

And in social media posts, Forssell has claimed that the leftwing opposition is in denial about the role of “parental responsibility as a method for crime prevention”. The best way to prevent criminality, he has insisted, is “attentive parents who give their children love and set clear boundaries”. Now the minister wants us to accept that he was clueless that his own child was reportedly active online in neo-Nazi groups, let alone implicated in a violent extremist group with international ties.

Despite the potential risks for Sweden’s national security, Forssell’s party colleagues repeatedly downplayed the scandal. The justice minister, Gunnar Strömmer, simply ignored a question about it, saying he didn’t have an opinion on the issue. A leading Stockholm conservative in the Moderate party, Iréne Svenonius, claimed that the real scandal was that news media reported it at all; it was a “new low”, she said. Another Moderate party MP made light of the story, saying, falsely, that this was just a teenager “posting some memes”.

Ebba Busch, the deputy prime minister, said it was a “sign of strength” for Forssell to “voluntarily make this information public”. But this was the opposite of what actually happened: Forssell and his party colleagues had frantically tried to hide the story, hoping he would be able to remain anonymous.

A local newspaper, Västerbottens-Kuriren, published Forssell’s name in an editorial, but officials in the Moderate party called not just the publisher but also the individual writer to complain. Such explicit intervention is highly controversial in a country where the government is supposed to respect the independence of the press.

Despite Forssell’s long public record of blaming parents for the sins of their children, he took no direct responsibility when finally confronted in the TV interview. Instead, he seemed keen to shift the blame from parents to online platforms, asking: “What is social media doing to our children?” While his own social media accounts have countless negative posts about migrants, the minister casts himself as a passive victim of circumstances. “Sometimes, things go wrong,” he shrugged.

Forssell says he has no intention of resigning. But the timing of this scandal is inconvenient to say the least for Sweden’s conservatives, whose governing coalition is backed by the far-right Sweden Democrats.

For many years, as they pursued harsh immigration policies and tough-sounding rhetoric, xenophobic statements bounced off nationalist politicians in terms of political support. But rightwing parties are now falling significantly behind in national polls. As a voting bloc they are almost 10 points behind the centre-left opposition and they have lost most of their support among young voters.

The governing parties and their allies seem to realise that accusations of xenophobia can be an electoral liability. In June, the anti-immigration Sweden Democrats, which have roots in neo-Nazism, released an internal report about their past, and party leaders apologised to Swedish Jews. This was a transparent effort to convey a more tolerant, mainstream image before the election, when they hope to become a formal part of government. Jimmie Åkesson, the party leader, has said he will only prop up a governing coalition if he can be prime minister.

His attempt to clean up the party’s image is already in trouble, however. When Mahmoud Khalfi, the chair of the Islamic Association, suggested the Sweden Democrats should also apologise to the country’s Muslim population, an influential voice in the Sweden Democrats, the MP Richard Jomshof, launched a vicious attack on Khalfi and Islam, which he called a “hateful ideology”. Khalfi should be “thrown out of Sweden, head first”, Jomshof said.

A government that claims to take concerns over crime, safety and national security seriously while ignoring far-right extremism will struggle with credibility. Sweden has a long tradition of refusing to face up to its racism – past and present. But racism could still decide the next election.

-

Martin Gelin writes for the Swedish newspaper Dagens Nyheter

8 hours ago

6

8 hours ago

6