“Rachel, bad news,” the text message read. “They’re disconnecting the loom tomorrow.”

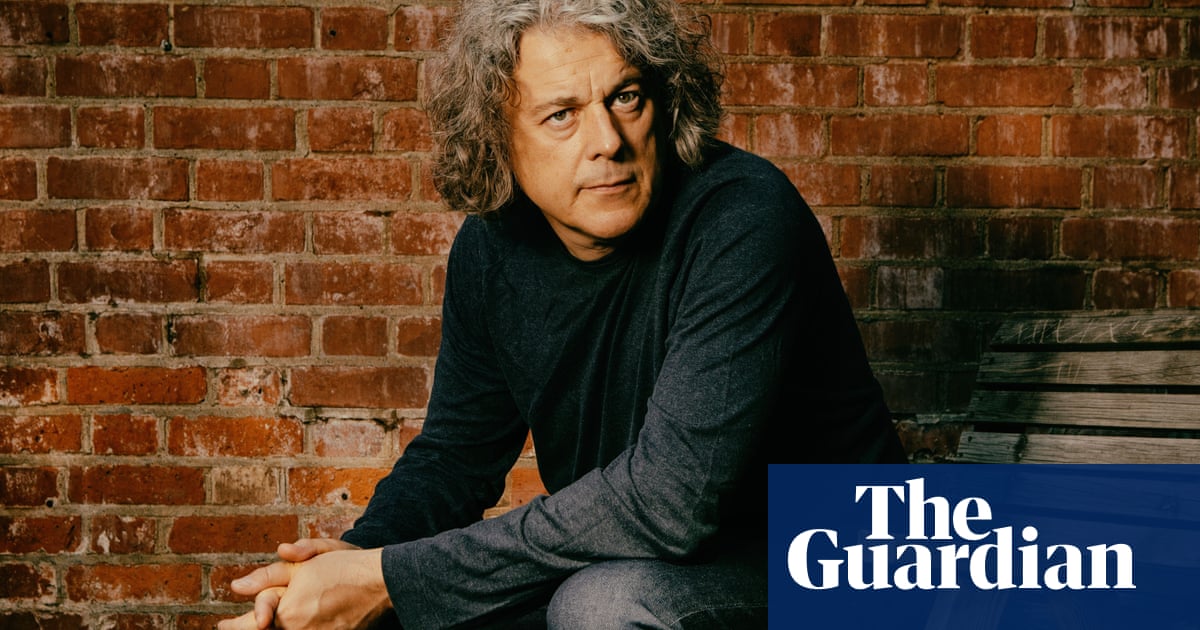

Rachel Halton still doesn’t know who made the decision, in October 2022, to summarily decommission the $160,000 Jacquard loom that had been a cornerstone of RMIT’s renowned weaving and textile design courses for 20 years.

Nearly 3 metres high and weighing more than half a tonne, the loom was an intricate machine of polished wood, steel, compressed air and mechatronics: simultaneously a grand monument to the golden age of the textile industry and a modern tool for weaving strands of yarn into intricate fabrics. Halton knew she couldn’t let it end up in landfill.

“It was my day off and I got up, jumped out of bed and just went down there,” Halton says.

The loom was the only one of its kind in the southern hemisphere, and one of only a handful in the world, bought for the university’s Brunswick campus in the early 2000s, soon after Halton started teaching there. It “elevated what you could do as an artist”, she says. Students enrolled just to have access to it. International artists visited especially to weave on it. It became integral to Halton’s creative practice.

When she arrived at campus that October morning, ready to “chain myself to that tree”, the only other person there was the man coming to decommission it.

“He disconnected it in front of me,” Halton says. “It felt like taking a family member off life support.”

Others felt the same. Word spread that the loom was headed for the skip and a ramshackle collective of weavers, teachers, students and alumni hashed out a plan to save it. They paid a sympathetic technician a case of beer to disassemble it safely, hired a trailer from a service station to transport it and squeezed the whole thing into a former student’s lounge room while they tried to find it a more permanent home.

One member of that collective, a textile artist, Daisy Watt, says the episode felt like “a perfect snapshot of the state of everything” about the way higher education treats fine arts and crafts: where valuable tools and increasingly rare skills are condemned by, as Halton says, “a decision at the end of a spreadsheet”, while community groups and guilds with scant resources do their best to salvage the remnants.

The warp and the weft

The loom’s clunky name belies its significance. Traditional Jacquard looms used punch cards – slips of cardboard with rows of holes, an early form of code – to guide the lifting and lowering of vertical (warp) threads, as fabric is assembled, thread by thread, across the horizontal (weft). This ARM AG CH-3507 loom could be operated by computer or by hand, enabling complete control of every thread, making the design possibilities endless.

Watt has “a very special affinity” with the loom. It isn’t just the time she spent working on it at RMIT, or that it sat in her home for months after it was rescued. She’s also been using her coding skills – self-taught – to update its electronics. It’s as though technology is lapping back on itself, given that Jacquard punch cards inspired the basis of modern computing.

“We normally think of craft in isolation from technology but it’s just this gorgeous, messy thing,” Watt says. “A piece of effective craft technology based on making something beautiful.”

At the time the loom was bought, textile design at RMIT was taught as a stream within a diploma of arts – a course that “people would relocate their whole lives for”, according to a teacher, Lucy Adam.

after newsletter promotion

In 2008 RMIT replaced the diploma with a certificate four training package – part of a broader, contested, national reconstruction of vocational education. This dispensed with a traditional curriculum and focused instead on job-oriented “units of competency” determined by industry and subject to strict oversight.

Federal and state governments claimed the reforms were necessary to streamline qualifications and weed out subpar training providers. Teachers and trade unionists argued they would diminish education and result in systematic de-skilling, whittling down what the labour theorist Harry Braverman called “conscious and masterful labour” to the performance of “simple and ignorant tasks”.

The testimonies of textile design teachers at RMIT suggest that, despite their best efforts otherwise, this is exactly what occurred.

The course became “extremely dry and lowest common denominator”, Adam says. Resources were throttled and student contact hours cut by more than half. Despite the drawcard of the loom, there was no longer time to properly teach students to use it. Halton incorporated it into students’ work where she could, doing the setup, pack-up and maintenance herself.

Adam, whose masters thesis interrogated the impact of the changes to vocational education, says that for trades that are simultaneously technical crafts and creative arts – textile design, ceramics, cookery, metalsmithing, woodworking and others – a checklist of competencies is “not really the point”.

“It’s a really old-school rote way of teaching, unless you’re an incredibly skilled teacher and can work around the blandness of it,” she says.

An artist and teacher, John Brooks, also rues the narrowness of the course structures. For example, one unit’s assessment requirements include describing the process of turning a computer on and off. “So much energy is spent on compliance that the actual core skills we’re teaching are collateral damage,” he says.

Adam once had a student who described the training package as akin to “filling out a visa application over and over again”. “That just made me really sad,” she says. “Where is the mastery? Where is that deep skill?”

It’s a decline not restricted to Tafe. Ella*, a third-year fine arts student at the University of Tasmania, tells Guardian Australia that there are no classes there beyond first year in 3D mediums including ceramics, which is her focus, or furniture, sculpture or time-based media. There are no art history classes either.

“It’s really affecting how developed students’ knowledge is of the contemporary arts scene,” Ella says. Her lecturers try to adapt the courses as much as they can to “freshen it up”, she says – but students desperately need a better technical and theoretical foundation.

Prof Lisa Fletcher, from the University of Tasmania’s arts faculty, says the university understands the importance of the arts, strives to provide “a strong and sustainable offering” for students, and is keen to to hear feedback as the department prepares for a regular review of its fine arts degree.

Crafting the future

The loom is now in a loading dock in Ballarat, an incubator space for which the rescue collective pays peppercorn rent. The city has pledged to maintain and nurture rare and endangered crafts. Some have nearly been lost: leadlighting, for example, was an almost-extinct trade in Australia until a small group of artists revived it, lobbying hard for years to bring it back into the Tafe system and establishing a course at Melbourne Polytechnic. But it is an exception to the rule.

Watt and the other weavers hope the loom will eventually be accessible for people to work, teach and create on again. As Brooks says, the less these skills are practised, the fewer places there are to learn them, “the more chance we have of losing them”.

A spokesperson for RMIT says the university decommissioned the loom because it needed upgrading, and that it was obliged to give students access to “reliable, modern equipment” that would prepare them for their entrance to the workforce. Meanwhile, the space the loom inhabited is now occupied by a military-funded textiles project. The rooms require a security clearance to enter. At the end of last year, RMIT closed enrolments for its certificate four in textile design, after the state government ended subsidies for the course.

But there is a glimmer of hope. Adam didn’t give up. She proposed a new diploma, which has just been approved. And she’s not the only person at the university trying to maintain space for her craft, even as that space keeps shrinking. At the time of writing, the university was about to take delivery of a new piece of equipment: smaller, less sophisticated but still a $100,000 computer-controlled Jacquard loom.

* Name has been changed

3 hours ago

2

3 hours ago

2